What really lies at the bottom of Dunmail Raise

The last king of Cumbria may not be buried under a heap of stones on the A 591. But his story tells us his realm was an independent Celtic kingdom born 1,000 years ago.

For hundreds of years, travellers have been told by that the pile of stones in the middle of the road between Grasmere and Thirlmere marks the grave of Dunmail, the last Cumbrian king.

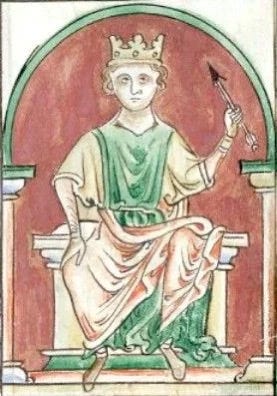

Here, in 945 AD, the brave final member of a long line of British monarchs, whose Celtic name was Dyfnwal ab Owain, was supposedly killed by the Saxon English King Edmund I. Prisoners of war were ordered to pile rocks over his body to create a cairn in tribute.

Until recently professional historians have played down this tale, arguing that is little more than a beautiful myth fancifully elaborated by an early thirteenth century chronicler, Roger of Wendover.

The unromantic truth, they insisted, is that the humdrum heap of stones does not contain Dunmail’s bones. It simply marks the border between the old counties of Westmorland and Cumberland.

It’s all a bit of a let-down. Or is it?

There is another way of looking at this story. The traditional narrative misses the real point. Younger scholars believe the illiterate people of the past preserved real history in folk tales. They say the fable contains more than a kernel of truth.

A careful look at the sources reveals there was indeed a battle in that year between Dunmail and Edmund. It did not necessarily take place at Dunmail Raise.

Dunmail was defeated and although he continued on the throne his status was massively diminished. The victorious Edmund handed the overlordship of Cumbria to his ally Malcolm I, King of the Scots.

Dunmail was not killed – he survived to die on a pilgrimage to Rome thirty years later. So, a piece of whimsical Cumbrian mythology turns out to have more substance than we thought.

Why does it matter? Well, because it casts new light on what everyone knows, whether they were born in Cumbria or have spent any time there – that the place feels distinctly different and separate from the rest of England.

Yet it’s hard to identify precisely why. One thing the tale of Dunmail tells us is that after the Romans left Britain in 410, Cumbria was ruled as a separate kingdom for 535 years, up to the point when Dunmail lost his kingdom. That is not a trivial amount of time. It is at least half as long as the English monarchy claims to have existed.

Even after Dunmail suffered his demotion, Cumbria remained as a recognisable Celtic kingdom, albeit under Scottish influence, for almost another 150 years until well after the Norman Conquest.

The name Cumbria, which many people assume was created by the stroke of a bureaucrat’s pen in 1974, first appeared in an official context more than a thousand years ago in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. This was a collection of annals first commissioned in the late ninth century by King Alfred and written by monks. The chronicle was born at a time when England and Scotland were beginning to emerge as the countries we know today and, as we shall see, the name Cumbria is probably much older than that.

This chapter, and a large part of this book, is devoted to exploring the origin and enduring impact on British culture of this lost kingdom. Cumbria (or Cumberland-Westmorland-Furness as it is called after the local government reorganisation in April 2023) is distinctive because it was the last piece of territory to be added to England. Yes, Cumbria is the newest bit of England and as a result it is the least like the rest of it.

Twenty-six years after William the Conqueror invaded, the proud, independent kingdom of Cumbria was reduced to mere provincial status as a distant outlier of the Anglo-Norman state by the Norman king’s son, Rufus the Red in 1092 AD.

But even after Rufus’s brutal takeover, the records show Cumbria retained its Celtic identity and a profound folk memory of its past greatness. Before the Normans annexed the place, Cumbria had its own separate language, culture, tax system and institutions. The legacy of this can still be felt today.

As the author of the classic A History of Cumberland and Westmorland William Rollinson wrote in 1978: “It has been said that Cumbria is more of a country than a county and there is a degree of truth in this.”

Rollinson attributed the area’s distinctiveness to its trademark beauty, its hostility to innovation, resistance to change and its well-defined borders extending from Deadwater Fell in the north to Walney Island in the south, St Bees Head in the West and Kirkby Stephen in the East. It is an important geographical unit, one that has been remarkably stable and popular for very good reasons.

This ravishingly beautiful, intimidatingly mountainous, remote and occasionally storm-lashed place beloved of poets, painters and thinkers enjoys an astonishingly deep past and it has had a powerful influence on British culture.

