Why do we let greedy metal detectorists sell off our history?

A gaping legal loophole let two men sell “unparalleled” Crosby Garrett Roman helmet privately for £2.3 million, destroying vital historical knowledge - and it could happen again

In May 2010, a metal detectorist in his 20s dug up one of the greatest Roman masterpieces ever found in Cumbria, the Crosby Garrett cavalry helmet, in 67 fragments.

It is an exceptionally important, rare and precious artefact, the first of its type to be found in Britain dating from the turbulent 3rdcentury of the Roman occupation. Historians are desperate for more evidence about this obscure period, when the country was politically unstable, usurpers launched bids for Imperial power and the Picts, Caledonians and Saxons threatened to overturn the regime.

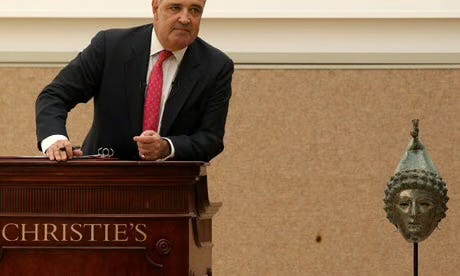

But the finder and the landowner rebuffed all requests from leading experts for the unique artefact to be given a full scientific examination and formal archaeological conservation. Instead, it was superglued together and stiffened with resin by an employee of Christie’s auctioneers. The two men were made very wealthy by the sale. But in the process, irreplaceable information about the helmet’s burial, its construction, who owned it and how it was used were lost and destroyed.

British Museum archaeologist Roger Bland described the rush to achieve a commercial sale as “the worst possible outcome” and “a great loss” to history because it disappeared into private ownership without adequate scientific study or sufficient public access.

The headpiece consists of two components, the bowl or helmet itself and a mask resembling a human face.

Its features are of an incredible, chilling, androgynous, almost feminine beauty.

The face plate shows an idealised, clean-shaven youth with stylised curly hair. The helmet wears a Phrygian cap of the type that adorned Homer’s Paris, the mythical hero who started the Trojan war. The cap is topped with a winged griffin, a symbol of courage associated with gladiators. The disturbingly expressionless face was originally coated with tin which would have shone mirror-like against the gold of the brass helmet.

The visor was originally attached to the headpiece by means of a hinge, the iron pin of which has not survived. The helmet would have been held on the rider’s head with a leather strap attached from the neck to decorated rivets on either side of the helmet, below the ear. The decorated rivets and the pierced eyes are of a type used in the 3rd century.

It is very likely that the helmet was owned by a military commander. Only the highest-ranking soldiers with the best horsemanship were allowed to wear helmets like this during sporting competitions known as hippika gymnasia. These were flamboyant displays of military prowess, performed in front of military chiefs and emperors, by elite cavalry units.

Curiously, the manoeuvres were Celtic in origin. The Roman Empire began systematically recruiting locals (non-Italians and provincials) into the Roman army primarily during the second century AD. This shift became widespread under Emperor Hadrian who visited Cumbria in 122 AD.

The British Celts who joined the Roman army practiced a form of mounted warfare using spears, javelins and shields. The gymnasia performances involved complex manoeuvres on horseback and re-enacting legendary battles such as the wars of the Greeks and the Trojans. The Roman author Arrian wrote that the helmets were designed “to attract the attention of onlookers” and they were extremely highly regarded.

Both horse and rider would have been resplendent in lavishly decorated clothes and armour. The riders attached yellow plumes to their helmets that streamed in the breeze as their horses moved forward. Unlike standard combat gear, with which equestrian soldiers were issued and required to return at the end of their period of service, cavalry sports equipment was commissioned and paid for by individual soldiers.

The Crosby Garrett helmet is an example of top-quality craftsmanship. Such a helmet would have been the prize possession of senior auxiliary cavalryman who served at a high level in one of the crack Roman regiments stationed in the frontier region of northern Britain.

Ralph Jackson, Senior Curator of Romano-British Collections at the British Museum said the helmet is “…an immensely interesting and outstandingly important find ... Its face mask is both extremely finely wrought and chillingly striking, but it is as an ensemble that the helmet is so exceptional and, in its specifics, unparalleled. It is a find of the greatest national (and, indeed, international) significance."

Academics disagree over whether such helmets could have been used in combat.The wearer’s breathing would have been limited with air coming through two small nose holes. His peripheral vision through the eye holes would also have been restricted, which could have proved fatal in hand-to-hand combat.

Even so, there are clues suggesting they were not only deployed on the parade ground. The distance between the eye holes in the Crosby Garrett helmet is greater than the average modern adult. The helmets were deliberately designed to test the mettle of chosen cavalrymen.

