The 1,000-year-old puzzle of Cumbria’s Viking cross

Norse refugees from an Irish battle in 902 AD erected the enigmatic 15-foot Gosforth Cross in their new home. The bafflingly equivocal work celebrates abandoning Paganism for Christianity. Possibly.

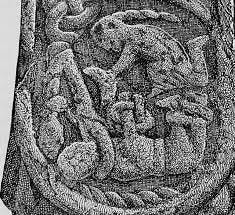

A slender fifteen-foot shaft of ruddy sandstone stands in the middle of a graveyard about two miles from the Cumbrian coast. It is covered with mysterious, some might say crazily interlaced, carvings of men wrestling with giants and demons. When you look at it from a distance, it looks Christian. Get nearer and it looks Pagan. Close up, it looks Christian again. Or does it? It’s weird.

The richly ornamented Gosforth Cross looks oversized as it towers over rows of conventional 18th century gravestones in the grounds of St Mary’s church, as if some ancient gardener had been too liberal with the fertiliser. But its incongruous size is not the only remarkable aspect of this piece of masonry - for one thing it has stood in the same place for 1,200 years and the people who put it there were not actually Christian.

So who created this mysterious monument smothered in pagan imagery, why did they do so and what the heck does it all mean?

These were some of the questions on the minds of two learned Victorian gentlemen who arrived in the churchyard on a dull wet day in 1881, determined to decode what they suspected was the inarticulate speech of the Viking heart.

Dr Charles Arundel Parker, an obstetrician, was with his friend the burly, bearded Reverend William Slater Calverley, vicar of St. Kentigern's Church in Aspatria. They may have seemed unassuming local amateurs to their acquaintances. But through diligent study and painstaking scrutiny they had become extraordinary antiquarians (a grand word meaning someone who studies old things). Their discovery changed the history of Britain. Weeks of pouring rain had softened the lichens that then filled every hollow and divot on surface of the enigmatic shaft.

The haut-bourgeois pair watched as Dr Parker’s coachman climbed a stepladder and gingerly scrubbed the masonry with a wet brush. The first section he uncovered was the triquetra, a symmetrical triangular ornament of three interlaced arcs decorating the head of the cross, a religious symbol adapted from ancient Pagan Celtic images.

Gradually, with each swish of the brush a visual record of one of the greatest cultural transformations in English history emerged from under the mossy camouflage. Depictions were uncovered of obscure Scandinavian sagas and Norse mythology apparently hinting at parallels with the Biblical Apocalypse and Crucifixion of Christ.

This story in stone was soon recognised as one of the greatest works of art of its type in Europe. But what on earth did it all mean? Well, frankly, the interpretation of the equivocal scenes on the four faces of the shaft has provoked a fierce debate that may never end. Sure, the stone monument clearly depicts figures in various scenes from the cycle of Norse myths called Ragnarok. This translates roughly as “twilight of the gods” or Gotterdammerung, the violent destruction of god and man as a prelude to an uncanny regeneration of human life on earth.

This was a very exciting discovery for our two antiquarians. It came only six years after Wagner caused a European sensation with the first performance of his Ring cycle based on the Ragnarok myth. Until Victoria's reign, Vikings were portrayed as purely bloodthirsty and violent. But perceptions were changing. Aided partly by the popular success of the haunting illustrations of Wagner’s libretto by the English book illustrator Arthur Rackham, Vikings were increasingly seen as fine representatives of the old northern virtues of boldness, honour and enterprise at the heart of British nationhood.

A consensus was growing among conservative intellectuals that Viking blood flowed in Victorian Britain’s veins, and that the time had come to celebrate this as an alternative to the “left-wing” rationalism that “caused” the French revolution.

