The real person behind Merlin legend

He was the fabled wizard, teacher and guardian of legendary King Arthur. New research says he was based on noble warrior driven out of his wits by a horrendous Dark Age battle in Cumbria.

Merlin, the great wizard and central character in the legend of King Arthur, was based on a real man in Dark Age Cumbria, according to the latest research.

Thousand-year-old manuscripts show that the story of the magical guardian of Britain’s most famous ruler was inspired by an actual individual.

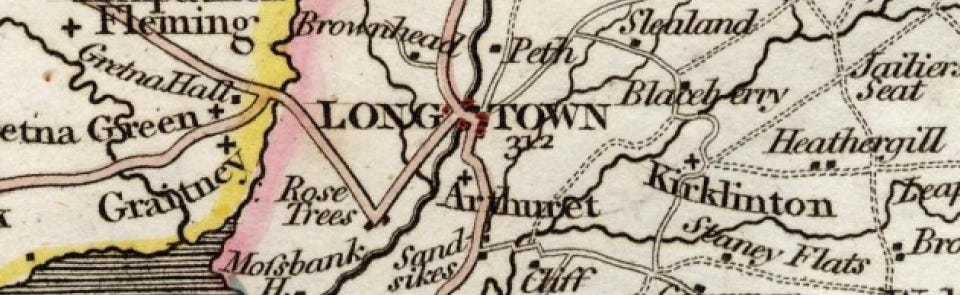

The elusive figure is believed to have been a noble warrior who fought for Cumbrians against the Scots at the Battle of Arfderydd, or Arthuret, near Longtown, Cumberland, nine miles north of Carlisle in 573 AD.

The violent clash was a real historical event. It is recorded in a 10th Century chronicle known as the Annales Cambriae (the Annals of Wales). The battle turned into a grotesque bloodbath that lasted six weeks.

Three hundred men were killed and buried nearby. Despite appearances, the name Arthuret has nothing to do with King Arthur. It comes from the Welsh word Arfderydd which can be translated as “burning weapon” or “scorched by arms”.

So appalling was the slaughter in this military encounter that the Merlin-figure was overcome by grief and horror.

Driven to distraction by sorrow and terror, the battle-hardened fighter broke down with what we might today recognise as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and wept for the young Cumbrian warriors cut down in their prime.

The bloodletting ended when the Britons finally drove the Scots from the field. But Merlin fled the battle to seek solitude in the forest where his obsessive and hysterical talk was taken to indicate that he had developed uncanny powers of prophecy.

Geoffrey found accounts of Merlin’s descent from proud warrior to gibbering wild man in six poems preserved in a 13th Century compilation known as the Black Book of Carmarthen. These verses feature a first-person narrator called Myrddin who makes various predictions about the future. Geoffrey decided to change the character’s name to Merlin, some say, because Myrddin was too close to the French word merde, excrement.

On these Cumbrian foundations, as the brilliant historian Tim Clarkson has suggested, Geoffrey and a string of poets over the centuries built the mythical literary character of Merlin into the figure that we know today, a powerful magician, shape-shifter and seer. Tim wrote that historians had identified the Merlin-archetype, the individual on whom the later stories were based: “The evidence suggests that he actually existed, that he was a real person,” he wrote.

Many people are puzzled about why accounts of people and events from northern antiquity are found in Medieval Welsh books. The answer is that the people of Wales and Cumbria were descended from the same people, the Ancient Britons, who were the original inhabitants of the island. Britain, after all, means “Land of The Britons”. They enjoyed a shared culture, literature and spoke closely-related Celtic languages. Until an Anglo-Saxons incursion into Rheged divided them geographically from each other in 730 AD, they were connected.

The Welsh kings told their court bards to write about heroic northern British kings of the fifth and sixth century - the period historians call the “Heroic Age of the Cumbrian Celts” - to inspire their own soldiers to fight against the encroaching Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

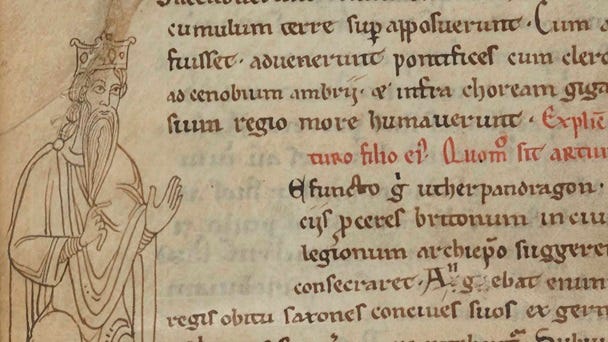

The popular conception of Merlin comes from a twelfth century work written by a Welsh cleric called Geoffrey of Monmouth. It was called the History of the Kings of Britain, published around 1136, and it became a medieval bestseller.

