Thirlmere not only scarred Cumbria - it was a fraud

Cockermouth's John Grave helped Manchester desecrate a Lake District beauty spot. Then the swindler and his embezzling chief clerk Frederick Heaton milked the scheme for money

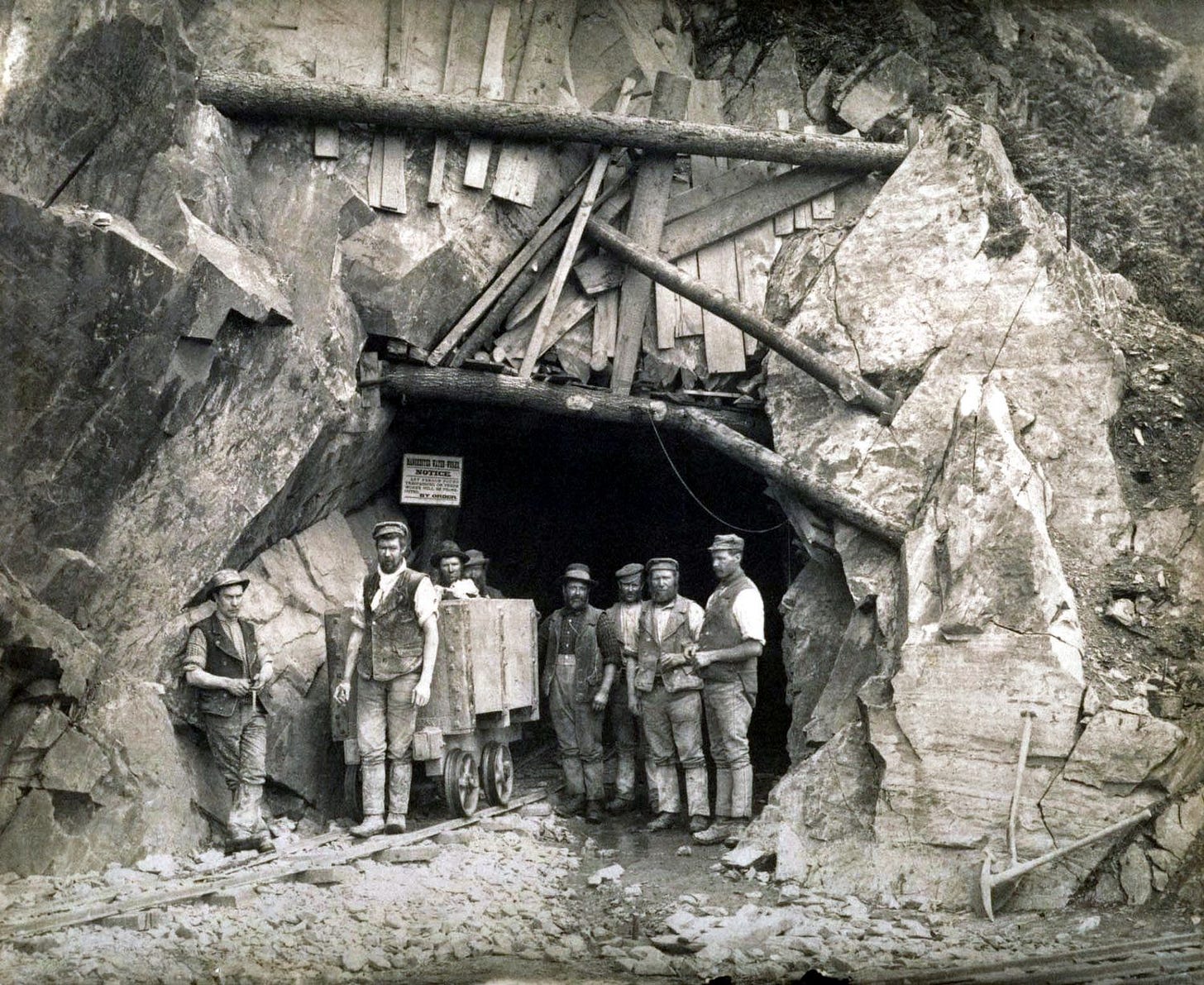

In 1879, the booming cotton capital of Manchester transformed Thirlmere from a pristine beauty spot into a workaday reservoir, pumping millions of gallons of Cumbrian water every year a hundred miles south to the soot-smeared metropolis.

The vast project not only scarred some of the country’s most magnificent countryside it left an ugly mark on the reputation of Britain’s supposedly high-minded civic leaders. The men most closely involved in pushing through the project had more on their minds than averting an industrial crisis and cholera outbreaks - they were intent on lining their own pockets.

After lengthy Commons struggle, Manchester Corporation obtained royal permission to turn the beautiful, remote lake into a water tank for thirsty cotton mills, provoking a chorus of protest from nature lovers in the Lake District Defence Association whom they called “sentimentalists.”

