The sugar baron and the sprinting slavegirls

Maryport landowner William Senhouse sired 100 children at Barbadian plantation he called “Little Cumberland in the West Indies”

One night in the late 1770’s an extraordinary vision appeared briefly in the ancient Cumberland village of Brigham.

It is said two elegantly dressed but clearly terrified young women, barely out of their teens, were glimpsed running through the tall gravestones surrounding St Bridget’s church.

This might have gone unnoticed but the women seemed to be wearing low-necked gowns open in front to show their petticoats, as was fashionable then.

And, in the few moments before the pair were captured rather roughly by a man in gamekeeper’s clothes and his two nimble assistants, an onlooker might have been able to discern through the gloom the amazing fact that the lovely women with vermilion painted lips were black.

The fugitives were never spotted in public again and nothing further was heard of this incident, their wellbeing or their eventual fate. Few newspapers circulated locally at this time and the weekly that did exist, The Cumberland Pacquet, that began publication in Whitehaven in 1774, never carried a line about them.

How, then, did the unhappy women end up running in a frenzy through a Cumberland churchyard? It seems highly unlikely that they were Cumberland residents. They could conceivably have arrived by sea.

By the late 18th century Whitehaven was the sixth largest port in England with a fleet of 448 ships regularly sailing to and from Virginia, Maryland and Pennsylvania in America. But how do we explain the rather discourteous welcoming party they ran into among the gravestones?

There is little doubt that the gamekeeper and his helpers worked for one of the pre-eminent gentry families of Cumberland. Amongst the most likely candidates are the Senhouses, who lived seven miles away at Netherhall, a large red sandstone mansion outside the booming harbour town of Maryport, a place buzzing with factories, coal trading, iron smelting and ship building.

In fact it was no coincidence that William Senhouse, a former Surveyor General of His Majesty’s Customs, had recently returned to his Cumbrian estate to take a respite from his labours as a well-heeled gentleman planter on the sugar island of Barbados. A rest from the 31 degree heat and 81% summer humidity was necessary every few years.

To really get to the bottom of this story, we need to know more about the Senhouse family and their milieu. They were a wealthy old Cumberland landowning dynasty that had lived at Netherhall since the 16th Century.

At that time the town was called Ellenfoot, named after the confluence of the river Ellen with the Solway. Its owner, Humphrey Senhouse, was a Tory politician and the influential High Sheriff (the Sovereign’s local representative) of Cumberland. He had married an heiress called Mary who was the daughter of Sir George Fleming, Bishop of Carlisle. William, the couple’s third son, was born at Netherhall on 16 January 1741.

Humphrey, who later achieved fame as the excavator of the town’s Roman past, had much money invested in the West Indies. In 1756 he changed the town’s name to Maryport after he and his wife began developing the harbour. He wanted to emulate the phenomenal success of Whitehaven fourteen miles to the south that the Lowther family had turned into the second busiest harbour after London and a major port for trading slaves to the American colonies.

It came time to decide William’s future. In the Georgian period, second or third sons who were not especially clever and who were not in line to inherit the family estate traditionally went into the armed services or the church. William duly went to school locally and then attended Cockermouth Grammar School in preparation for entering the Royal Navy as an officer. However, his hopes of rapid advancement up the navy’s ranks were scuppered by his obvious mediocrity.

He languished as a mere midshipman from 1755 to 1769, and did not distinguish himself in the Indian Wars when the British defeated a French force that had been besieging Madras. He failed to stand out even during his posting to the North American port of Boston that was seething in the run up to the American War of Independence.

Realising he was not rated by his superiors, he quit to become an official in the notoriously corrupt British Government customs service overseeing the taxation of sugar. He lived in Barbados except for when he made short visits to other islands and several longer trips back to England.

Within three years he married Mary Samson Wood, daughter and heiress of a well-to-do Barbados planter. Together they had eight sons and three daughters - there was clearly not much to do on the island.

It was then that William’s Tory party family connections started to pay off. England’s wealthiest commoner, Carlisle Tory MP Sir James Lowther, whose father Robert had been Governor of Barbados, pulled strings to get William a huge promotion.

He became Surveyor General of the Customs in Barbados, the Windward and Leeward Islands. His job was to collect the four-and-a half per cent duty levied on exports of colonial produce such as sugar, tobacco and rum for the British Treasury.

It was a plum post because the Conservative Government in London was swinging the burden of taxation away from land (which pleased its supporters massively) and onto things that the mass of the people consumed, such as the sugar in their tea. This is still the party’s policy today.

William’s leg-up was part of a lucrative back scratching arrangement between the Senhouses and the Lowthers. Sir James was prepared to help out as long as he received big favours in return. It is difficult to overstate the power of Lowther, a Whitehaven landlord and coal owner.

You can buy this book by clicking here

Known variously as “Wicked Jimmy”, “ Jemmy Grasp-all” and the “Earl of Toadstool” because of the time he conjured up bogus voters out of thin air overnight in a Carlisle election, he controlled nine MPs in Parliament. Through a system of barely-concealed bribery, intimidation and election rigging Lowther effectively owned the town of Cockermouth and he was the power broker who set William Pitt The Younger on course to be Prime Minister by ensuring he became Tory MP for Appleby.

William served for twenty-three lucrative years as a civil servant. Then he suddenly produced the £18,000 (2020: £2 million) he needed to buy his own sugar plantation, The Grove in St Philip’s on Barbados, complete with 113 slaves. “From a run-down condition, he improved the plantation until it became a productive property with a comfortable house for his growing family” William’s son, Humphrey Fleming Senhouse, recorded.