The former student found the helmet in 33 large metal segments and 34 smaller fragments in a remote farmer’s field. The finder initially did not realise he had unearthed a Roman artefact, thinking the curly hair was reminiscent of a Victorian ornament. He eventually identified it as Roman by consulting auction catalogues, searching the Internet and getting advice from Christie’s.

Rather than agreeing to a delay to let academic experts examine the find, the detectorist authorised Christie’s auctioneers to fix the bits together in a 240-hour reconstruction operation that was focused appealing to a buyer. A saleroom employee used cyanoacrylate (superglue) and resin to reinforce the helmet internally, then sanded smooth and textured the inner surfaces.

Christie’s made a silicon mould of the helmet’s hair and used it to cast a metal replacement for one-and-a-half missing curls. A hole in the chin about 2.5 inches wide was filled with resin, then gilded with silver leaf and distressed to match the rest of the face. Cracks were closed either by hand or by using pliers and small clamps covered in masking tape. The rest of the helmet was worked over with hammers and dollies (small, flat platforms wheels to help in moving the artefact around). Traces of cracks and splits can still be seen on the finished article, and lightly cleaned surfaces retain some earth.

But this reassembly was not done in an academic manner and the methods used obscured and destroyed irreplaceable archaeological evidence which will never be recovered. Christie’s billed the helmet as “an extraordinary example of Roman metalwork at its zenith” when in fact it is an imaginative, not a scientific, recreation.

Micro-remains disappeared. For example, the helmet would have been worn with soft padding inside. But it was not possible to look scientifically for residue of this, nor for traces of the glue that secured it.

This disaster happened because of a gaping loophole in the law. Because the helmet is made of non-precious metal rather than gold or silver it was at that time not classified as “treasure”. If it had been, the helmet would have been put in the care of a museum and the finder would have got a substantial cash reward.

Sally Worrell from the Government-run Portable Antiquities Scheme, a body set up in 1997 to try and stop precious artefacts being dug up and illegally sold for profit, said: “Had archaeological conservation taken place then we might have learned more of the way in which it was buried, and among other things, features such as impressions of textile fabrics which can survive in metal corrosion products might have been identified. It was clearly a great shame that it was not possible to undertake such formal archaeological conservation…”

Once Christie’s got their hands on the helmet, they also ignored increasingly desperate appeals from nationally-respected experts and politicians pleading for a delay in the auction to allow a scientific restoration to take place. Instead, the detectorist and the local farmer on whose land it was found, auctioned the irreplaceable item off to anonymous private British owner on October 7, 2010, for £2.3 million.

Handing this unparalleled item over to the whims of private ownership means that opportunities for research, education, and public display have now been severely limited. Vital archaeological, scientific, and cultural information that could have deepened understanding of Roman Britain have been permanently lost.

The sale price was well out of reach of a rival bidder, Carlisle’s Tullie House museum, even though that institution did well in raising £1.7 million against the clock - the timetable set by the Christie’s sale - from donors including the National Lottery and overseas philanthropists including the J Paul Getty Trust.

Critics are still outraged about the gap in the British legislation which prevented the helmet being properly conserved and made available for view in a public collection. The hurry to get it into the saleroom prevented scientists analysing subtle features like textile impressions that can be left in the corrosion on the helmet’s surface.

Microscopic clues which could have told an immense amount about how it was wrapped, stored or displayed in ancient times have been clumsily and permanently erased.

So, what is being done to stop precious historical artefacts ending up on the commercial market? In 2023, Ministers made a partial attempt to close the legal loophole by reforming the Treasure Act. The new version of the law declares that an object made of base metal would in future count as treasure if it is deemed “significant.” The legislation now says such an object would be significant if: “it provides an exceptional insight into an aspect of national or regional history, archaeology or culture.”

Under the new rules, the Crosby Garrett helmet could not have been sold privately. But the revised law still fails to force finders to report discoveries promptly. Stone, ceramic or indeed wooden artefacts are still not covered. The rule change will still not stop private sales of nationally important finds that do not fall within the new definition.

Metal detectorists have contributed a lot to archaeology. They have uncovered significant artefacts, such as the Winchester Hoard, Iron Age coins, Bronze Age hoards, and Anglo-Saxon grave goods, which have led to the identification of previously unknown sites and enriched our understanding of historical periods. But there is widespread concern about illicit detecting, especially on protected or scheduled sites, often done at night. This results in the loss of crucial evidence and heritage. Successful prosecutions are rare.

This is an extract from a forthcoming book. There are already five books in the series of Hidden Cumbrian Histories. You can buy them at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Buy online here: www.fletcherchristianbooks.com

TO READ THE WHOLE ARTICLE AND MORE, SIGN UP TO A PAID SUBSCRIPTION

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.