Who made Chernobyl more disastrous for Cumbria? Whitehall did

Three weeks after Chernobyl nuclear explosion in Ukraine, bossy but ignorant Government officials descended on Cumbria insisting there was nothing to worry about. They could not have been more wrong

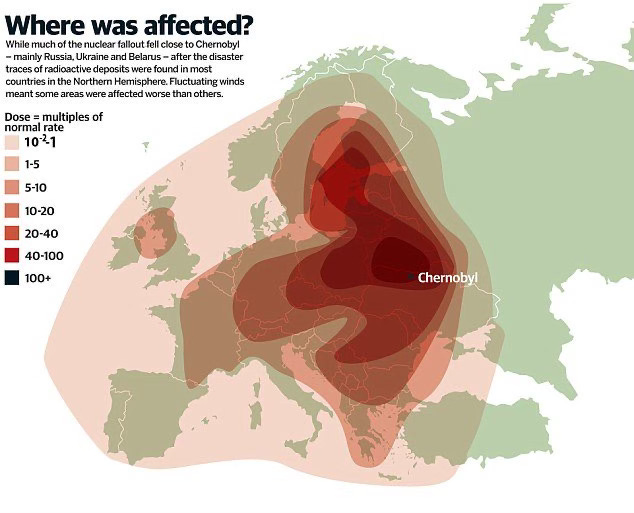

When the shoddily designed Chernobyl nuclear reactor exploded in 1986, the blast sent a huge cloud of poisonous particles nearly a mile up into the sky.

Over the next 26 days, a quirk in the weather steered part of the noxious mass towards the west coast of Britain. Then a thunderstorm broke, washing a colossal load of radioactivity onto the Lake District fells.

For weeks after the contaminated downpour, British ministers attempted to dismiss its significance. They claimed the tainted dust would be swept away by rain within “ten days”, that lamb meat in the shops was safe and no precautions were necessary.

Then, suddenly, they reversed course and imposed severe restrictions on livestock sales that were still in force a quarter of a century later.

The disaster cost the taxpayer £55 million in compensation payments for irradiated sheep that had to be sold off at a loss and triggered years of contested and unresolved claims by hard-up sheep farmers.

Even though radiation censors showed the worst pollution was found next door to Cumbria’s notorious Sellafield nuclear reprocessing plant, Ministers still insisted the vast majority of the radiation had come from far away Chernobyl.

Deeply sceptical farmers felt vindicated two years later. An independent survey confirmed that 50% of the caesium particles had indeed come from Sellafield and associated nuclear bomb tests. It was clear much of what Ministry scientists had claimed was untrue.

Newspapers lambasted the “shambolic” official handling of the crisis. A powerful committee of MPs complained that the scientific advice that Ministry scientists had rigidly imposed on farmers regularly turned out to be wrong or out of date.

Its members criticised officials for ignoring the local knowledge of farmers. “The ill-co-ordinated nature of the information and advice aroused rather than calmed public anxiety, uncertainty and distrust…and led to years of upheaval for affected communities,” the MPs declared.

Social scientist Bryan Wynne is one of many historians who have criticised southern elites for failing to consult or respect the expertise and practical knowledge of local sheep farmers during the Chernobyl crisis. This fuelled distrust, resentment, and a sense of alienation.

The treatment handed out to Cumbrians is a 1,000-year old tradition. Historians have frequently noted how arrogant dictats from the south sparked northern discontent - for example over Henry VIII’s Reformation in 1537, the radical Puritan Parliament in the Civil War of 1642-51 and the hefty pro-Brexit vote in 2016.

On 26 April 1986, a botched safety test blew the 1,000-ton roof off the Chernobyl reactor. Like an erupting volcano, the stricken plant spewed a cloud of radioactive contamination nearly a mile into the air.

The poisonous vapour drifted generally west for three weeks. Prevailing winds steered the noxious substance around the 6,000-foot Carpathian Mountains. It was still heavily laden with deadly caesium-137 particles when, after a journey of 1,500 miles, it arrived over the Lake District peaks on 2 and 3 May.

There, lurking thunderstorms washed a massive dose of radioactive dust onto the Cumbrian fells. It meant that some of Chernobyl’s heaviest contamination dropped, not inside the Soviet Union, but onto Cumbria. About 1.2 inches of rain fell in 24 hours. The downpour meant twenty times as much radiation landed as would have done if the weather had remained dry.

When the rain hit the uneven Cumbrian terrain, it formed rivulets and puddles, swishing the particles around, so the level of radiation could vary enormously within the space of a yard. The Cumbrian hills, especially the southwestern part near Sellafield, received the highest caesium fallout in the UK.

But, in public, Ministers attempted to dismiss the whole thing. On 6 May, the sleek Environment Secretary Kenneth Baker told Parliament that “the effects of the cloud have already been assessed and none represents a risk.” Radioactivity levels, he said, were “nowhere near the levels at which there is any hazard to health in the United Kingdom” and the cloud was moving away.

National Radiological Protection Board boss John Dunster predicted Chernobyl would cause “a few tens” of extra fatal cancers in the UK over the next 50 years. “The whole thing will be over in a week or ten days,” he said. The very same day, however, officials found lamb taken from the Cumbrian fells recorded radiation levels 50 percent greater than the “action level”, the point at which meat sales should be banned.

