Why Cumbrians risked death seeking fortunes in India

They braved a perilous sea voyage, ignored a one in three chance of dying and worked decades for a scandalous company hoping to become a super-rich Nabob

Why did hundreds of Cumbrian men and women endure a dangerous 7,000-mile sea journey to take a job in India when one in three died of disease within two years of getting there?

What possessed the county’s best educated youths to travel six months in a noisy, smelly boat laden with animals around the notorious Cape of Good Hope where seven ships were lost in a single storm in 1722?

Why put up with being crammed into tiny canvas-walled cabins with the risk of catching dysentery, scurvy, and typhus due to primitive hole-in-the-hull sanitation?

And was the ordeal worth it when they arrived at Bombay, Madras or Calcutta bored out of their minds and physically weakened? All they could look forward to being was a toiler for the notoriously corrupt and ruthless East India Company for five or ten years without a holiday.

Nabobs: some Cumbrians who became richer than their wildest dreams toiling for notorious East India Company

Who would volunteer to work twelve hours a day in 100-degree heat as a lowly “writer” (junior clerk), tax collector or court gofer?

What is the allure of being forced to live in Company residences like monasteries with entertainment options limited to the alcoholic lure of the whites-only club and the gambling tables? The author C.P. Hull, who wrote the “Anglo-Indian’s Vade Mecum”, a guidebook for Europeans in India, warned new arrivals to beware:

“every facility is afforded the thoughtless and self-indulgent for getting into debt in India… and no habit is more apt to grow, than one of gratifying every wish as it occurs.”

Junior staff faced working 30 years before they could enjoy the prestige diversions laid on for the Company’s elite, such as theatrical performances and tiger-hunts.

Even if the youngsters survived the sea voyage they risked being caught up in fighting as the Company’s 250,000-strong army relentlessly tried to extend the Company’s territory.

After that, the main threat to life and limb came from the tropical climate, inadequate sewage systems and ignorant doctors whose incompetence led to high mortality rates from cholera, malaria, smallpox and leprosy.

Death was ever-present as Andrew Hudleston, who became a high official in Malabar, South-West India, wrote from Calicut to his aunt at Whitehaven in 1819:

“Many people apparently in good health, while walking along the road, have been seized with a giddiness in the head, fallen down, vomited & died in the short space of half an hour.”

Out of 421 Cumbrians who landed jobs with the East India Company between 1680 and 1829, some 133 died in post and never returned to Cumbria. This was twice the death rate in the British Isles.

So, in exchange for a paltry starting salary of £40-£50 a year in 1860 (£6,800 now) rookie recruits to the Company faced a life of hardship, monotony, and danger.

A fascinating analysis of why they did go has been pieced together by sociologist Katherine Saville-Smith. She collected biographical fragments left behind by the 421 Cumbrian men and 23 Cumbrian women employed by the East India Company over a period of 150 years.

Her book, “Provincial Society and Empire: the Cumbrian Counties and the East Indies, 1680–1829” suggests the young Cumbrians took on the challenge because the Company offered opportunities for social and economic advancement that were increasingly difficult to achieve within Cumbria itself.

The main price they paid was a severely restricted average life expectancy. On average, Company recruits lived a little under thirty-nine years.

The East India Company was originally set up in 1600 by Elizabeth I to obtain spices from the East. But it evolved into one of the most powerful corporate entities the world has ever seen. The Company grew to become a state within a state. With thousands of employees, it acquired a scope that extended far beyond commerce.

The Company became a military and political superpower and an economic engine that reversed history. The most profitable commodities it traded in were pepper, cloves, nutmeg, cinnamon, and mace, cotton textiles such as calico, chintz, muslin, and dungaree, indigo dye, saltpetre for gunpowder production, silk, porcelain, gold, silver, coffee, sugar, carpets, salt, ivory, raw cotton yarn, and manufactured goods, and, most controversially, Indian opium was exported to China in exchange for tea despite being illegal under Chinese law.

But the company had some problems. It faced persistent charges that through violence, exploitation, and suppression of native people it was flouting principles of moral equality and dignity.

Critics deplored its monopolistic practices, rampant corruption, its paying of bribes and kickbacks. In the most horrific incident, the Company was widely criticised for exacerbating the Bengal famine of 1770, which killed up to 10 million people, after Company managers hoarded grain and then offered minimal direct relief to victims.

So why, in the face of this criticism, did the Cumbrian youth seek careers with the company?

