The surprisingly good life of the first Cumbrians

Astonishing evidence from Ravenglass that innovative pioneers lived an abundant Stone Age existence 8,000 years ago

For a long time, historians and archaeologists thought it was impossible to say much about the first people who lived in Cumbria.

The stone age pioneers who ventured into the mountainous north west of England thirteen thousand years ago just as the glaciers of the last ice age were melting were a simple and primitive people, they said.

These early hunter-gatherers led a harsh, precarious, rootless lifestyle and their nomadic existence did not leave much trace, it was argued. They concentrated rather timidly on foraging along the seashore, beside lakes and along rivers, rarely venturing into the heavily forested interior.

They failed to innovate, remained ignorant of farming, didn’t plan and seemed incapable of manipulating their environment. According to the received wisdom, hunter-gatherers were peaceful.

They lived in small bands in a state of equality without chiefs or kings and the concept of private property did not exist for them.

They lived by opportunistically hunting wild animals and birds, gathering leaves, roots and fruit from plants, catching fish and shellfish. Even their homes were not permanent - they carried the skins they used to build their tent-like houses from site to site.

It almost seemed the academics looked down on these middle stone age, or Mesolithic, people. They were portrayed as the uninteresting filling in the sandwich between the heroic big-game hunters of the Palaeolithic Old Stone Age and the triumphant Neolithic farmers of the New who, allegedly, invaded Cumbria and, ahem, “replaced” them.

Now evidence is emerging that turns all these assumptions upside down.

Excavations, particularly on the Cumbrian coastal plain at places such as Morecambe Bay, Eskmeals near Ravenglass and the Solway shore suggest that the traditional downbeat view of Mesolithic people is wrong.

Far from being lethargic stick-in-the muds, the idea that they lacked the energy to invent anything new for five thousand years is not only misplaced, but the evidence of a highly inventive community of early Cumbrians being unearthed means the story of British prehistory needs to be radically rewritten.

All this matters if we are to understand precisely who Cumbrians really are.

The point is the people who moved into Cumbria after the last big freeze are not some remote irrelevance - they are our direct ancestors. As an Oxford University team under Bryan Sykes, Professor of Human Genetics, discovered through DNA analysis, most of the people who live in Cumbria today can trace their lineage back to one or other of those Mesolithic immigrants.

Sykes found that the the first Cumbrians travelled all the way from the coastal regions of Spain more than 13,000 years ago, following the retreating ice. Now, some important excavations along the shore just below Ravenglass are starting to tell the story of how they lived.

We need to be clear what we mean when we refer to the first people to inhabit Cumbria. The truth is that human-like creatures had been living in Britain off and on for at least a million years.

Evidence for this was discovered at Pakefield in Suffolk, where archaeologists found stone tools that were between 950,000 and 700,000 years old.

But those people weren’t us. They belonged to Homo Antecessor, an extinct human species whose most obvious characteristic was a distinctly flat face. Homo Antecessor existed before the human species split into Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens. When Homo Antecessor lived here, Britain enjoyed a Mediterranean climate and food supplies were abundant. There have been five major ice ages in world history.

The last one took place between 115,000 – 11,700 years ago when glaciers up to 2,000 feet thick scraped and gouged the Lake District mountains.

If any humans did visit Cumbria before then, the ice has destroyed all the evidence. The signs are that homo sapiens waited out the ice age in a warm Iberian refuge, and then followed the herds north, most likely by boat, as the glaciers retreated, probably reoccupying places their ancestors knew.

At first, the Cumbrian hills were covered in a relatively sparse scrub known as park tundra made up of birch, juniper, willow and hazel trees. Temperatures could still get down to minus 20 or 30 degrees centigrade.

As things warmed up, the tundra was replaced by a more open landscape of grassland punctuated with small copses of trees and the occasional swamp filled with sphagnum moss. Over time, the big game animals that stone age people hunted such as mammoths, which were not well suited to the warmer weather, went extinct - forcing humans to adopt new tactics to feed themselves.

In the past, many commentators have been disparaging about Mesolithic people. Jacquetta and Christopher Hawkes, who were prominent archaeologists in the 1930s, sniffed: “Any modern visitor to Mesolithic Britain would hardly be able to guess that anything…momentous was astir.”

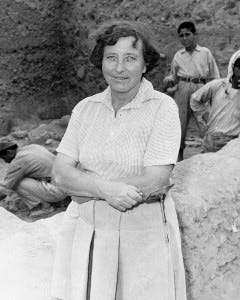

Archaeologist Dame Kathleen Kenyon who was active in the 1950s wrote that they were “in some ways rather a poor, struggling stage in man’s development”.