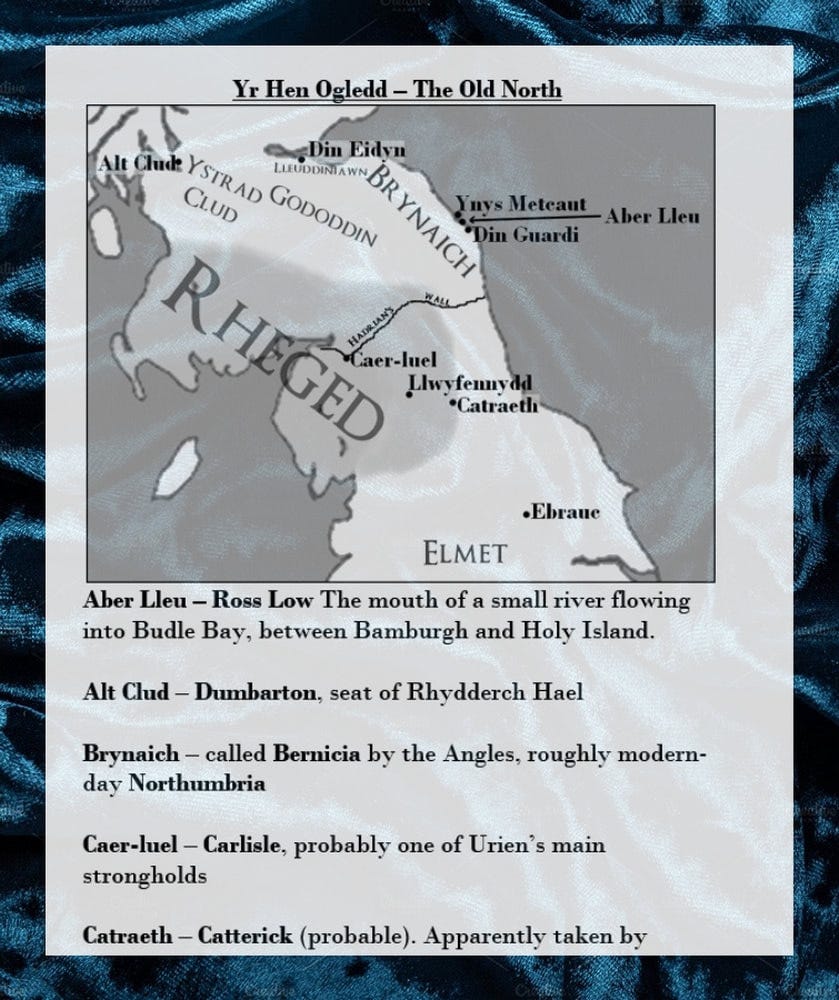

One example of this that I explore in my book, The Lost Kingdom, is the story of the kings of Rheged. This was the kingdom that emerged in the footprint of the Canton Carvetiorum - the Roman administrative area based on Carlisle that covered the area where the Celtic Carvetii tribe lived - once the legions withdrew in 410AD.

King Urien and his son Owain are not mythical but very real figures who ruled Rheged in the sixth century. They won wide fame by inflicting catastrophic defeats on Anglo-Saxon war bands coming over the Pennines from Northumbria.

Urien’s main power-base is thought to have been at Caer-Ligualid (Carlisle) where there are archaeological traces of a pre-Roman Celtic fort and evidence that a community of British Celts lived there well into the 7th century complete with a town council and a working Roman aqueduct.

Rheged reached the summit of its magnificence in the late sixth century. King Urien, then the most famous of all Rheged’s rulers, who was at that time acknowledged as the leading king of all Britain, besieged the Theodric, nicknamed Firebrand, king of Anglo-Saxon Benicia. Theodric’s capital was the forbidding coastal fortress of Bamburgh. The standoff took place on the nearby island of Lindisfarne and lasted three days.

Like other Celtic leaders, Rheged’s kings prided themselves on ferocity in war, modelling their aggression on wolves and lions, wild boars and ravens. They were fond of conspicuous display. They adorned themselves with metalwork and brooches, wore golden torcs and drank from golden vessels. They retained the loyalty of their war bands by rewarding their warriors with captured gold.

But just at the moment Urien believed he was about to inflict final defeat on the Anglo-Saxons, he was assassinated at the behest of a treacherous ally, Morgant Bwlch, who reputedly envied Urien’s power and military skill.

It was a murder that seriously weakened the Celtic cause in the north. Although Urien was probably, as historian Tim Clarkson put it, mainly just “a typical barbarian warlord striving to enhance his wealth and status at the expense of his neighbours” his exploits made him an icon of resistance for the Welsh who were fighting a losing battle against the encroaching Anglo-Saxons.

The bards turned Urien into a character in the legend of King Arthur. He is at first portrayed as an opponent of Arthur becoming king, but after being defeated he becomes Arthur’s staunch ally in the stories. The Lost Kingdom had a powerful influence on British culture.

—-

This is an extract from our new book, Secrets of the Lost Kingdom. You can buy it at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, at the Moon & Sixpence cafe in Cockermouth and Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, and Sam Read in Grasmere.

You can also order by post instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/secrets-of-the-lost-kingdom