“The whole thing will be over in a week or ten days,” - National Radiological Protection Board boss John Dunster

The Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food remained deathly quiet. It said nothing significant until four weeks after Kenneth Baker’s initial statement. It took seven weeks for it to hold a press conference. One journalist said: “It was incredible - the silence was deafening.”

When it broke the silence, the Ministry’s tactic was to fudge the issue. On May 30 the department announced that because hill lambs were not yet ready to be sold and their high radiation readings would soon decrease “these levels do not warrant any specific action at present.”

Then, totally without warning, on June 20, Ministers reversed their position. Agriculture Secretary Michael Jopling announced an immediate ban on the movement and the slaughter of sheep in designated parts of Cumbria. Despite this, he still insisted the ban would only last three weeks because radiation levels would soon decline.

“There is no reason for anyone to be concerned about the safety of food in the shops,” Jopling insisted. It was true that “unfinished” Cumbrian lambs had higher levels of caesium than in the rest of the country, but these readings would diminish before the animals were sold, he said.

Jopling’s statement was based on a Ministry theory that new, clean grass would soon grow up to replace radioactive grass.

Grazing lambs would gradually ingest less contamination. Since caesium had a half-life of about 25 days, levels in meat would roughly halve in 21 days, he calculated.

The Minister’s consoling words were soon proved redundant. Levels of caesium did not decline as he predicted. Some lambs began testing at even higher radiation levels than before. On 24 July, Ministers were forced to extend the ban in Cumbria indefinitely. Government officials and nuclear scientists descended on the fells to consult farmers on managing the restrictions and to do research on soil, vegetation, and animal contamination.

At the height of the ban, movements of four million animals on 7,000 UK farms were prohibited. Then, on 30 September 1986, the freeze on Cumbria was reduced to a crescent around the Sellafield plant. The number of Cumbrian farms affected fell from 1,670 to a core of 150.

Within that cordon, hill farmers became desperate. As Lancaster University social scientist Brian Wynne wrote in his seminal analysis of the crisis “Sheepfarming after Chernobyl”, these farmers’ livelihoods depended on “rearing a large crop of lambs each spring and selling them in the late summer and autumn.” Revenue from that sale was their only significant income.

Normally, farmers allowed ewes to produce more lambs than the land could support because the early ones could be sold off in August, releasing grazing for the new ones. But this year the Government ban meant hundreds of thousands of spring lambs could not be sold. Yet new lambs kept being born, so farms became overpopulated and there was soon not enough grass for them all to eat.

Farmers began to worry they’d be ordered to slaughter all contaminated sheep, not just the lambs. This would be a disaster. No mothers meant no lambs the following year too and the total disruption of the rearing process. Traditionally, young Lake District sheep learn from their mothers a strong attachment to a specific area of open hill or fell, known as a “heft”. Slaughtering this year’s animals would threaten financial disaster because of the massive cost of rebuilding flocks.

One farmer said that officials were unable to comprehend this: “They couldn’t understand that you were going to sacrifice next year’s lamb crop as well. They just couldn’t grasp that!”

Yet Ministry scientists remained convinced, despite growing contrary evidence, that radiation levels would soon decline and the ban on sales would be lifted. So, they ordered farmers to hang on to their lambs “a little longer”.

Their confidence was ill-founded. Their optimism was based on a research study they had conducted on alkaline lowland clay soils which indicated that radiation quickly became chemically neutralised. This was a blunder. The scientists had failed to notice that Cumbrian fell topsoils are not clay. They are acidic and the poisonous caesium remained in the roots of the grass and so continued going into the lambs’ bodies.

Meanwhile, the order to “hang on” to lambs was causing consternation. Farmers repeatedly told officials that their prosperity depended on picking exactly the right moment to sell when their spring lambs were in peak condition. They had to monitor prices, pasture conditions, disease buildup and the condition of breeding ewes. Sheep numbers were overwhelming the amount of grazing land. Hanging on to lambs past the optimum moment threatened them with bankruptcy.

On 13 August 1986, officials finally relented. They permitted farmers to sell sheep in contaminated areas as long as they tested below the action level of radiation.

However, blue-painted sheep who had initially failed the test were held back until their contamination readings fell to safe levels. If they passed when re-monitored they were marked with apricot or green. The stigma of radiation was such that apricot-green sheep could no longer command top prices, so they were sold at knock-down rates to certain customers in Europe.

Then a kind of madness descended. Ministry officials decided that since the heaviest contamination was on the high fells, they ordered farmers to move sheep to the valleys. If there was not enough grass there, they should feed their animals with straw, they said.

Farmers were flabbergasted. Moving sheep from the fells required a massive cooperative effort by the entire farming community and, for larger farms in bad weather, the operation could take ten days.

One said: “(The experts] don’t understand our way of life. They think you stand at the fell bottom and wave a handkerchief and all the sheep come running. . . . I’ve never heard of a sheep that would even look at straw as fodder. When you hear things like that it makes your hair stand on end. You just wonder, what the hell are these blokes talking about?”

By this point, the Ministry’s insensitive and ignorant authoritarianism had eroded the trust of the farmers. “A deep natural scepticism is induced toward decision-making systems based on a belief in control and certainty,” Wynne wrote.

This is an extract from a forthcoming book. There are already five books in the series of Hidden Cumbrian Histories. You can buy them at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.