The Langdale Axe

Why Neolithic Cumbrians braved bears, wolves, lynx and a 2,000 foot drop to create a Stone Age wonder tool

By Paul Eastham

At the centre of the Lake District there is a mountain peak shaped like a scoop of ice cream.

The sides of this eminence are sheer and the view from the top is sensational.

Standing over 2,000 feet, the dome of Pike o’Stickle is visible 100 miles away on a clear day.

It is a magnet for advanced fell walkers, but most do not realise that clinging to its slippery flanks is one of the world’s first factories.

If you step aside from the main path and peer down towards the weir on Mickleden Beck far below you will see an enormous scree slope.

It is a six thousand year old waste tip filled with shattered rock thrown aside by Neolithic artisans. This was the by-product of a Stone Age industry.

Beginning in about 3,700 BC miners used fire to crack open the cliff and out of the hard, fine-grained volcanic greenstone that fell down, they manufactured large, polished axes.

These deep blue-green tools were highly prized by late Stone Age people across Britain and Ireland. Yet there is something odd about the entire enterprise. The makers could have extracted similar greenstone from more reachable sites than this one in Great Langdale.

Flint was an alternative material for making axes and it was available from at least 30 other sites around Britain including the chalklands of southern England.

So why choose greenstone hacked out of this most inaccessible and difficult terrain high up in mountains? The Central Lake District fells are frequently snow-bound, shrouded in mist and surrounded by dangerous precipices. The Pike’s rock was not notably more effective at chopping down trees than razor-sharp flint blades.

It is an even more puzzling problem because although today the valley is virtually treeless with grassy slopes gnawed smooth by innumerable sheep, six thousand years ago the Neolithic prospectors would have had to fight their way there. The route to Pike o’Stickle lay through a threateningly dark and knotted oak, rowan and birch forest infested with wolves, bears, lynx and aurochs to reach the cliff.

In fact experts believe the Langdale Axe Factory was established there precisely because it was so hard to reach. It was because the site of the quarry was in such an iconic situation that they went for it. No other source of stone was so obviously a gift from the gods.

It seems the makers wanted the source to be as far from ordinary life as possible. And the unique selling point worked. When Professor Bill Cummins examined nearly 1,840 Neolithic axes found all over England and Wales, he discovered that 27% were made from polished greenstone volcanic tuff from Great Langdale in Cumbria.

So the value of greenstone axes seems to supersede the purely functional. They appear to have played a part in displaying the status and authority of individuals and the mythology, beliefs and memories of Britain’s early agricultural communities.

It could be argued that they played a similar role in the Stone Age economy as the iPhone does in ours: they were an extremely powerful new technology, sure, but they also acted as a potent status symbol and gave a huge boost to the prehistoric economy.

Whether you buy the analogy or not, the Langdale axe was the defining artefact of the period. Like our expensive mobiles, these beautiful, polished choppers were not only the crucial tools that enabled the first farmers to clear the forests to grow the food on which their precarious lives depended, they were also objects of great symbolic power. They signified social rank and influence, combined with a cultural and ideological statement.

The archaeological record shows that prehistoric people loved exotic materials. They quarried unusual coloured volcanic stone all over the west and north of the British Isles and these objects travelled a long way, transforming society as they went.

JPMorgan Chase’s chief economist Michael Feroli said the US economy grew at 2.3 per cent in 2017, and the iPhone alone was responsible for the 0.3 per cent of that. In a $20 trillion-a-year economy, that’s a lot.

The Langdale axe had a similar impact on Neolithic Cumbria, Britain and Ireland, as we will see. The axes were “roughed out” to the right size on top of the mountain, and then taken down for finishing. It was an arduous business because horses were not domesticated in Britain for at least another thousand years.

The workers dragged the stones along the valley floor using rollers on timber trackways built using locally available wood. They selected birch for its whiteness and visibility amongst the greys and browns of the mud. Roughed out axes ended up at polishing centres nestling at the bottom of the Lake District valleys.

One such site at Ehenside Tarn, five miles south of the St Bees beauty spot, was discovered in 1869. A local farmer drained the tarn and found a large number of stone age artefacts at the bottom. The finds included lots of pottery, flint and stone tools, polished axes and, most unusually, two wooden paddles bearing axe marks which would not normally have survived 6,000 years without being under water.

He also discovered the remains of Neolithic people’s food including bones from wild and domesticated animals and nuts.