But Geoffrey also wrote a second, less well-known, book about Merlin which came a dozen years later that explored Merlin’s origins. It was called ‘Vita Merlini’ (‘Life of Merlin’). The two books present the wizard as rather different characters.

We need to bear in mind that in both these books Geoffrey was not offering the literal truth. Medieval readers would have been quite comfortable with the idea that Geoffrey was writing a sort of pseudo-history in which fact and legend are skilfully interwoven.

Geoffrey’s first book, the History, became hugely popular because it offered a new, exciting and colourful version of two thousand years of political intrigue. It was eagerly received by his readers all across Europe and therefore Geoffrey’s impact on the literature that was written in the wake of his amazing volume cannot be underestimated.

In this first book, Merlin enters Geoffrey’s myth-infused story at the point when the British King Vortigern has become angry. The foundations of the new fortress he was trying to build kept disappearing each night. The king’s advisers told him the only way to thwart the mystical forces gobbling the stonework was to sprinkle the blood of a fatherless child on the site, a human sacrifice believed to be a part of ancient Celtic ritual.

The king’s soldiers found a suitable young sacrifice in Carmarthen in Wales and dragged the boy before Vortigern. But Merlin stepped in to save the child by declaring the real problem was a fight between a red and a white dragon in a subterranean pool under the fortress’s cellars.

The red one, he explained, were the Britons, and the white their Saxon foes. Merlin then prophesied the Saxons would eventually conquer most of Britain (which of course happened).

Elsewhere in the narrative, Geoffrey credited Merlin with magically moving Stonehenge from Ireland to Britain and gave him a role in Arthurian legend. Merlin, Geoffrey wrote, disguised Arthur’s father Uther Pendragon so he could sleep with Igerna, a Cornish noblewoman, another man’s wife. It was through this deceit that Arthur was conceived. It was in this book that Tintagel, a romantic cliff-top castle in Cornwall, gained literary fame when Geoffrey named it for the first time as the place where conception took place.

However, Merlin does not appear in the largest section of the book - the part that concerns Arthur’s later career. In fact, Geoffrey’s Merlin remains his leafy exile throughout the rest of Arthur’s legendary life. But Europe was transfixed by Geoffrey’s account of Merlin’s exploit’s - and the fabled wizard’s prophecies were widely discussed across Europe.

Geoffrey had created a phenomenon that other writers could not resist. In the mid 1150s the Norman poet Wace adapted the Latin translation of Geoffrey’s history to create the Roman de Brut (‘Romance of Brutus). This was a Christianised history full of tales of chivalry and country love that added significant new elements to the Arthur myth, such as the Round Table.

In around the year 1200, the Burgundian poet Robert de Boron deepened the Christian content of the Arthur story. He used Wace’s version of Merlin as the basis for his own narrative poem ‘Merlin’. This formed the second part of a trilogy on the legend of the Holy Grail. The Grail is traditionally thought to be the cup that Jesus Christ drank from at the Last Supper and that Joseph of Arimathea used to collect Jesus's blood at his crucifixion.

Boron also gave Merlin a more central role in Arthur’s story. It is in his version that the wizard becomes the future king’s mentor and he appears as more of a trickster and shapeshifter. Crucially in this version, Arthur’s father Uther orders the Round Table to be made and Boron introduced the magical sword firmly embedded in an anvil on a block of stone, fixed there by Merlin’s sorcery.

The wizard caught the imagination of several anonymous authors. French versions of the Merlin tale became hugely popular across Europe.

Merlin plays a significant, though slightly diminished, role in Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. His 1470 version was written during a stint in Newgate Prison after Malory was convicted of plotting Edward IV’s overthrow. Malory introduced Arthur as a chivalric king, his unfaithful wife Guinevere, Sir Lancelot of the Lake, Sir Gawain and the other knights of the Round Table with Merlin relegated to his modern guise, wise counsellor and minster, rather than his earlier persona as mighty seer and powerful sorcerer.

But, as noted earlier, this was not the only Merlin book that came from Geoffrey’s pen. His ‘Vita Merlini’ (‘Life of Merlin’) never attracted the acclaim of the earlier one but it is vital for understanding where the character came from.

Geoffrey’s second work about the wizard was produced probably in around 1150. It presented a different Merlin, reinvesting him with his full powers as a prophet and sorcerer and moved the geographical setting from Wales to the Kingdom of Cumbria.

