Are Cumbrians Spanish?

The history taught in British classrooms says Cumbrians were the pathetic survivors of an Anglo-Saxon massacre. But new research reveals their origins were far sunnier…

Medics at the University of Complutense in Madrid took DNA samples from more than 5,600 people in 19 countries. The results strongly suggest that the inhabitants of the north-west corner of England are the descendants of prehistoric people who migrated from Spain after the last ice age.

It means that the official story about the origins of Cumbrian people needs to be completely rewritten. Before explaining in full what the Iberian medics found in their huge investigation, let’s recap a little.

The traditional version of British history portrays the people of the so-called Celtic Fringe as essentially weak, marginal and unimportant. The term Celtic Fringe was invented in 1890 by the Tory Prime Minister Lord Salisbury as he called for a reduction in the number of MPs representing it.

He wrote: “The great defect of our present representation is that the Celtic edges of the country on both islands are represented enormously out of proportion to the rest of the Anglo-Saxon population.”

Salisbury’s contempt was based on a widely-believed but false version of Britain’s past.

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries it was accepted that the Anglo-Saxons invaded Britain in huge numbers in or around 450 AD. The incomers are supposed to have massacred almost all the Celts who originally inhabited the island.

The pathetic few who survived the bloodshed (including the Cumbrians) were driven to the extreme edges of the country, or so the story went. They were allowed to scratch a living on unpromising land no one else wanted. This tale seemed to confirm two things that appealed to the self-image of the ruling class.

Firstly, it suggested that because the Celts were practically all exterminated, British veins now run with the undiluted blood of tough, no-nonsense Germanic tribes. This is supposed to explain why we had what it takes to build an Empire.

