Purple crystals found in Cumbrian mud rewrite Roman history

Gem discovery adds to evidence that Emperor Septimius Severus built lavish bath complex for wife during three-year stay at Carlisle

A mysterious chunk of rock with reddish-purple crystals inside is causing intense excitement amid the mud, grime and debris of an archaeological dig in Carlisle.

Experts believe the gems, possibly amethysts imported from ancient Siberia, were ground up and made into a purple pigment by artists who came to the north west of England more than 1,800 ago.

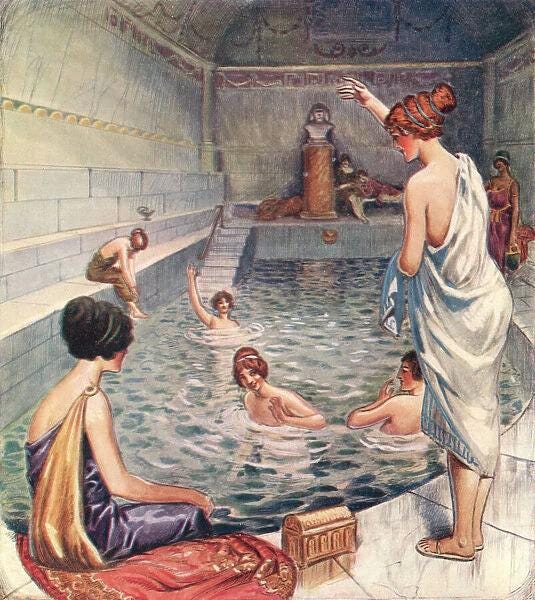

The crystals were unearthed on the site of the largest Roman building ever found on Hadrian’s Wall. In 2017 a flood exposed extensive ancient remains beside Carlisle Cricket club. Archaeologists who initially expected to find little more there than architectural rubbish have since uncovered an astonishingly lavish 160-foot square bathhouse.

The archaeologists say the discoveries not only re-write the Roman history of Cumbria, but they are also of international significance.

The two-story building features unique monumental sculptures. Its vaulted ceilings were built with lightweight North African terracotta tube technology. Only four similar examples exist in Britain.

The discovery of the purple crystals is potentially momentous. It adds to the mounting evidence that the luxurious baths complex was built by Emperor Septimius Severus for his wife Julia Domna when he made the city his summer military base between 208 AD and 2011 AD.

It is now believed he led a military onslaught by 50,000 legionaries against troublesome Caledonian tribes from Carlisle. In the past it was assumed the emperor led his troops from York.

Records show this was the biggest military action ever to take place on British soil, right up to the present day. Severus’ needed to be present at Carlisle because it was the base of the Ala Petriana, the crack Roman cavalry regiment based at Stanwix fort, easily the largest body of horse warriors on Hadrian’s Wall.

The elite 1,000-strong unit was the most feared fighting force in Britain. The baths complex is less than 500 yards from the fort. Military strategists say Severus needed to launch his attack there to avoid being outflanked by the Caledonians who traditionally invaded the south via the ford on the west side of the country over the local river Eden.

Only Emperors were allowed to use purple. It was the official symbol of the extreme power and wealth belonging to the ruler of the world.

The Roman reverence for purple stemmed from its rarity, costliness and the difficulty involved in making it. Tyrian or Imperial purple takes its name from the dye that was produced in the coastal city of Tyre in what is now Lebanon.

The source of the colorant was the mucus produced by predatory sea snails found in the Mediterranean Sea. Thousands of snails were needed to make one ounce. A pound of the substance cost about half a Roman soldier’s yearly wages or the price of a diamond engagement ring today. The dye was used to colour the Emperor’s clothes.

An alternative source of reddish-purple pigment for items other than clothes is said to be powdered amethyst crystals which craftspeople can buy today. When mixed with wax or oil it made a fine quality paint that could be applied to a woman’s nails or, for example, furniture in a process that is still used. When allowed to dry, the paint can be buffed to a deep shine using a cloth impregnated with candle ash as a delicate abrasive.

The discovery of the crystals was revealed by Frank Giecco, from Wardell Archaeology, who is leading the dig in Carlisle. He told Series 11 of the BBC’s Digging for Britain: “We think it’s pigment. It’s up for debate. They are not quartz but we have yet to pin down what it is.

“You can’t get any more imperial than that because only the Emperor could wear it. Septimius Severus came up with his wife and children so the north of England would have been the centre of the Roman Empire.”

The crystals are undergoing scientific analysis along with hundreds of other finds. These include dozens of intaglio gems made of amethyst, jasper and carnelian delicately carved with the images of gods. Scientists say the intaglios fell from the rings worn by wealthy Roman bathers - and their children - when vegetable glue melted and the tiny stones were washed into the drains.

Controversy is also growing around two of the other extraordinary items extracted from the mud - a pair of huge carved stone heads. Mr Giecco described them as “weird and mind-blowing” sculptures created in a “very strange style” unlike anything found before in Roman Britain.

Each one measures more than two feet high but they may have come from statues originally fifteen feet high. One head seems to be female. Her hair tied in thick, wavy plaits, the style which Julia Domna wears in many statues and busts carved at the time. The other in a darker red sandstone believed to have come from St Bees. It features a more tousled hairdo and commanding expression. The heads are not carved with great skill; you can see the sculptor’s tool marks and they were clearly designed to be seen from the front only. But they certainly would have been very a striking sight mounted six feet up on the wall of the building.

Opinion is divided over who the heads represent. Dozens of tiles excavated from the site bear the initials “IMP” which indicates the baths were built at the personal command of the emperor. So, many people believe the statues depict the emperor and his wife.

Others are more circumspect, arguing the heads resemble classical Roman theatrical masks depicting gods designed to scare away evil spirits at a time when bathers are naked and vulnerable in the baths.

If this theory is correct, they might represent the goddess of luck, Fortuna, and maybe Mars, the god of war, both of which would be appropriate deities for an emperor about to embark on a risky military action.

Yet the Carlisle heads do not resemble the typical open-mouthed Roman masks that depict comedy and tragedy. Such masks are usually made of terracotta and would be light enough for an actor to carry around a stage, whereas the Carlisle heads are very weighty blocks of stone. Also, the Carlisle bathhouse does not appear to have been a theatre.

Whatever the final verdict, it is clear the Carlisle boathouse excavation has vastly increased the importance of Cumbria in Roman history.

This is an extract based on a chapter in a new book called The Trophy at the End of the World. You can buy it instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/the-trophy-at-the-end-of-the-world

Or you can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick or Carlisle and Sam Read in Grasmere.