What is the real meaning of this 1,000-year-old Viking cross?

Refugees from a 902 AD Irish battle erected enigmatic 15-foot monument in their new home. But exactly what is this bafflingly equivocal work trying to say?

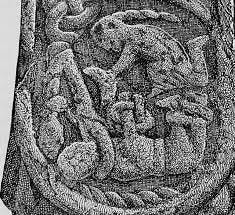

A slender fifteen-foot shaft of ruddy sandstone stands in the middle of a graveyard about two miles from the Cumbrian coast. It is covered with mysterious, some might say crazily interlaced, carvings of men wrestling with giants and demons. When you look at it from a distance, it looks Christian. Get nearer and it looks Pagan. Close up, it looks Christian again. Or does it? It’s weird.

The richly ornamented Gosforth Cross looks oversized as it towers over rows of conventional 18th century gravestones in the grounds of St Mary’s church, as if some ancient gardener had been too liberal with the fertiliser. But its incongruous size is not the only remarkable aspect of this piece of masonry - for one thing it has stood in the same place for 1,200 years and the people who put it there were not actually Christian.

So who created this mysterious monument smothered in pagan imagery, why did they do so and what the heck does it all mean?

These were some of the questions on the minds of two learned Victorian gentlemen who arrived in the churchyard on a dull wet day in 1881, determined to decode what they suspected was the inarticulate speech of the Viking heart.

Dr Charles Arundel Parker, an obstetrician, was with his friend the burly, bearded Reverend William Slater Calverley, vicar of St. Kentigern's Church in Aspatria. They may have seemed unassuming local amateurs to their acquaintances. But through diligent study and painstaking scrutiny they had become extraordinary antiquarians (a grand word meaning someone who studies old things). Their discovery changed the history of Britain. Weeks of pouring rain had softened the lichens that then filled every hollow and divot on surface of the enigmatic shaft.

The haut-bourgeois pair watched as Dr Parker’s coachman climbed a stepladder and gingerly scrubbed the masonry with a wet brush. The first section he uncovered was the triquetra, a symmetrical triangular ornament of three interlaced arcs decorating the head of the cross, a religious symbol adapted from ancient Pagan Celtic images.

Gradually, with each swish of the brush a visual record of one of the greatest cultural transformations in English history emerged from under the mossy camouflage. Depictions were uncovered of obscure Scandinavian sagas and Norse mythology apparently hinting at parallels with the Biblical Apocalypse and Crucifixion of Christ.

This story in stone was soon recognised as one of the greatest works of art of its type in Europe. But what on earth did it all mean? Well, frankly, the interpretation of the equivocal scenes on the four faces of the shaft has provoked a fierce debate that may never end. Sure, the stone monument clearly depicts figures in various scenes from the cycle of Norse myths called Ragnarok. This translates roughly as “twilight of the gods” or Gotterdammerung, the violent destruction of god and man as a prelude to an uncanny regeneration of human life on earth.

This was a very exciting discovery for our two antiquarians. It came only six years after Wagner caused a European sensation with the first performance of his Ring cycle based on the Ragnarok myth. Until Victoria's reign, Vikings were portrayed as purely bloodthirsty and violent. But perceptions were changing. Aided partly by the popular success of the haunting illustrations of Wagner’s libretto by the English book illustrator Arthur Rackham, Vikings were increasingly seen as fine representatives of the old northern virtues of boldness, honour and enterprise at the heart of British nationhood.

A consensus was growing among conservative intellectuals that Viking blood flowed in Victorian Britain’s veins, and that the time had come to celebrate this as an alternative to the “left-wing” rationalism that “caused” the French revolution.

The story of Ragnarok was dear to the almost entirely illiterate Vikings who began to colonise the west coast of Cumbria a thousand years ago. It tells how the world will end in an apocalyptic midwinter battle between the gods that destroys the planet, submerges it under water and how the world will ultimately recover and be repopulated by two human survivors. Our two Victorian antiquaries believed they could see parallels between the Viking imagery appearing on the Gosforth cross and the Christian story of Noah’s flood, Adam and Eve and the Apocalyptic destruction of the world in Revelation, the last book of the Bible.

On closer examination the correlations became more intriguing and ambiguous. One set of images appears to depict the death of Baldr. He is the god of light, joy and purity and also son of the most important Norse god, Odin. His demise perhaps reflects the crucifixion of Christ. The Norse goddess Nanna, who represents joy and devotional love, could parallel Mary Magdalene’s role. Then the cunning and mischievous snake god, Loki, is shown being bound just as Satan was by the Christian God. Hod, the blind Norse god, (another one of Odin’s sons) is shown being tricked by Loki into shooting the mistletoe arrow that slayed the otherwise invulnerable Baldr.

It also shows the battle Odin has with the charred fire giant Surtr, which perhaps echoes how Christ ultimately conquers the Devil. Then at the base of the cross is the mysterious Yggsdrasil, traditionally believed to be an enormous ash tree. In fact, it is more likely the long-living yew, a tree which has the strange ability to regenerate itself from apparently dead roots. This mystic tree’s branches link the nine realms of the cosmos symbolising the cycle of birth, growth, death, and rebirth just like the Biblical Tree of Life.

So, how did this extraordinary artefact get there?

This is merely an extract. You can read the rest of this fascinating piece about England’s first true industry in a new book called Huge & Mighty Forms. You can buy the book at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, at the Moon & Sixpence cafe at Lakeside, Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, and Sam Read in Grasmere.

Or instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/Huge___Mighty/p5921133_20075309.aspx

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.