The story of Ragnarok was dear to the almost entirely illiterate Vikings who began to colonise the west coast of Cumbria a thousand years ago. It tells how the world will end in an apocalyptic midwinter battle between the gods that destroys the planet, submerges it under water and how the world will ultimately recover and be repopulated by two human survivors. Our two Victorian antiquaries believed they could see parallels between the Viking imagery appearing on the Gosforth cross and the Christian story of Noah’s flood, Adam and Eve and the Apocalyptic destruction of the world in Revelation, the last book of the Bible.

On closer examination the correlations became more intriguing and ambiguous. One set of images appears to depict the death of Baldr. He is the god of light, joy and purity and also son of the most important Norse god, Odin. His demise perhaps reflects the crucifixion of Christ. The Norse goddess Nanna, who represents joy and devotional love, could parallel Mary Magdalene’s role. Then the cunning and mischievous snake god, Loki, is shown being bound just as Satan was by the Christian God. Hod, the blind Norse god, (another one of Odin’s sons) is shown being tricked by Loki into shooting the mistletoe arrow that slayed the otherwise invulnerable Baldr.

It also shows the battle Odin has with the charred fire giant Surtr, which perhaps echoes how Christ ultimately conquers the Devil. Then at the base of the cross is the mysterious Yggsdrasil, traditionally believed to be an enormous ash tree. In fact, it is more likely the long-living yew, a tree which has the strange ability to regenerate itself from apparently dead roots. This mystic tree’s branches link the nine realms of the cosmos symbolising the cycle of birth, growth, death, and rebirth just like the Biblical Tree of Life.

So, how did this extraordinary artefact get there?

Well, we know from the Annals of Ulster, a medieval chronicle written by monks of Belle Isle on Lough Erne, that in 902 AD an enclave of Viking entrepreneur-warriors was bloodily ejected from Dublin. The Scandinavians had founded and inhabited this prosperous slaving port for a century.

But two envious neighbouring Irish kings Cerball mac Muirecáin, king of Leinster, and Máel Findia mac Flannacáin, king of Brega became fed up of the Vikings’ constant raids on the interior to capture fresh slaves. Many wealthy Viking aristocrats, known as jarls, their battle-weary middle-class followers or karls and their slaves known as thralls took refuge from the slaughter by sailing for the Cumbrian coast. The Annals said they arrived in Britain “half dead” after the conflict.

They sailed up in several slender, 60-foot longboats, each traditionally manned by at least 25 fully-armed helmeted warriors. The personal grooming kits Vikings carried suggested in better times many had shoulder-length hair, moustaches and neatly trimmed beards. These refugees began a cautious but ultimately influential colonisation of the place we now know as Cumbria. It must be remembered that at that time there was no such place as England or even a notion of a “nation”. The idea of a county was also foreign to the time and there was no concept of invasion either.

Unlike the violent and devastating Viking attack and robbery of the church at Lindisfarne Island in 793 AD that sent a shockwave through Europe, there is little or no evidence the Vikings ever “raided” Cumbria. The word “viking” referred to an activity by a tiny minority of people famous for their violence rather than the largely peaceful Norse population as a whole. No, the Viking “invasion” of Cumbria was more a case of chequebook than chainmail. The district around Whitehaven is called “Copeland” because that is Old Norse for “bought land”.

They came in three waves. The wealthiest first ripple acquired some of the richest land on the western coastal plane and north Westmorland. In the second wave middle-income Vikings took less good lowland sites and the third wave consisted of poorer shepherds who settled for “waste” land high on the fells.

Until recently archaeological evidence for this Viking presence in Cumbria was very thin. Even so, Victorian antiquarians assumed the Scandinavians came in large numbers. This deduction rested on the widespread evidence of Norse place names such as Keswick, Whitehaven, Ravenglass, Silloth, Ulverston, Ambleside. The impression was reinforced by the fact that several Norse words entered the local dialect such as fjall - which means “mountain” or fell, dalr - which means “valley” or dale and bekkr which means “stream” or beck. But the lack of material signs of Norse people actually living on the ground troubled the more intelligent experts, such as WG Collingwood. No evidence of any Scandinavian houses has been found, for example.

