Why National Trust puts saving aristocrats before the Cumbrian countryside

A Lake District vicar created Europe's biggest membership body to stop industry destroying rural beauty. But it grew phenomenally in a direction he never intended.

In the spring of 1893, a flagpole appeared on a beautiful, wooded island in the middle of Grasmere, sending Canon Hardwicke Drummond Rawnsley’s blood to boiling point.

The barbarian responsible for this intrusion into the bucolic scene was a pinkly prosperous solicitor from the coal-shipping port of Hartlepool, John Thomas Belk, who also had advanced plans for building projects next to Dove Cottage.

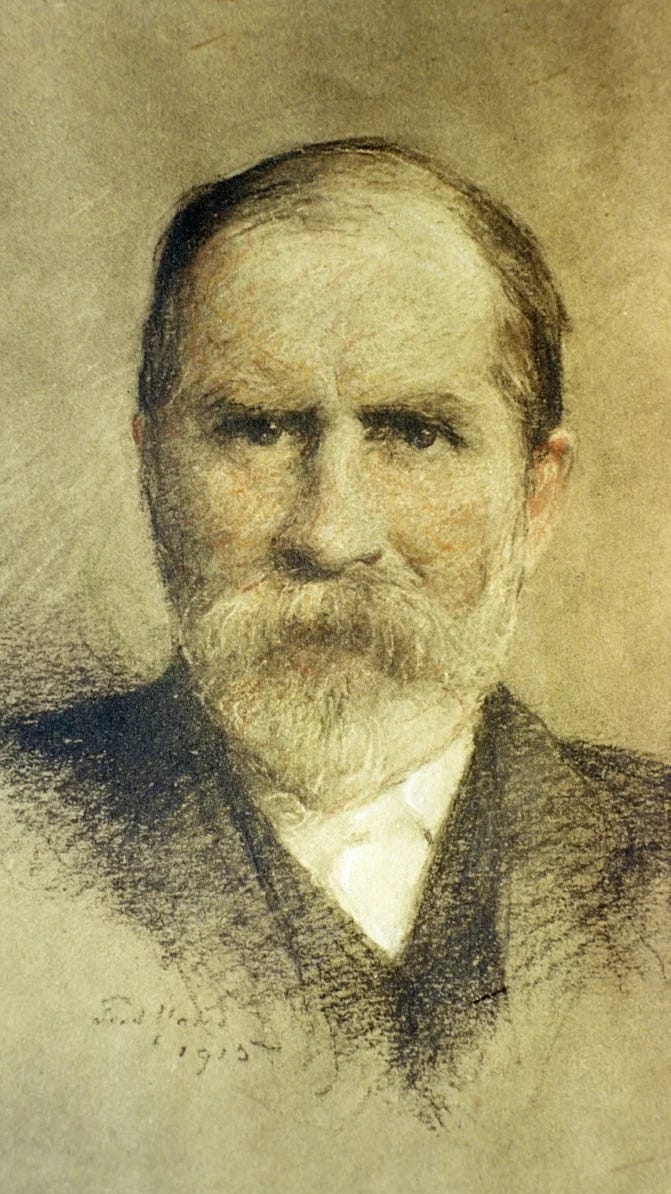

After one of Rawnsley’s most officious letters failed to get the mast pulled down the rebuff spurred the volcanically energetic Anglican priest, poet, and philanthropist into action. Two years later, he converted his Lake District Defence Society into the mighty National Trust with the aim of buying places of historic interest and natural beauty for the benefit of the nation.

Yet Rawnsley’s baby was to grow phenomenally in the opposite direction to the one he intended. Today the National Trust is struggling to live down its reputation for its historic bias towards preserving stately homes and the aristocrats who live in them, rather than the original mission of protecting historic places or chunks of beautiful countryside.

This is happening when England’s 34 areas of outstanding natural beauty are being gobbled up by development 129 per cent faster compared to 2012, according to the Campaign for Rural England.

Yet the vast preponderance of the trust’s resources goes towards preserving houses and providing a generous financial prop to the upper classes that continue to live in them. This stems from the Government’s policy of allowing hard-up aristocrats to hand over their historic houses to the Trust in return for being let off paying millions in tax. They are permitted to remain in residence while the Trust picks up almost every bill. Commentators such as Paula Weideger, author of a critical history of the Trust, "Guilding the Acorn", have dubbed this system as “housing benefit for aristocrats.”

Meanwhile, State benefits to poor people have fallen dramatically. For example, the real value of unemployment benefit has halved since 1971 to just ten per cent of average earnings, according to the House of Commons research unit.

