The "half dead" Vikings invade Cumbria (brandishing vanity cases)

Scandinavian trader-warriors ejected from Dublin in 902 AD colonised the north-west coast - without the traditional bloodbath.

In 902 AD, a new power loomed out of the northern seas. Monks tending vital crops in a monastery garden at a place we now call Workington spied the tall prows of several slender, 60-foot longboats.

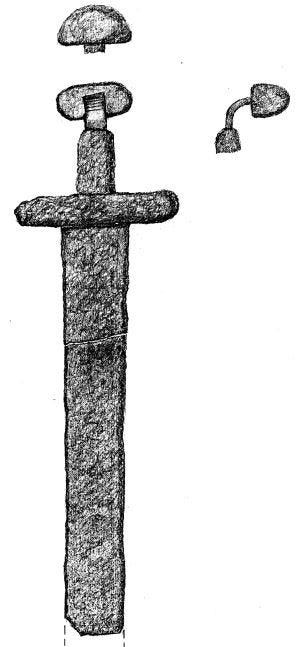

The terrified clerics knew what to expect. Each vessel would be ferrying at least 25 fully-armed helmeted warriors with shoulder-length hair, neatly trimmed moustaches and beards ready to burn buildings, steal treasures, murder churchmen, gang-rape women or take them captive to sell as slaves.

But soon after the ships slid onto the sand in the nearby natural harbour, the nervous priests realised there was something unusual about the landing parties. Many of the men on board were wounded or dying and some had to be carried from the boats on litters. A doctor, known in the Viking world as a “lach” after the word leech, moved among them lancing; cleaning wounds; anointing; bandaging; setting broken bones; and applying herbal remedies.

This time the sea rovers had not come for immediate plunder. They were here to recover from some terrible event. And they were staying for good. The Vikings would climb to the top of the mound where St Michael’s Church is today, that was the site of a very early Christian Abbey. Hundreds of years later, archaeologists would find a wealth of Viking carvings under the foundations of the church.

Where did these wounded raiders come from and what drove them to Cumbrian shores?

The few dozen buccaneers who landed in West Cumbria on that day could trace their ancestral roots to Norway. But they had lived in Ireland for a century, and had adopted a great deal of Irish culture. Warrior clans had fought for land in Norway for generations.

But there was too little to go around. So their fathers and grandfathers had raided Ireland for 40 years, striking suddenly and catching the Irish unawares. In 842 AD the war bands under the Viking king Turgeis sailed up the River Liffey to Dublind, dub meaning “black, dark”, and lind meaning “pool,” referring to a deep tidal pool where the River Poddle enters the Liffey.

They hauled their boats ashore, built a defensive “longphort,” or ship camp. Dublin became a prosperous Viking town. With a permanent foothold in Austmanna-tún (Norse for homestead of the Eastmen) the Vikings could carry on their attacks on Irish tribes and the West Coast of Britain all year round, rather than being forced to return home during winter.

Over a century Dublin became boomtown with the largest slave market in Europe. The Norsemen traded over long-distance routes to America in the west, Central Russia in the East and Constantinople on the border between Europe and Asia.

They became rich, trading amber, silk, gold, silver and multitudinous looted goods. Dublin became a noisy, crammed, hybrid of Scandinavian and Irish culture. But the ferociously competitive Norsemen feuded with each other incessantly and weakened the colony.

Then, in 902 AD, the two kings of the Irish provinces that surrounded the Viking enclave, Cerball mac Muirecáin, king of Leinster, and Máel Findia mac Flannacáin, king of Brega, exploited these internal splits. They launched a two-pronged attack on Dublin and drove the Vikings from the city after a ferocious and bloody battle.

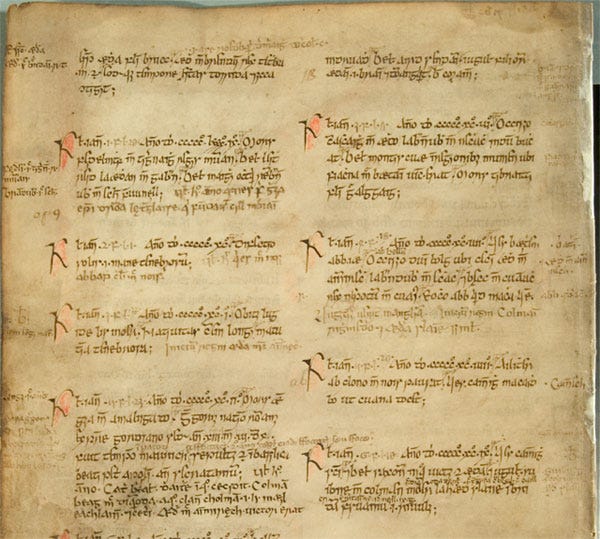

According to the “Annals of Ulster,” a medieval chronicle written by monks of Belle Isle on Lough Erne: ‘The pagans were driven from Ireland [...] and they abandoned a good number of their ships, and escaped half-dead after they had been wounded and broken.”

The expelled Scandinavians scattered, travelling to Wales, Scotland, Iceland and France, but especially north west England to try and find new land to settle on.

Historians argue fiercely about how peaceful the Norse settlement of Cumbria was. Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder, who ruled southern England and his daughter Æthelflæd who ran the Mercian Midlands, were hostile to the incursion. But the weakness of the Anglo-Saxon Kingdom of Northumbria to the east combined with the compliance of the Scots in the North appears to have made the Viking immigration relatively bloodless.

At first, the Scandinavian exiles from Dublin did not risk putting down deep roots. They merely created defensive land bases for their swift, formidable raiding fleets. The “History of St Cuthbert,” written in 1031, tells of a powerful English thegn called Alfred, son of Brihtwulf “fleeing from pirates” - after an encounter with these Viking exiles sometime between 902 and 915 AD. The incomers farmed a little too. But the Vikings took a hundred years to settle Cumbria.

This is an extract taken from my book called Secrets of the Crooked River. You can buy the book at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, at the Moon & Sixpence cafe at Lakeside, Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, and Sam Read in Grasmere.

You can also order by post instantly here

The latest book is Secrets of the Lost Kingdom, available here: