Q: Why does the Lake District lack trees? A: Because prehistoric Cumbrians chopped them down (except the yews)

Gnarled, stunted and often more than 1,000 years old, how come yews still pepper the fell sides and churchyards when more beautiful species got brutally erased?

One of the most mistaken ideas about Cumbria is that it had a stone age. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Yes, of course, they have found 2,400 highly polished Langdale axes. There are fifty stone circles in Cumbria. Thousands of flint tools have also turned up. All this has made people think Neolithic Cumbria was rather rock-based.

But it would be much more accurate to rename the period between 10,000 BC and 2,200 BC “The Wood Age.” Prehistoric people made more things out of wood than stone. They also cleared the fells of trees to make room for farms and sheep. The deforestation of Cumbria was complete at least 1,000 years before the Romans arrived. But the ancient Cumbrians made an exception for at least one species.

One clue to what really happened is: there are hundreds of ancient yew trees across Cumbrian fell sides. You may ask why are there so many yews when the Lake District is famously bare of trees?

To understand this paradox, we first need to acknowledge that wood was one of early mankind’s most valuable and important raw materials. It gave prehistoric people shelter, heat, tools and weapons vital for survival.

Yet if you read most books about archaeology there are pages and pages about stone, bronze and iron finds, while wood hardly ever gets a mention. This is odd because most metal or stone tools needed a wooden part to work.

The reason why the archaeologists don’t talk about wood much is pretty obvious. They haven’t found much of it. Wood decays. If left outside, it soon gets broken and crumbles to nothing. It burns to ashes and it rots in the soil. It will only survive under the most extreme circumstances: if it gets buried in a wet place without the oxygen wood-eating microbes need.

One of those rare situations occurred in Cumbria. In 1871, a farmer dug a trench and drained the water from Ehenside Tarn. An entire Neolithic village emerged from under the water.

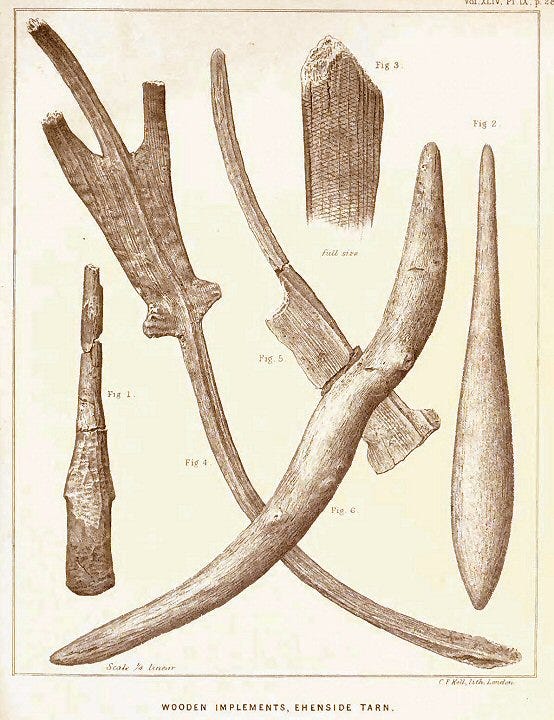

A host of wooden items that archaeologists had never seen before emerged from under the water at Ehenside Tarn

A host of items that archaeologists had never seen before emerged. There was a dugout wooden canoe with a wooden paddle, a wooden throwing stick for catching game, a mysterious fork made of oak, two menacing-looking clubs made of beech, a digging stick and greenstone axes in various stages of polishing, some complete with beech hafts.

So, what has this got to do with the yew trees mentioned earlier? Well, because Neolithic people were compelled to chop down some types of tree and not others.

At the start of the Neolithic era, Cumbria was densely forested. Then, around 6,000 BC people switched from hunting and gathering to farming. Pollen traces show people cleared forests to herd sheep, graze cattle and grow grains. By about 1,000 BC, just 13 per cent of Britain was wooded, about the same as today. Forest cover in the Lake District is about 12 per cent.

But as the fellsides were denuded of trees a few species were spared. That is why the fells are today peppered with twisted, stunted but healthy-looking yews. Often these yews grow in extremely unpromising places such as soilless scree slopes and steep precipices. How is it that they have survived the hazards of time, arctic levels of cold and lack of nutrition?

The answer is that ancient people valued them immensely. Yew wood was renowned in agricultural lore for being as hard as iron. Robert Hardy, the internationally famous expert on the longbow, thinks the best material for making the weapon is the exceptionally close-grained wood produced in the Cumbrian mountains, home of the country’s slowest-growing yews. A single-piece Neolithic yew bow dating back to 4,000 BC was found at Moffat in Scotland, eighty miles from Borrowdale.

Critics might object that there is very little evidence that any early humans lived in the Lake District uplands. But as the 1953 handbook “Archaeology in Britain” put it, traces of their homes were probably wiped away because the prehistoric people cut down the birches. This resulted in “the remains being covered with peat, hill-wash etc., owing to the removal of the tree cover.”

Food supplies was another factor. The honey-sweet, scarlet-coloured arils that appear on yew trees each autumn were an important food source for early humans. And then there is religion. Yews have always had an aura of religious mystery around them. Male yews are renowned for producing copious amounts of pollen in the spring, so much so that the trees can appear to be surrounded by clouds of woodsmoke. This phenomenon could be one of the sources for the myth of the burning bush symbolising God’s miraculous energy. Yew pollen is also reputed to be hallucinogenic, which was another attraction.

The yew came to symbolise death and resurrection in Celtic culture

Drooping branches of old yew trees can root and form new trunks where they touch the ground. Thus, the yew came to symbolise death and resurrection in Celtic culture. Neolithic people planted them next to their burial mounds. The Viking sacred tree, Ydddragsill, the centre of the Norse cosmos, was a yew.

So, when Christianity came to Britain the Catholic Church wanted to neutralise these powerful pagan sites by taking them over In 601, Pope Gregory decreed that places of pagan worship should be converted into Christian churches. That’s why there are often yews in churchyards.

This, for example, may explain the survival of the “Fraternal Four” Borrowdale Yews, made famous in 1803 in a poem by William Wordsworth. The trees, which are at least 1,500 years old, and quite probably predate Jesus Christ, are still growing near the church in Seathwaite.

—

Read more about the the strange survival of Borrowdale’s ‘life and death’ trees in a new book called Secrets of the lost Kingdom.

You can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop on Main Street, Cockermouth. They are also available at the Moon and Sixpence, Lakeside, Keswick. You can get them at Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, or Sam Read in Grasmere.

Or you can buy it instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/secrets-of-the-lost-kingdom

Understood. However, the trees are being cut down in Ennerdale because of Phytophthora larch disease. The cull finished in March and over the next two years they are going to replace them with native species, as I understand things.

Been destroyed now with all the harvesting. It looks awful up here. Especially around whinslatter and Ennerdale.