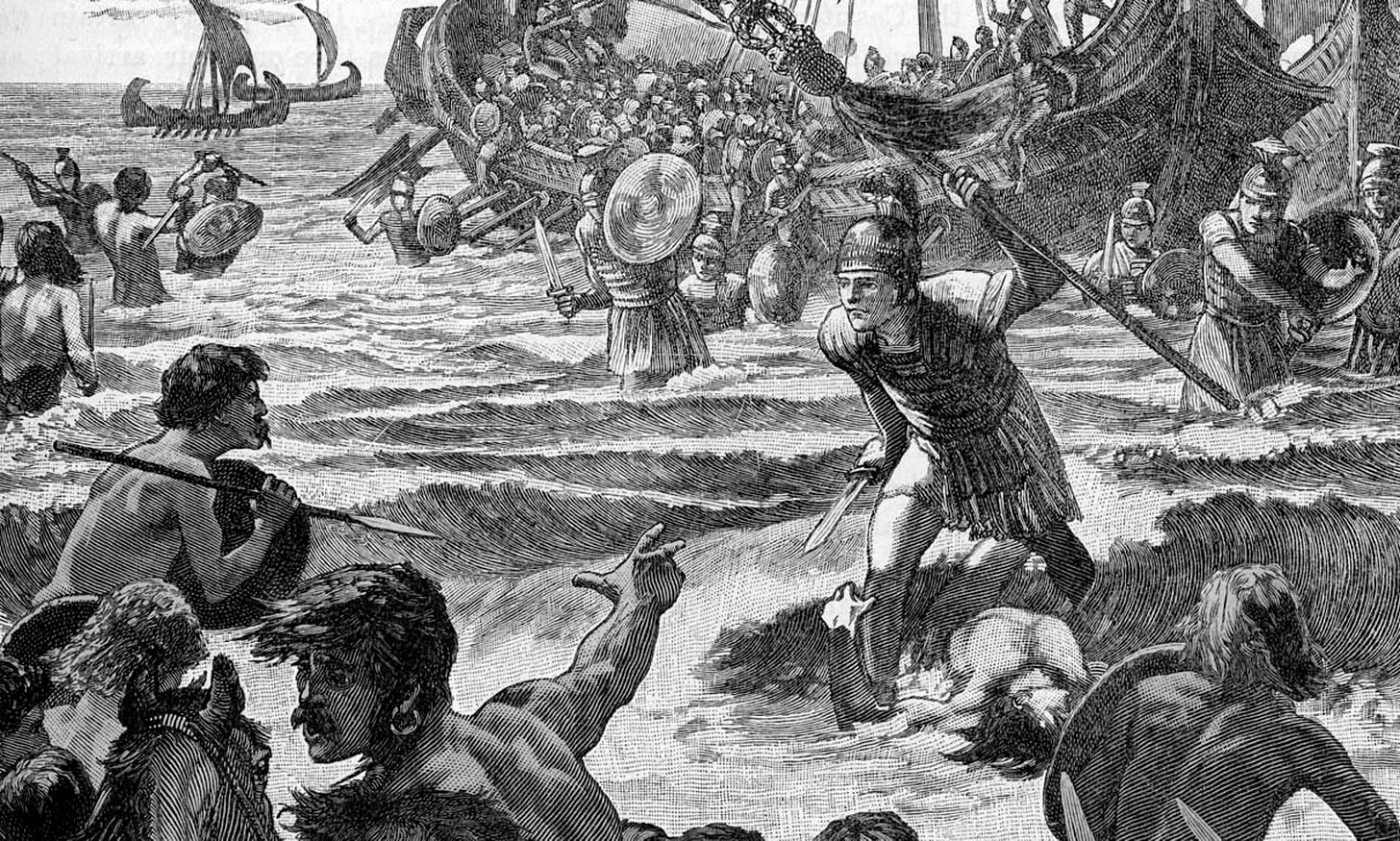

One Victorian historian, Edward Augustus Freeman rejoiced in the assumption that the British were really resilient Germans. He said people should “reverence” the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle “next after your Bibles and Homer (because it) tells us that the first Teutonic Kingdoms in Britain began in the year 449.”

And, secondly, it seemed to confirm Salisbury’s view that the people of the Celtic Fringe are inferior and less deserving of political power.

This tale, which is still very influential among traditionalists, has come under attack by a dissident group of academics over the past few years. They are led by Oxford Archaeology Professor Barry Cunliffe.

He produced DNA research suggesting 68 per cent of Brits are descendants of the original Celtic hunter-gatherers who arrived in Britain after the ice age. He was backed by geneticist Stephen Oppenheimer whose research suggests Anglo-Saxons contributed just 5 per cent to the English gene pool.

These two men argue that, far from being driven west after some mythical slaughter, there is no archaeological or documentary evidence of a mass invasion by Anglo-Saxons and certainly no massacre.

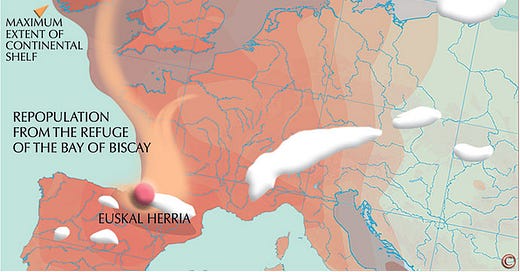

The Cunliffe camp argues that, instead, the Cumbrian Celts migrated north from Spain, Portugal and Southern France after the ice age. They followed the relatively shallow waters of the continental shelf. They shared a culture and language with the people spread all along what he called the Atlantic Facade: the Irish, Welsh, Orkney Islanders, Bretons, Galicians, Basques, Portuguese, Cumbrians and the Cornish.

Cunliffe argues that these migrating Iberians used Celtic as a “lingua franca” rather as English is used as a medium of commerce today.

This view came under withering fire from the traditionalists. If true, it would increase the importance of Celts in Britain’s history that they believe should be diminished. They launched a ferocious backlash to defend the centrality of the Anglo-Saxons who they believe were the exclusive founders British law, religion, Parliament and monarchy.

One leading traditionalist, Professor of Archaeology at Leicester University, Simon James, took to claiming the Celts “never existed” and that they were “invented” by an 18th Century linguist called Edward Lhuyd. He was the man who first identified that the people of Brittany, Cornwall, Ireland, Isle of Man, Scotland, Wales, and, until the 13th Century, Cumbria, spoke mutually comprehensible dialects of the Celtic language, a tongue rather like contemporary Welsh.

James strongly implied that the word Celt was a fiction invented for political reasons. It was a ploy to criticise the English suppression of regional identities, he said. We should simply stop using the term and the whole issue will vanish, James argued.

Critics add that genes do not dictate your ethnic identity, anyway. You can call yourself British without having any European DNA in your body, so genetic evidence may not be conclusive. Even so, the science is so clear that it has dealt a serious blow to the long-cherished “Anglo-Saxon nation” idea.

Now the traditional camp faces a new setback at the hands of a high-powered group of doctors based at the School of Medicine in the University of Complutense in Madrid, Spain. It is one of the oldest and most prestigious academic institutions in Europe.

They decided to test whether the claims of Cunliffe and his allies stood up. It was an extremely large-scale investigation.

They took blood samples from 5,676 people in 19 countries. They came from a selection of Atlantic-facing countries as well as others such as from Japan, Switzerland, Austria in Central Europe and Finland to provide a clear comparison.

The analysis focused particularly on the frequency of the so-called R1b Y male chromosome.

HLA genes are used to match bone marrow recipients with their donors. So, they offer a very precise way of establishing someone’s genetic identity.

The doctors reported their findings in a paper entitled: “HLA Genes in Atlantic Celtic Populations: Are Celts Iberians?” It revealed the HLA readings were low in the non-Facade countries. But they “reached the maximum frequency in North Spain, Brittany, Wales, England, Scotland and Ireland.”

They add: “This suggests an ancestry relationship between populations inhabiting the Atlantic Europe facade.”

The report concluded: “The origin of the Celts is the Iberian Peninsula and not Central Europe.”

Now, this is very interesting because Linguist John Koch claims to have found potential proof of an Iberian origin for the Celts. He found rune-like inscriptions on around a hundred ancient stone tablets or stelae, mainly gravestones, in south western Portugal.

He believes they were written in the world’s earliest Celtic language, Tartessian, using the Phoenician alphabet.

The stelae date back to 900 BC - 200 years before the Hallstatt culture reached its peak in Austria. Hallstatt, according to the traditional view, is supposed to be the cultural centre of Celtdom.

One telling discovery is that the opening line on one Tartessian stelae mentions “Lugos”. This is the same Celtic god that Carlisle (Luguvalium) was dedicated to.

If confirmed, this is a remarkable link between Carlisle and the Portuguese port city of Tartessos 2,000 miles to the south. It is also adds strength to the Atlantic Facade thesis. If Koch is right, his findings mean Celtic culture and language was born in Iberia, spread to places like Cumbria and then to Central Europe, not the other way around.

A growing number of archaeologists believe the Koch discoveries indicate that Celtic was spoken in Iberia before it reached Britain and other parts of the facade before it ended up in the rest of Europe.

The Tartessian hypothesis is still controversial to some academics. Tatanya Mikhailova of the Institute of Linguistics at Russian Academy of Science, Moscow, is particularly sceptical, dismissing his interpretation as “biased” and “far-fetched”.

But Professor Alice Roberts, author of The Celts: Search for a Civilisation, is less sceptical. She believes the Tartessian evidence indicates the conventional story that the Celts invaded Britain from Central Europe: “isn’t just creaking; it’s broken.”

So, are the Cumbrians Spanish? It is beginning to look like they might be.

This is a piece is based on themes in a new book called Secrets of the Lost Kingdom. You can buy the book at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, at the Moon & Sixpence cafe in Cockermouth and Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, and Sam Read in Grasmere.

You can also order by post instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/secrets-of-the-lost-kingdom