The project raised the water level sixty-four feet, submerged the hamlets of Wythburn and Armboth, destroyed a birch forest, erased a shoreline rich in beauty and folklore and endowed the lake with an artificial-looking muddy skirt during droughts. But was the drip-drip of press reports of official self-indulgence, lavish perks and, ultimately, outright fraud and theft that, for many, most damaged the reputation of the scheme.

The abuses ranged from petty expenses claims, hotel stays, first class rail travel and banquets, to a nine-day ratepayer-funded picnic for scores of councillors.

What capped it all was the revelation that Cockermouth-born Alderman John Grave, the Chairman of Manchester’s Waterworks Committee, who inspired the Thirlmere project in the first place, treated the fund intended to buy land beside Thirlmere, as a source of free loans for his calico printing business.

It was accepted that unpaid members of the council should receive expenses so they were not out of pocket when asked to do official business.

They got a generous allocation of first-class travel and a standard guinea and a half a day - which was counted as twenty-four hours - when carrying out their functions, plus cab fares on top. But complaints were made regularly about excessively large deputations going about on business little to do with the reservoir.

Questions were asked why so many councillors and their families needed to hold a “picnic” at the facility destined to receive Thirlmere supplies, Woodhead Waterworks only 17 miles from Manchester.

In 1884, Joseph Scott, the council’s elected auditor angrily dubbed these events “pleasure trips”. He suggested that the generous expenses offered by the council were encouraging people to abuse the system.

He said: “ 21/6 per day plus first-class railway fare. is an offer which is difficult to refuse,” and asked: “What reason is there why five or ten members should go on a deputation, when one or two would represent the wealth, wit, wisdom, and every other necessary qualification of the Council?”

Scott complained that the “annual trip” of the Manchester Waterworks department to Woodhead that year had required the council to pay single rail fares for 69 people, a banquet at 25/- per person for 70 people, and travel back to Manchester by bus.

He said this was clearly a gross extravagance and an unjustifiable expenditure on the rates, but it had become an annual tradition. One “pic-nic” to Thirlmere, which lasted for 9 days, involved five councillors and one official. It happened when the Council were negotiating land purchases in the Lake District and involved entertaining of local Cumbrian landowners. This might just about have been justified.

But Scott queried how the party defended submitting expenses for spending on wines and spirits totalling £90,178 (£6,000 in 2023) which seemed a very large amount of alcohol to drink in such a short time.

He suggested it was unnecessary for so many aldermen to travel first class, and “the cost could be reduced nine-tenths.” Scott’s frustration seems justified because the council had no policy for ensuring the expenses paid out were actually related to council business at all, but members voted to take no action on his complaints.

The behaviour of Alderman Grave was more serious. The son of a Cockermouth saddler, he had moved to the boom town of Manchester to find a highly successful calico printing business and had become mayor three times. Elected to the council in 1856, he became very highly regarded in council circles. He manoeuvred to become chairman of the Waterworks Committee in 1869 — converting Thirlmere into a reservoir had been his brainchild.

He lobbied the other members to get construction underway rapidly to head off a water shortage crippling the city’s cotton mills and beat cholera. But he became ensnared in a scandal surrounding the arrest of the council’s chief clerk and bookkeeper in the Waterworks Department, Frederick Heaton, who had embezzled a large amount of money.

The trial found that Grave had used the money intended to buy land beside Thirlmere as a source of free loans for his firm.

Grave claimed he had no personal bank account and had made few transactions using the Waterworks money. Both statements were found to be untrue, so he was forced to resign.

Amazingly, the committee had nothing but praise for the crooked Grave, issuing a statement on his departure: “That this committee, while regretting the circumstances which have led to the resignation of Alderman Grave, desire to place on record their appreciation for his long and efficient service as Chairman of this committee.”

Grave seemed to have delusions of grandeur. He continued to call himself Lord of the Manor of Legburthwaite and Wythburn. This was a title attached to a parcel of land the council had bought, not a personal honour. But Manchester’s powerful committee chairmanships were normally for life and he therefore considered his position as personal rather than one of public trust.

At that time, such senior officials saw themselves more as proprietors of a business with the right to conduct them as they saw fit, rather than elected public servants.

This led the Victorian social reformer Beatrice Webb to complain that the typical local authority committee chairman saw himself as accountable to no-one: “he resents mightily any criticism of his policy or methods.”

Grave died in 1891, three years before the water supply was switched on. After the scandal toppled him, Grave retired to Portinscale where he built a grand residence, the Towers. Grave augmented his property with an ostentatious gothic coach house, sporting steeples and cloisters. Locals warned him that the ground between the lake and road was too wet to support such a thing. When he refused to listen, they termed the building, “Grave’s folly” and it duly sank.

This is an extract based on a chapter from a new book, The Trophy at the End of the World. You can buy it instantly here:

Buy

Or you can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick or Carlisle and Sam Read in Grasmere.