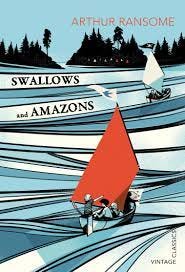

Was Swallows and Amazons author a double-crossing traitor?

Best selling children’s writer Arthur Ransome beguiled the world with his tale of Lake District sailboats. But does the story hide a guilty secret?

Arthur Ransome, author of the great children’s book, Swallows and Amazons, and a friend of Lenin, was suspected by MI6 of being a traitor to his country.

The beloved writer, a life long visitor to Cumbria who owned a house in Low Ludderburn on Cartmell Fell from 1925–35, was one of the greatest journalists of the 20th Century.

He went to Russia at the start of the First World War and married Leon Trotsky's personal secretary Evgenia Petrova Shelepina in December 1917 while covering the Russian Revolution for the now-defunct Daily News. He had such excellent contacts at the Kremlin that British intelligence chiefs employed him to convey messages to and from the Communist leadership. He beat Lenin at chess.

But his relentlessly favourable newspaper reports of the Soviet upheaval and his growing closeness to the leaders of the insurrection convinced Britain’s spy chiefs Ransome had turned into an apologist for Communism. As the husband of an ardently Bolshevik woman, they suspected he was a double agent leaking vital secrets to Britain’s disadvantage.

The accusations horrified and outraged Ransome and when he fled Russia disillusioned by the bloodthirsty turn that the revolution eventually took, he penned his most famous novel as a thinly veiled defence of his actions.

Lenin's revolution, the resulting civil war, famines and the brutal domestic repression that he led against dissidents and scapegoats directly led to the deaths of over eight million citizens of the Russian Empire, many by starvation, torture, or summary execution.

For that reason, Swallows and Amazons is far more than a jolly tale of pre pubescent children messing about in boats. It is in fact is a symbolic defence of his life and values. He offers a repudiation of false accusations of dishonesty and treachery. The story also hints that Ransome regretted wasting his life pursuing journalism and false causes when he could have remained in Britain to care for his estranged daughter.

The book contains a “false flag” incident in which innocent children are wrongly accused of attacking a houseboat with fireworks. The youngest girl character emerges as the heroine of the story when she witnesses a stolen treasure chest being buried. The tale is an imaginative attempt to re-immerse himself in the childhood that he desperately needed to recapture in order to heal the psychic wounds the revolution and his own early life had left him with.

Though dreamy and easily distracted, the young Arthur consumed books voraciously. He could read Robinson Crusoe at four and his proud father gave him a copy of the Protestant parable as a reward. At eight years old he wrote his first story entitled “The Desert Island,” an embryonic Swallows and Amazons.

But Ransome was also given a brutal introduction to a harsh principle of bourgeois English life as a boy aged ten when his father threw him into Lake Windermere and told him to sink or swim.

Cyril, an alpha male type, had the pleasure of seeing his son sink like a stone. Even when the boy saved up his pocket money and secretly taught himself the backstroke at the local public baths his father called him a liar until given proof of his son’s achievement.

Short-sighted and academically undistinguished, Arthur never shook off the trauma of his childhood being terminated early by being sent away to study at Old College, Windermere.

There, the headmaster called him a coward because he was too short sighted to defend himself in the boxing ring. Arthur briefly ran away. Yet when not forced to learn, Arthur picked things up quickly enough. Despite everything, Arthur hero-worshipped his father, a history professor at what became Leeds University, but was conscious he was already failing to achieve the great things that were expected of him.

Then, when Arthur was still a boy, Cyril came to grief unexpectedly. Returning to the family’s holiday home at Higher Nibthwaite in the dark after a nighttime fishing expedition on Coniston, he tripped over an old grindstone. Cyril developed some form of tuberculosis and progressively had to have his leg amputated at the foot, then knee and finally the thigh. He died in 1897, a few days after Arthur had started as a junior at at Rugby school.

As he followed the coffin, Arthur was horrified to discover he felt a mixture of grief - and relief. Arthur bore the imprint of his father in reverse. Where his father was a stern Conservative, Arthur was a Gladstonian Liberal. Where Cyril was a conventional Imperialist, Arthur was a complex, secretive bohemian who championed the underdog. Arthur was particularly fond of the left wing essayist Hazlitt. Yet his father cannot be said to have failed to influence his son. Many of Cyril's traits, such as difficulty in understanding other people's point of view, re-emerged strongly in Arthur's personality.

Cyril introduced Arthur to the Lake District - the great imaginative consolation of Arthur's life, and his main defence against his father's coercive values. Arthur grew to love Coniston, and it became a private rite for him on arrival to run down to the water and dip his hand in, as a greeting.

It was probably in reaction to his father’s Toryism that Arthur grew up with an outlook that allowed him to be intimate friends with the leaders of the Russian Revolution. Ironically, Arthur became a newspaper correspondent almost by accident, driven by the outbreak of war and lack of money. Yet his dream had always been to live tranquilly in the magical Lake District and to become an author.

He wrote to his mother Edith in January 1916: "Some day or other, regardless of the advantages of a settled income, I shall fling my typewriter over the moon, catch it on the other side and with a joyful yell and spend three years pouring out novels."

The Russian Revolution unleashed contradictory feelings in Arthur. He had a strong emotional bond to his bourgeois class. But he felt he had been judged painfully wanting by its standards.

Having abandoned formal education early he felt the Oxbridge crowd looked down on him as ignorant and maladroit. An incorrigible Romanticist, he mistook the band of ruthless cut-throats running the Revolution for Treasure Island pirates or the knights of King Arthur's Round Table.

It is not surprising that his reports idealising the Bolsheviks drew accusations of treachery. And even when Arthur was secretly recruited by MI6 to spy on the Kremlin, Whitehall seethed with suspicions that he was a double agent, betraying secrets to both sides.

This accusation of dishonesty is what drives the plot of the famous book he eventually wrote in retirement, Swallows and Amazons. By writing it he may have sought to cleanse himself after the atrocities of the Russian Revolution that he guiltily realised he had been wrong to defend.

-

This is an extract from our book “Huge & Mighty Forms” which asks the question: why did Cumbria, England’s most thinly populated county, manage to produce so many unique people whose work has changed the world?

You can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop on Main Street, Cockermouth; Moon & Sixpence at Lakeside, Keswick; Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Or you can buy instantly here: www.fletcherchristianbooks.com