The Vita appeared probably in around 1150. It presented a different Merlin, reinvesting him with his full powers as a prophet and sorcerer and with the geographical setting moved from Wales to the Kingdom of Cumbria. Geoffrey did not do this on a whim. The change came about because he was working from a different source , one with its origins in the north.

Geoffrey had portrayed the first Merlin as a servant of the King of Dyfed in South Wales where he was chief seer and law-giver. But the second Merlin is shown to be living in the north and supporting the British leadership in a landmark war with the Scots. Merlin, wearing a gold torc of authority, accompanied the legendary leader of the Britons and ruler of the “north Welsh”, King Peredur.

This king was a member of the Coeling dynasty that had ruled northern England since the departure of the Romans. Peredur was a cousin of Urien, the powerful sixth century king of Rheged, the land we now know as Cumbria and a hero to the Cumbrians. Against him was Guennolous, the ruler of Scotland.

Peredur’s brothers were slain at Longtown during a brave charge through the Scottish line. Witnessing so much carnage proved too much for Merlin.

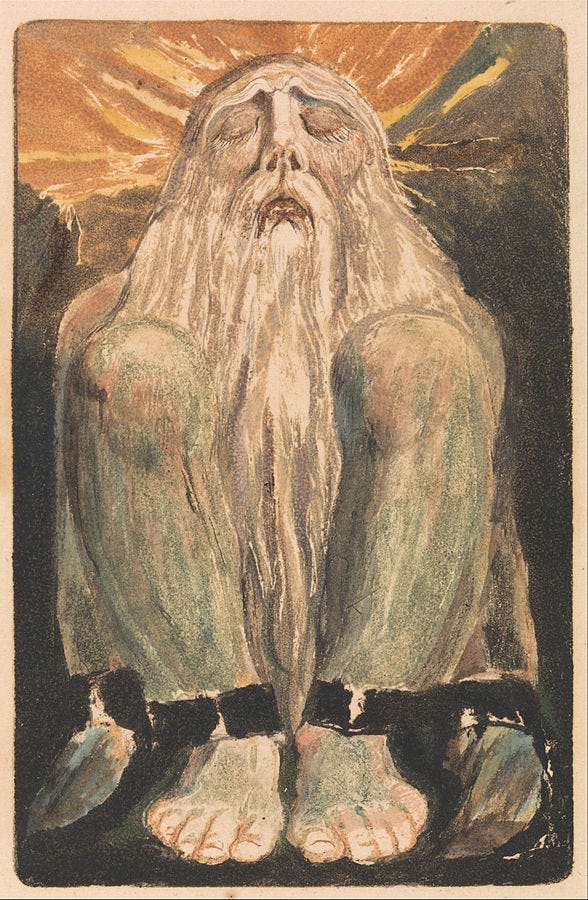

Merlin was unconsolable. “He threw dust upon his hair, tore his clothes and lay prostrate on the ground, rolling to and fro,”

“He threw dust upon his hair, tore his clothes and lay prostrate on the ground, rolling to and fro,” Geoffrey wrote. The wizard would take no comfort from anyone, not even Peredur and his victorious commanders. Merlin manifested a “strange madness”.

For a whole summer he sought solitude among the Cumbrian trees, living as a wild creature, foraging for roots and berries “lurking like a wild thing,” Geoffrey added. As winter came and Merlin could no longer pick food from the branches the Britons sent out a search party and found him on top of a mountain. Told that his wife, Guendolena, was pining for him, Merlin agreed to leave the forest.

He was greeted by great crowds of cheering nobles whose noise pitched him straight back into madness. Rodarch, King of the Cumbrians, ordered that he be imprisoned for his own safety. Eventually, Merlin was allowed to return to the forest where he made a whole lot more prophesies (which the readers know are all accurate because the events had already happened).

According to Geoffrey, King Arthur’s entire career unfolds while Merlin’s is lurking in the wood. Uther’s illegitimate son succeeds to the throne by pulling the sword Merlin fixed there from the stone. He is betrayed by his wife, is mortally wounded and is borne to the Fortunate Island.

Merlin, still in the woods, is in conversation with Urien’s court poet Taliesin when news came that a spring had appeared at the base of a nearby mountain. When Merlin drank from it, his madness miraculously disappeared.

So, why is the second version of Merlin portrayed as living in Cumbria? The answer is: because Geoffrey’s new material came from northern sources. The research shows that the story of the wild man in the forest originated after a real Cumbrian noble, whose mind was turned by the horrors of the battle near Arthuret in 573 AD, fled to the forest.

This piece is from a forthcoming book. You can read the rest by signing up. Or you can get more like it by buying one of my other books here:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.