The answer, Katherine found, was that many of them saw Company life as a path to adventure and upward mobility in a new, exotic world leading to potentially immense wealth. There is little evidence that any of them were motivated by nationalist sentiments or a desire to aid imperial expansion.

Many Cumbrian families expressed reluctance to allow their young to embroil themselves in what seemed to be a dangerous enterprise. Parents often pleaded with their offspring, usually their second sons, up until the last minute, urging them to choose a domestic career instead.

For example, Thomas Pattinson’s mother Mary wrote to her son at the point of departure in 1805: “I longed to know what your sentiments now are in regard to going abroad, for if you had in the least disliked it you should not have gone.”

But, as Katherine Saville-Smith put it: “adventurous youths were frequently more enthusiastic about the East Indies than their families”.

When George Fleming wrote to his father, the landowner Sir Daniel Fleming of Rydal, from Oxford proposing to seek an East Indies career he acknowledged that the stipend he could expect initially as an East Indies chaplain was small. But, he added, he had hope of acquiring a “goodly sum” as he progressed up the corporate layer. He told his father: “There are so many advantages, as have very well rewarded my predecessors’ journeys, particularly the last who brought £3,000 home with him.”

Two days’ later George’s cousin the future MP Henry Brougham, also at Oxford, wrote to Daniel, his godfather, in a panic:

“Yesterday, and not before, I was informed of my Cous. George’s intention to go to the East-Indies … I look upon it to be one of the most unaccountable projects that was ever Set a foot … ’Tis great odds but he looses his life in the voyage … [but] there is neither interest, improvement or reputation to be got by it.”

Believing George’s chances of making a fortune were only a thousand to one, Sir Daniel wrote back to his son refusing his consent “fearing that I shall never see you more.” There was no need to go to India because “you are not (God be praysed) in a Desperate condition”, he wrote.

William Wordsworth’s brother John saw his employment with the East India Company as a pathway to personal wealth and to supporting his family. (He was determined to privately trade in rice and illegal opium between India and China and to return with tea).

He served as a captain of the Earl of Abergavenny, one of the largest trading ships of its time. In 1800, John wrote to Mary Hutchinson, soon to be his brother’s wife, that he had been told he would be rich within ten years. But his first voyage to China produced disastrous losses. He wrote: “‘Oh! I have thought of you and nothing but you; if ever of myself and my bad success it was only on your account.”

Then, tragedy struck John on February 5, 1805, when the Abergavenny sank off Weymouth Bay in Dorset with the loss of 263 lives. John dutifully went down with his ship.

So, candidates for the initially poorly-paid but potentially lucrative roles with the Company, knew the risks. But they were enchanted by examples of writers with connections who performed well and advanced rapidly up the management chain.

Relatively junior officials could legitimately earn large commissions when handling big cargoes or, less ethically, by creating a local monopoly in certain commodities.

Some junior employees went further and accepted bribes from local rulers, merchants, and zamindars (landowners) in exchange for favourable treatment or reduced taxes.

Others strayed deeply into the dark side, using their inside knowledge to engage in plundering or illicit trade, which could generate huge fortunes quickly, though these activities were risky and often illegal practices such as dealing illegally in opium.

Ultimately, the young recruits dreamed of becoming a “nabob”, a conspicuously rich individual. (The word nabob comes from the Urdu term nawāb or high ranking official).

When these get-rich-quick merchants returned to Britain with large fortunes they were mocked (and envied) for their flashy, vulgar, nouveau riche behaviour. Nabobs often bought large estates where they put on aristocratic airs.

One example is Keswick-born Edward Stephenson, a former East India Company official, who bought an estate near his home town that he called The Howrahs, after Howrah, a city near Calcutta.

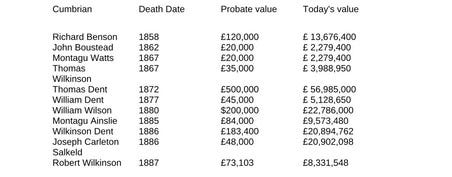

Another former executive with the Company, Cumbrian Thomas Dent, born in 1796 in Crosby Ravensworth, rose to become a senior partner and in 1824 set up in his own right as a private merchant. The greatest nabob to be produced by Cumbria, he left a phenomenal fortune of £500,000 (worth £56 million today) in his will when he died in 1872.

This is an extract from a forthcoming book. There are already five books in the series of Hidden Cumbrian Histories. You can buy them at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Buy online here: www.fletcherchristianbooks.com

TO READ THE WHOLE ARTICLE AND MORE, SIGN UP TO A PAID SUBSCRIPTION

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.