The local vicar JW Kenworthy was called in to inspect the astonishing apparition. He told the Whitehaven Herald in 1870: “along the shore was a line of white stones, burned white by the action of fire…there was a very large quantity of charcoal, burnt wood, broken twigs, nuts and leaves and some few, but not many, bones of wild cattle and perhaps deer.

“Stone and fine implements, such as axes, knives and chisels, were plentiful, still not one trace of iron, bronze or metal of any kind has come to light. The rude and primeval people whose existence these relics indicate were only in possession of implements of flint and stone.”

Excited by this report, the London Society of Antiquaries sent its expert R.D. Derbyshire to excavate the site.

He found a fragment of a wooden bowl, three wooden clubs, one of which was decorated. There were two wooden fish spears, a plain bowl and some Peterborough Ware imported to Cumbria from the south of England. It is decorated with pits made by bone or wood implements.

There was a saucer shaped stone quern for grinding corn, stone polissoirs for polishing axes and two stone axe blade rough outs. He found a stone that Neolithic families would heat in the fire and then toss into a cooking pot and a bone from a wild ox that might have been the meal.

Most amazingly, a beautifully polished stone axe blade turned up, accompanied by the wooden haft or handle to which it was attached. This unique object, now in the British Museum, is world famous.

Movingly, six hearths were spaced at intervals around the tarn. This suggests that many family groups lived in the little village, making their living polishing and putting handles on Langdale axes.

This highly organised lakeside production unit appeared at the start of a profound revolution in Cumbrian life. Ehenside was only one of many Neolithic villages that sprang up at the end of Lake District valleys dedicated to polishing up Langdale axes for the domestic and international “market.”

But making axes was incredibly dangerous and time-consuming. Why would stone age people clinging precariously to life risk doing it?

When the glaciers of the last ice age retreated about 13,000 years ago, the Cumbrian coast became gradually populated. Small groups of nomadic Mesolithic Middle Stone Age hunter-fisher-gatherers migrated there from a warm refuge in what we now call northern Spain.

Then 6,000 years ago, knowledge of farming filtered north. In Cumbria, the transition from hunting and gathering to full-on agriculture was very gradual, with families practicing a mix of both strategies for centuries.

The Neolithic people at first regarded the forested interior, understandably, as dark and dangerous. But it had to be cleared if enough garden-sized cereal growing plots and grazing land were to be found for the production of primitive emmer wheat, barley, oats cattle, pigs, sheep and goats.

Starting in the more lightly forested river valleys, they used Langdale’s stone axes to fell trees and dig out scrub that had thickly covered the land from coast.

Langdale axes are impressive objects. Often 11 inches long, three or four inches wide and weighing nearly two pounds, they are oval in cross-section. They were smoothed to a glass-like sheen in factories such as Ehenside in a process that took many weeks. Gentle abrasion eliminated weak spots and made them hard and very resistant to shattering.

And, yes, they were in huge demand. Examples have been found across Cumbria, particularly in the best farming areas, the Solway Plain where 100 of the axes have been found, the Eden Valley, the Furness peninsula and at Morecambe Bay where 67 have turned up as well as across Britain and Ireland.