The popular Very Short Introduction to Prehistory published in 2003 by Oxford University contains entries for the Old Stone Age (Palaeolithic) and the New Stone Age (Neolithic), but nothing for the Middle Stone Age (Mesolithic).

In the early 2000s, historian Rodney Castleden declared hunter-gatherers barely “scratched a living”. But the latest evidence contradicts these gloomy assessments.

The first people to live in Cumbria inhabited caves in the limestone cliffs above the plentiful fishing grounds of Morecambe Bay. Archaeologists unearthed small flint blades and elk antlers dating back to 11,000 BC in Kirkhead Cave near Grange-over-Sands. Less than a mile away, a large angle-backed flint blade turned up sealed beneath a stalagmite in Lindale Low Cave at the mouth of the River Kent.

Eighty more tiny flint blades and reindeer bones were found across the estuary in another cave called Bart’s Shelter, near Aldingham.

This tells us that a community of hunter-gatherers had, under pressure from the disappearance of larger game, adopted new technology in order to survive. Instead of the relatively crude, heavy, hand-held flint axes and spear heads that the Old Stone Age people relied on to bring down bigger slower-moving prey, these Mesolithic people took up sophisticated new weapons to capture more fleet-footed creatures, while at the same time making the most of scarce resources.

For example, the Morecambe Bay finds show that they had learned to chip off smaller but sharper blades from their scarce supply of flints which are almost entirely absent from Cumbria. These longer, wafer thin shards are known as microliths.

The Mesolithic people were skilled at gluing these triangular, square, or trapezoidal flakes onto arrow shafts, harpoons and spears. When cemented with resin into a groove in a piece of wood the microliths kept a cutting edge longer and were deadlier than a single piece of brittle flint.

The evidence, then, suggests they were highly intelligent people who were hardly struggling to make their way. It is also not true to say that the middle stone age people had a scant or un-nourishing diet.

Now archaeologists have discovered that early Cumbrian people moved north from Morecambe Bay and settled at several sites in and around the Eskmeals foreland south of Ravenglass.

These pioneers set up not temporary, but permanent, villages on the seaward-facing slopes of the escarpment that rises above the River Esk. Eskmeals is now regarded as the best example of a Mesolithic site in the whole of Britain.

The coast was a combination of salt marsh, sand dune, rocky cliff and headlands. The drier ground was capped by wind-strafed scrubland grading into taller forest inland. The incomers chose the area well because it combines a river, an estuary and a seashore in one place and thus it offered a far greater variety and abundance of food along with sand and stone for building shelters than a purely coastal location.

Despite previous gloomy assessments, it turns out Cumbria’s wild food supply was bounteous for much of the Mesolithic period. The renowned geographer Jared Diamond wrote that they had a better balance of protein and nutrients than the Neolithic farmers that followed them. Farming drastically limited the range of food available to a family, and it was excessively focused on carbohydrates, Diamond said, although Neolithic societies were able to produce more food than hunter-foragers and support denser populations.

However, the relative abundance that the first Cumbrians enjoyed faced a severe challenge. Immediately after the glaciers retreated, Britain was still connected to the Continent by a land bridge about the size of Wales that we now call Doggerland.

A flat, fertile plain laced with rivers and wetlands, Doggerland was one of the richest areas in ancient Europe for hunting, fishing and bird catching. But then in 6,500 BC a catastrophic tsunami submerged the low-lying land permanently under the sea and broke Britain’s connection to Europe.

Thousands of early people drowned in the cataclysm and the survivors were forced to move to higher ground either on the Continental mainland or on the newly created island of Britain. Although the absolute numbers of Mesolithic people were never large, any influx would have put great pressure on the existing population.

This is because a hunter-gatherer band the size of an extended family required access to between 500 and 700 square miles of land to find the food they needed to survive. Based on this maths, the whole of Britain could have supported a total of no more than 10,000 hunter-gatherers, a few hundred of them in Cumbria. This was the stimulus for a another momentous revolution: the violent introduction of farming into Cumbria…

This is an extract from my book Secrets of the Lost Kingdom. You can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth or Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle. It is also available at the Moon & Sixpence coffee bar at Lakeside in Keswick and Sam Read’s in Grasmere.

You can also buy online at Fletcher Christian Books.