At the same time, valuable intrinsic features of landscapes including heathland, broadleaf woodland and woodland features, lowland meadows, mosslands, hedgerows and hedge banks, tree lines, and traditional stone walls are vanishing in Cumbria, according to the county council.

Commentators have dubbed this system as “housing benefit for aristocrats.”

Today, the National Trust’s mission is very popular. It has 5.6 million members who seem relatively happy with the concentration on upper-class property. It owns over 500 historic houses, castles, ancient monuments, gardens, parks, and nature reserves including nine lighthouses, 56 villages, 39 pubs and a gold mine along with 600,000 acres of land in beautiful places. This amounts to 1.5 per cent of the total landmass of Britain and it includes a quarter of the Lake District.

Political commentators ask how the biggest conservation body in Europe can have remained so unrepresentative? Activist George Monbiot noted in a blog entitled “Whose Nation, Whose Trust?” that unless the Trust took steps to ensure it reflected and belonged to the whole nation: “Large numbers of the urban unemployed, of the young and of ethnic minorities will continue to feel that they do not belong there.”

The Trust's reverence for aristocracy reached a peak when in 2015 the Palladian mansion, Clandon Park, near Guildford was reduced to a shell by fire. Flying in the face of its own mission statement which says that its role is “to protect Britain's glorious buildings” the Trust opted not to protect but to fabricate from scratch a meticulously researched pastiche of the house at a cost of £30 million in which virtually every element is fake.

Erecting facsimiles of buildings is not the Trust’s job. Even its owner Rupert Onslow, the 8th Earl of Onslow, condemned this piece of fantasy conservation as "wasteful."

The seeds of this bias towards aristocratic property were sown at the beginning. Rawnsley was inspired as a young man by the charismatic Slade art professor, architectural critic, watercolourist and social thinker John Ruskin, a polymath who became quite possibly the 19th Century’s single most influential man. Rawnsley absorbed Ruskin’s peculiar conservative-revolutionary ideas. Ruskin’s idealism and naïveté were born out of the fact that he did not have to earn a living or engage with the grubby compromises of everyday life. That was because he lived on a vast inheritance left by his father’s Domecq sherry company.

He rejected modernity, despised capitalism, and argued that industrialisation and free markets destroyed people’s lives and wrecked the landscape. His criticisms met a receptive audience after the British economy hit a severe downturn in 1873. The first signs emerged then that the vigorous German and US economies were overtaking Britain’s. The public mood switched from euphoria over the country’s reputation as the workshop of the world to pessimism as people started to count up the cost of human and environmental degradation they had paid in exchange for a modest prosperity.

Ruskin picked up this theme when he wrote a series of ninety-six open letters to the working classes in the 1870s that he called Fors Clavigera. They fiercely attacked private enterprise and argued that the economy should be run on moral lines, without exploiting of workers for profit.

On one level his thinking was radical, and his arguments spread around the world, influencing the establishment of trade unions, Clement Attlee’s Labour party, the nonviolent activism of Mahatma Gandhi and Leo Tolstoy’s sympathy for the peasants. However, what some failed to grasp is that the revolution Ruskin envisaged would be profoundly reactionary and consist of a dramatic shift backwards in a medieval direction.

Sure, he urged a better deal for the working classes, but he didn’t want them to have more power. Thus, John Ruskin bequeathed a divided legacy. As John K Walton wrote in “Constructing Cultural Tourism” there are “Left Ruskinians” and “Right Ruskinians” according to whether his admirers placed the emphasis on Ruskin’s ethical socialism or his self-description as a “violent Tory of the old school.”

Rampant industrialisation, the expansion of cities such as Manchester, and the ever-growing railways that imported unrefined tourists into unspoilt landscapes would soon overwhelm Britain, Ruskin said.

In 1849, he wrote in The Lamp of Memory that the British had an obligation to preserve buildings as a kind of national heritage: “We have no right whatever to touch them. They are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them, and partly to all the generations of mankind who are to follow us.” The countryside deserved the same protection, he went on: “God has lent us the earth for our life; it is a great entail (family inheritance).”

When framed in these Biblical terms, any eruption of modernity into the landscape is an offence against the Almighty. And that means Mr Belk, as a confederate of Middlesbrough’s steel barons and Hartlepool’s shipping magnates, was a harbinger of moral and cultural chaos when he put up his flagpole.

Ruskin was in prime position to influence Hardwicke Rawnsley’s defence of the Lake District as, in 1871, he made his home at Brantwood on the shores of Coniston Water. According to Hardwicke’s granddaughter Rosalind it was “John Ruskin, whose ideas and philosophy were to shape the whole concept of the nascent National Trust."