William paid his sponsor back by running a similar estate called the Christchurch Plantation with 128 slaves on Lowther’s behalf. Slave plantations were extremely expensive and complicated to manage (we will see what that means later). But in the long run they could be extremely profitable.

By 1800, slavery and its associated businesses accounted for no less than sixty per cent of all Britain’s trade. The profits from slavery made an important contribution to financing Britain’s Industrial Revolution. Lowther’s traditional English estates brought in more than his slave estates, the 2020 equivalent of £6 million a year. But his English money was spoken for, so the profits from his Barbados sugar plantations were crucial in helping him expand his land holdings.

William's brother, Joseph, emigrated to the West Indies at the same time as William. He became a considerable slave-owner, too, with a coffee plantation in Dominica. He called his plantation “Lowther Hall” in honour of his family's benefactor and William called his Barbadian plantations “little Cumberland in the West Indies” because so many Cumbrians found employment there through the Senhouses and the Lowthers. Men such as these had the power of life and death over their slaves and so had few scruples about how they treated their bodies.

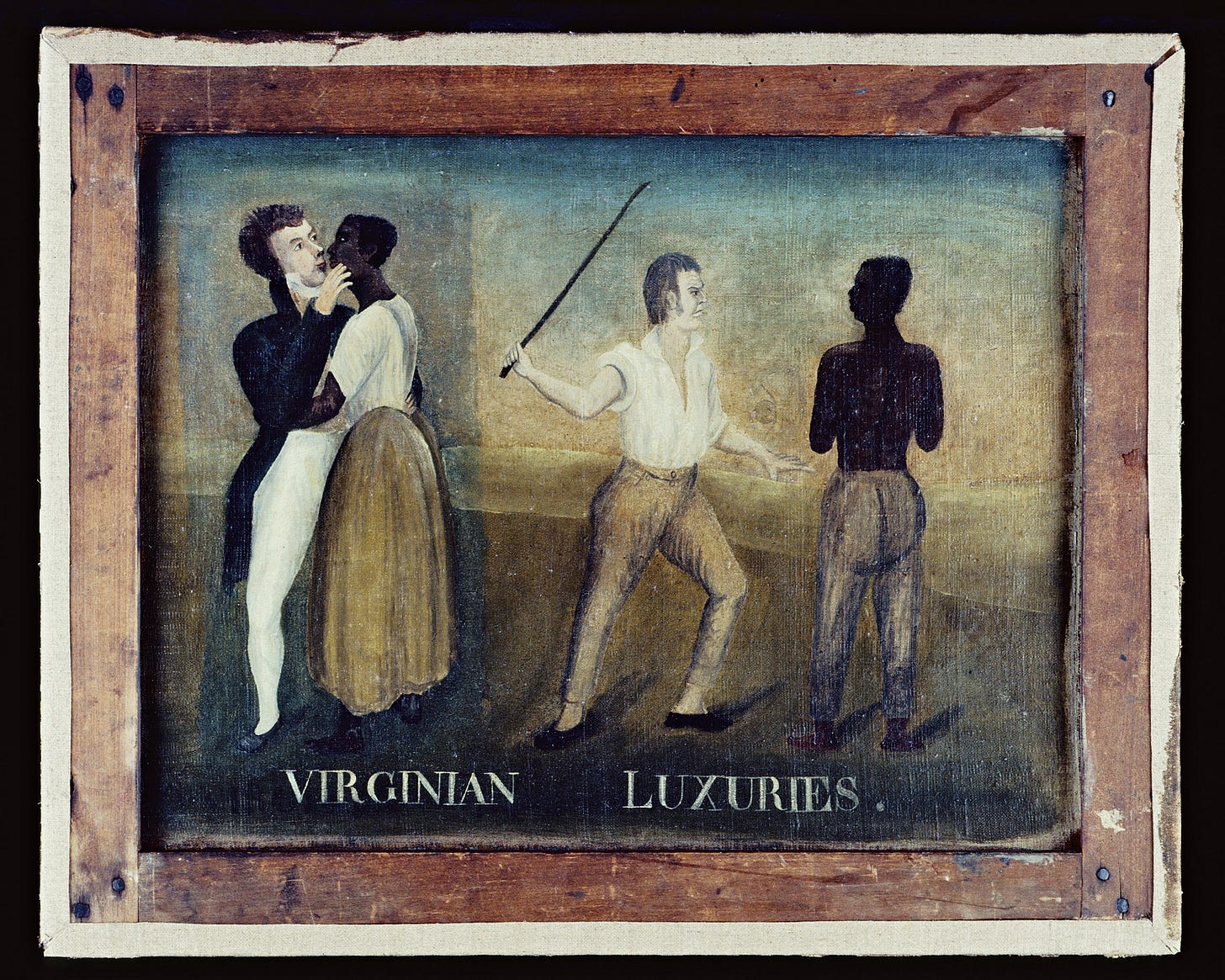

One report said William Senhouse chose his slaves “not for their agility, strength or intelligence, but for their beauty. He did not discriminate between male and female for his sexual pleasure: William Senhouse took a delight in them all.” His sexual appetite was legendary and it is estimated that he sired 100 children. The completely untrammeled freedom with which Senhouse was able to indulge himself in black flesh on the island eventually blinded him to what was acceptable when he not infrequently visited Britain…

…..

This is an extract from a chapter from our gripping new book entitled “People of The Sacred Valley” which tells the histories of remarkable individuals who lived along the banks of the Derwent River in Cumbria.

You can pick up a copy from The Moon and Sixpence Coffee House or the New Bookshop, both on Main Street, Cockermouth. It is also available at Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Or you can buy it instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/details/p5921133_21146598.aspx

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.