But this did not stop prominent Victorian antiquarians such as the famous cleric, writer and conservationist Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley jumping to the conclusion that Cumbrians, and possibly most of the British, were descended from the Viking incomers. The sight of hunky Statesman farmers with their blue eyes and fierce independence striding through Keswick marketplace was enough evidence for him. Of course, Rawnsley’s type of racial bluster ended up being used for infamous ends later in the 20th century.

Even the cautious Collingwood was seduced by the notion. He depicted the Norse settlers in his 1895 novel “Thorstein of the Mere,” as the superior race among Lake District dwellers whose bloodlines spread to dominate the local population. The story is about a Viking boy who discovers Coniston lake. The book was a favourite of Arthur Ransome, author of Swallows & Amazons. But in fact genetic material does not descend in the way Collingwood speculated.

Recently, mainly thanks to the indefatigable efforts of metal detectorists, the tiny trickle of evidence confirming the Viking presence in Cumbria has become a stream. In 2011 a hoard of 92 pieces of Viking silver turned up at Stainton. The Penrith Hoard of 10th century silver Penannular brooches was mostly found in 1989 at Flusco Pike, near Penrith and a merchant's lead weight was dug up in 2006 on the Furness Peninsula, for example.

But the work of archaeologists has since proved there were never enough Vikings to challenge the power of existing Cumbrian kings. Vikings never had the numbers to swamp the population of indigenous Celts who had arrived at least 4,000 years before they did. Anglo-Saxons also gradually filtered into Cumbria later too. So, far from being the superior race, the Viking colony had to find a way to rub along with the existing inhabitants.

They had to ensure their old Pagan traditions interacted peacefully with those of the natives. And the natives were predominantly Christian. When the Vikings first arrived the trinity, saints and the multitude of angels the locals spoke of must have seemed interchangeable with their Norse deities. As a people used to having many gods, it might have seemed easy enough to add a few more. But fairly soon the exclusive nature of the Christian god must have become very apparent to the Vikings.

The 10th Century Christian Church was stepping up its efforts to convert the incomers, partly by ruthlessly appropriating Norse rituals. For example, Yule was the name of a winter festival that occurred in December and January on the pre-Christian Germanic lunar calendar. The church deliberately decided to celebrate the birth of the Lord Jesus Christ at that time with a 12-day feast, often called Epiphany or the Feast of the Nativity in order to absorb the Norse event. Over time the season became known as Christmas.

So we might assume the Gosforth Cross was simply intended to show the triumph of Christ over these silly old pagan gods and myths - after all the top of the monument is a cross seemingly trumpeting the supremacy of Christianity. But it isn’t so. The Gosforth Cross is an apocalyptic piece of art that has much more in common with the Pagan roots of the incoming Vikings than the Christians who lived nearby. The astonishing artefact doesn’t commit wholeheartedly either to Paganism or to Christ.

Maybe it performs a function something more like a flag planted in England, a land that the Vikings intend to make their own. It lovingly reproduces the myths and legends that their families grew up with in the form of an iconic stone obelisk that they intended never to decay. But it also nods towards the dominant Christian culture at a time when Vikings in England and across Scandinavia were converting to Christianity in large numbers.

Eventually, history tells us, the need to fit in overcame tradition and the Cumbrian Vikings became at least outwardly conforming Christians. The Gosforth Cross is perhaps a wistful and ambiguous memorial to the twilight of the Norse gods at a time when the Old Norse culture seemed

about to vanish from their lives. But these Pagan gods did not go quietly and, in a sense, perhaps they never did.

This is merely an extract. You can read the rest of this fascinating piece about England’s first true industry in a new book called Huge & Mighty Forms. You can buy the book at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, at the Moon & Sixpence cafe at Lakeside, Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, and Sam Read in Grasmere.

Or instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/Huge___Mighty/p5921133_20075309.aspx