In 1877 Hardwicke Rawnsley became a fully-fledged priest and, with blinding good luck, was offered the living at tranquil Low Wray, a stone’s throw from the shore of Windermere.

Hardwicke used regularly to walk the six miles over the fells to Ruskin’s house at Coniston where he received the advice of “The Master” on his various campaigns to prevent the despoliation of the fragile environment of the Lakes.

The Canon set up the Lake District Defence Society as a watchdog after after a Bill permitting a rail line from Honister down the beautiful Borrowdale valley to Braithwaite almost slipped through Parliament unnoticed. In a furious appeal published in The Spectator in February 1883, the vicar warned “Borrowdale and Derwentwater will no longer be the quiet resting-ground for weary men” because the “shrieks” of shunting engines and the flying bottles of “beer drinking excursionists” would soon shatter the peace.

On 12 January 1895 Hardwicke set up the National Trust with Olivia Hill and Sir Robert Hunter, a brilliant lawyer and campaigner against ordinary people being shut out of common land by developers. A crucial step into the embrace of aristocrats came when Hardwicke persuaded the conservation-minded Duke of Westminster to put his name on the notepaper and to lend them his house in Mayfair’s Grosvenor Square for a first meeting of “influential people”. Soon, a long list of aristocratic names had signed up as supporters and set to work identifying properties to acquire.

But, again, the Trust was really Ruskin’s idea. The notion first surfaced in 1854 when Ruskin wrote without result to the Society of Antiquaries urging them to create a “Conservation Fund” to preserve medieval buildings. The idea resurfaced in 1894 when Ruskin made Hardwicke a member of his Guild. Thanking him, the vicar wrote: “This will stimulate us and encourage us... and since example is better than precept, I send you an account of our National Trust, for which again St. George is answerable...”

When Hill died in 1912, and Hunter the following year the Trust was still overwhelmingly concerned with the countryside. It had 712 members, an annual income of £1,677, and owned just 13,200 acres of land, making the Trust roughly the size of a single landed estate. What changed the picture was the rise of the Right Ruskinians that took place just before the First World War.

In 1909 the Liberal Government faced two threats - the need to finance the building of Dreadnought battleships to deter German naval ambitions and fear of being replaced by the surging Labour Party. To meet these difficulties the then Chancellor Lloyd George introduced his so called "People's Budget" in 1909. He slapped huge new taxes on unearned income from the sale of land, imposed higher death duties on the wealthy, and a supertax on incomes above £3,000. His onslaught on aristocratic pockets provoked a power struggle that ended with the House of Lords having its powers severely curtailed.

Soaring taxes meant the lesser aristocracy found they could no longer afford the upkeep of their historic houses and by 1918 one quarter of British land was up for sale.

Though the son of an ironmaster, Conservative Premier Stanley Baldwin, who became Prime Minister in 1923, affected to be deeply attached to the British countryside.

This was partly in an attempt to portray the Tories as the repository of English decency in contrast to the allegedly corrupt Welsh Wizard Lloyd George. If anything, the cult of Ruskinian values became even more pronounced after World War One than before. The Baldwinite sentiments were fully shared by failed Conservative Parliamentary candidate, John Bailey, who was chairman of the National Trust for nine years from 1922.

He recruited three important men to the Trust’s board: the historian GM Trevelyan, a personal friend of Baldwin; Ronald Norman, a future BBC Director General and brother of Montagu, the Governor of the Bank of England, who took charge of the Trust’s finance committee; and Oliver Brett, heir to the Viscountcy of Esher.

Trevelyan saw the Trust as a repository of “spiritual values” an antidote to the “base materialism” of the age and a “bulwark” against "barbarism” .

Even the self-confessed snob and Trust grandee Harold Nicholson commented, “I am rather worried that this committee which actually decides whether we take a house is composed entirely of peers.”

But John Bailey saw no problem with “a class of cultivated an intelligent people” deciding what was good for everyone one else, insisting the Trust should put preservation before public access. As Monbiot put it: “They set about protecting what they deemed to be the treasures of the nation not for the people, but from the people.”

…..

This is an extract from a chapter from our gripping new book entitled “People of The Sacred Valley” which tells the histories of remarkable individuals who lived along the banks of the Derwent River in Cumbria.

You can pick up a copy from The Moon and Sixpence Coffee House or the New Bookshop, both on Main Street, Cockermouth. It is also available at Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Or you can buy it instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/details/p5921133_21146598.aspx