Why England's first king failed to conquer Cumbria

Athelstan, Alfred the Great's grandson, achieved a massive expansion of his empire in a short time - but the proud land of the Cumbrians proved too big a mouthful

This is a full chapter from “Secrets of the Lost Kingdom” - exclusively for paid subscribers.

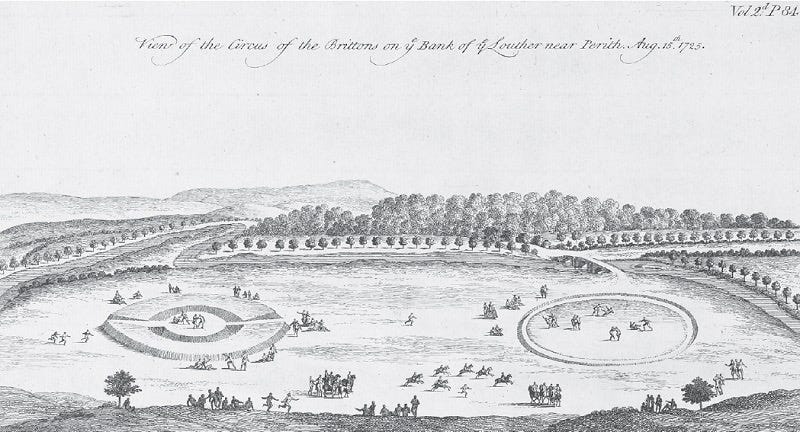

Why did five kings meet, a thousand years ago, at Eamont Bridge? To the modern eye, the grassy mound near Penrith, squashed between the unsleeping horror of the M6 motorway and an accident black spot, seems an unlikely place for a royal conference. But on 12 July 927 AD, when Athelstan, the Anglo-Saxon king of southern England, presided over this high-level meeting, it was a savage and intimidating place.

To the visitors Cumbria would have seemed a bleak stretch of countryside surrounded by a wilderness of steep-sided valleys and fast-flowing streams and that Athelstan had deliberately selected it to put his guests at the maximum disadvantage. It was also, Athelstan reckoned, a magical spot. Eamont Bridge lay at the “pen rhyd” (chief ford) on what had been the main north-south and east-west routes serving the west side of the island since prehistoric times. Any army invading the north would have to come that way. In Anglo-Saxon folklore, a crossroads was a location between worlds where angels, demons, gods and spirits could be contacted and supernatural events could take place.

With his slender, muscular body trained to the peak of martial fitness and his beautiful blonde hair curled in shoulder length tresses, the ambitious thirty-three-year-old warrior-king Athelstan was a majestic and unnerving sight surrounded as he was by an enormous retinue of soldiers. Devout, bookish and shrewd, Athelstan had inherited much of his grandfather Alfred the Great’s political and military talent - and he was all too aware of the precarious nature of power. Athelstan was extremely conscious of the importance and persuasive force of magnificence in kingship. He was the first English king to have himself portrayed wearing a crown as a potent symbol of his divine authority, rather than merely a helmet indicating military supremacy. Yet he felt enormous pressure to emulate the warrior success of his father Edward the Elder, who had begun the reconquest of the Danelaw, the area of the north and east of England grabbed half a century before by the hated Vikings.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.