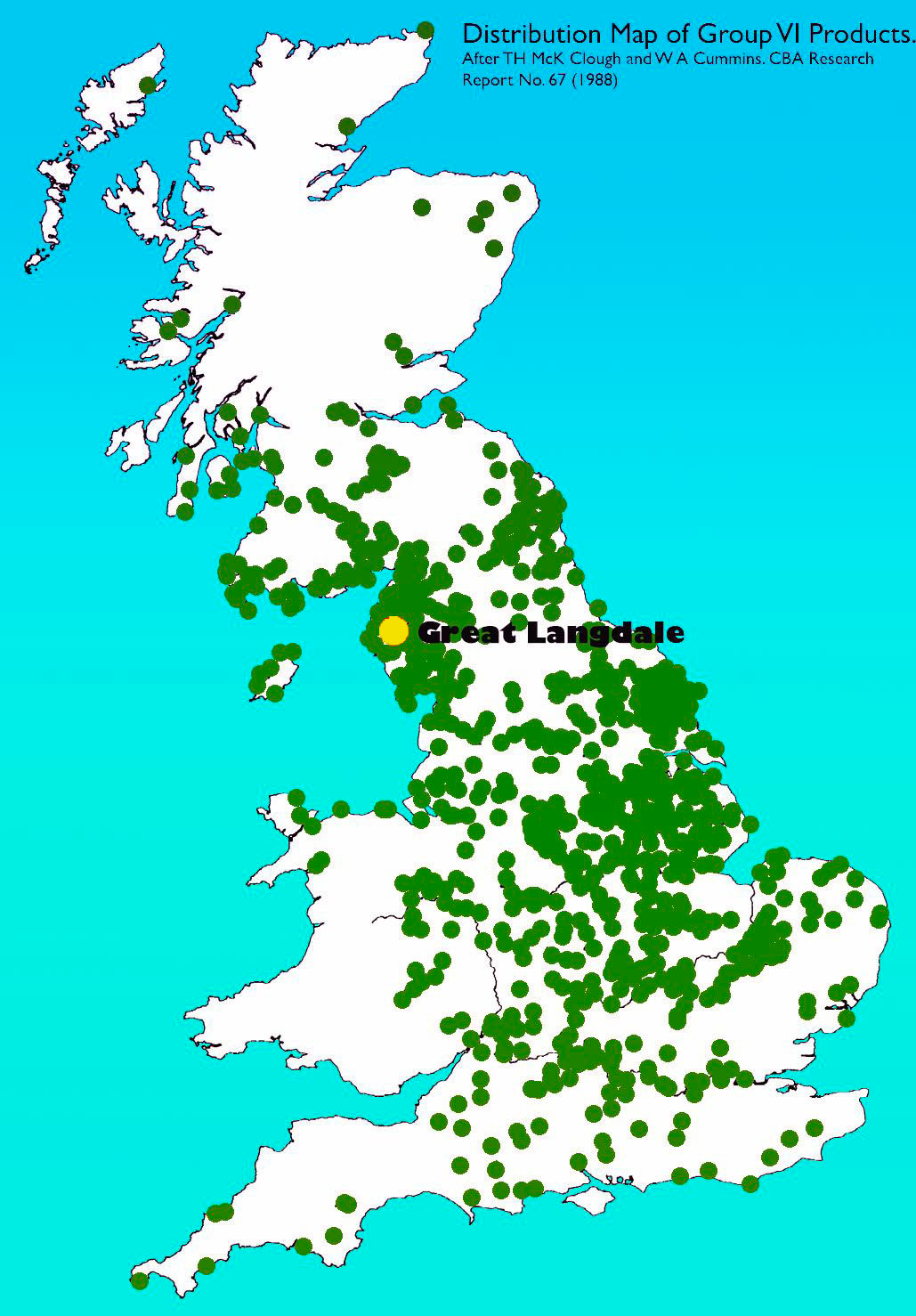

An unusual concentration of finds occurs in the East of England, particularly Lincolnshire, which archaeologist Francis Pryor believes may indicate objects from high places were particularly valued in low places. Archaeologists call Lake District axes Group VI products. The map below shows where the Langdale blades have been found.

But they did not get there by anything resembling what we call “trade.” In a world without money precious items like axes were distributed hand-to-hand to other tribal groups through a network of social contacts.

Perhaps, as in the film the Godfather, they were “gifts” in the Don Corleone sense, carrying an obligation to return a favour such as to fight mutual enemies at a future date.

A clue to the appeal of Langdale axes is that while many that have been found show signs of wear, plenty show none at all. Some were buried with the dead or placed in watery ground, a common ‘sacrificial’ practice in prehistoric Britain.

Others have been found “hidden” as votive offerings in crevices such as on Wanthwaite Crags near Threlkeld in Cumbria. But if we track the routes by which the Langdale axes travelled it is noticeable that some significant places, such as Cumbria’s fifty stone circles, lie on the “trade” routes.

Castlerigg for example near Keswick is on the route to Yorkshire where a large number of the axes has been found.

So one explanation as to why the stone circles were built is: the Langdale axes produced the wealth and the reason to build them - as ceremonial stadiums where the

ritual gift-giving took place.

The stone rings, in other words, may have been places where Cumbrian tribes demonstrated their power - and exacted tribute in return.

This article is based on a chapter from my book Huge & Mighty Forms which you can buy here.

One day In the 1950s,,when I was young and fit , I was scree running in Cumbria. Looing for the safesr way down a slope , I deciided to cross horizontally before going down hill. I ren until I reached a small flat area. Looking down I discovere I was standing on handworked stone flakes, ,a work site. To me it was magical, I wonderd hw old the site was and have never forgotten the sense of wonder.

Wonderful article and Substack collection. Thank you.