Merlin was a Cumbrian

The figure of the wizard, teacher and guardian of legendary King Arthur was based on a noble who became a forest-dwelling wild man after a horrendous Dark Age battle nine miles north of Carlisle.

The figure of Merlin, the great wizard and central character in the legend of King Arthur, was based on a real man from Dark Age Cumbria, according to the latest research.

Clues to the real origin of the magician, teacher and guardian of Britain’s most famous ruler are hidden in texts dating back over a thousand years.

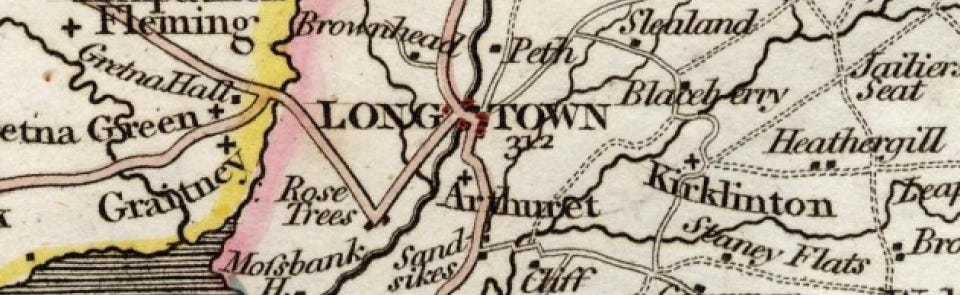

The elusive figure is believed to have been a participant in the Battle of Arfderydd, or Arthuret, near Longtown, Cumberland, nine miles north of Carlisle in 573 AD.

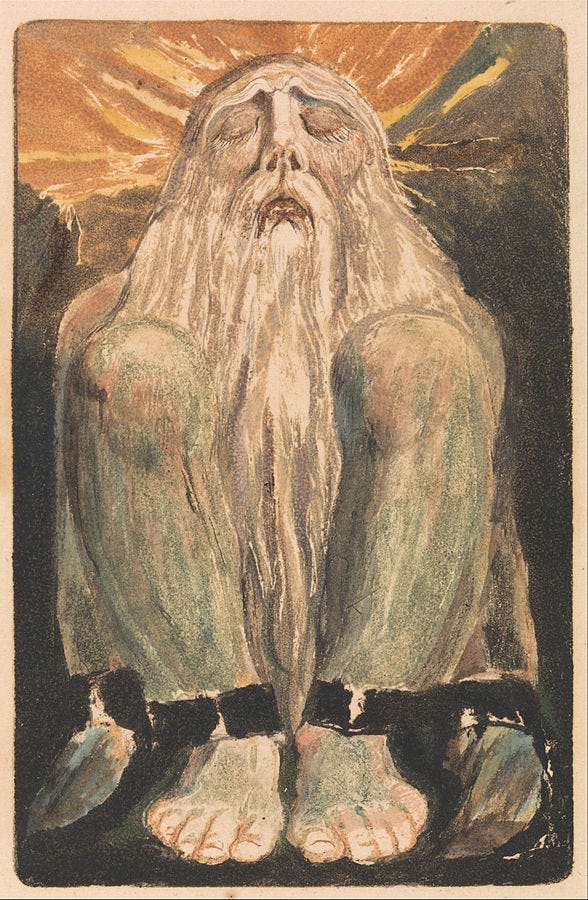

So appalling was the slaughter in this military clash that the Merlin-figure was overcome by grief and horror. He fled the battlefield to seek solitude in the forest where he was believed to have developed uncanny powers of prophecy.

On these foundations, as the brilliant historian Tim Clarkson has shown, poets over the centuries built the mythical literary character of Merlin, a powerful magician, shape-shifter and seer.

Any mention of Merlin automatically brings up the name of Arthur, the Once and Future King to whom the druid-like sorcerer is popularly believed to be indissolubly connected. But in fact, there is no credible evidence of Arthur having links to the north-west. In the case of Merlin, the opposite is the case: this piece will show that the original model for the legendary wizard was a real Cumbrian.

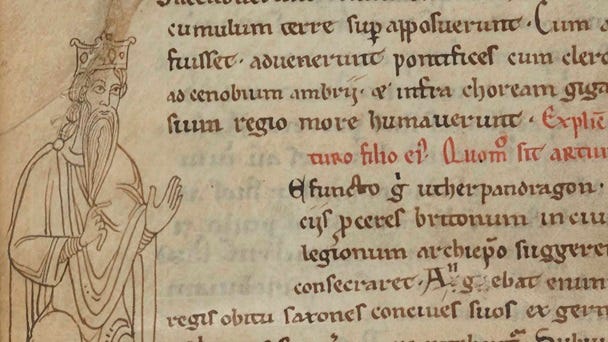

The popular conception of Merlin derives from a twelfth century work written by a Welsh cleric called Geoffrey of Monmouth. It was called the History of the Kings of Britain, published around 1136, and it became a medieval bestseller. It was the first of two major books by Geoffrey that featured the figure of Merlin. The second one came a dozen years later and was called ‘Vita Merlini’ (‘Life of Merlin’). Each one presented the wizard as a rather different character.

Medieval readers of both books would have realised Geoffrey was writing pseudo-history in which fact and legend are skilfully interwoven.

But the “History” in particular offered an exciting and colourful account of two thousand years of political intrigue. It was eagerly received by his readers across Europe and therefore Geoffrey’s impact on the whole of medieval literature cannot be overstated.

In the first book, Merlin enters Geoffrey’s story at the point when the British King Vortigern has become angry. The foundations of the new fortress he was trying to build kept disappearing each night. The king’s advisers told him the only way to thwart the mystical forces gobbling the stonework was to sprinkle the blood of a fatherless child on the site, a human sacrifice believed to be a normal part of Celtic ritual.

The king’s soldiers found a suitable sacrifice in Carmarthen in Wales and dragged the boy before Vortigern. But Merlin stepped in to save the child by declaring the real problem was a fight between a red and a white dragon in a subterranean pool under the fortress’s cellars.

The red one, he explained, were the Britons, and the white their Saxon foes. Merlin then prophesied the Saxons would eventually conquer most of Britain (which of course happened).

Geoffrey credited Merlin with moving Stonehenge from Ireland to Britain and gave him a role in Arthurian legend. He enabled Arthur’s father Uther Pendragon to sleep with Igerna, a Cornish noblewoman, another man’s wife. It was through this deceit that Arthur was conceived. However, Merlin does not appear in the largest section of the book, concerning Arthur’s later career. The prophesies of Merlin that Geoffrey recorded were widely discussed across Europe.

In the mid 1150s the Norman poet Wace adapted the Latin translation of Geoffrey’s history to create the Roman de Brut (‘Romance of Brutus), a Christianised history full of tales of chivalry and country love that added significant new elements to the Arthur myth, such as the Round Table.

Around the year 1200, the Burgundian poet Robert de Boron deepened the Christian content. He used Wace’s version of Merlin as the basis for his own narrative poem ‘Merlin’ which formed the second part of a trilogy on the legend of the Holy Grail, traditionally thought to be the cup that Jesus Christ drank from at the Last Supper and that Joseph of Arimathea used to collect Jesus's blood at his crucifixion.

Boron also gave Merlin a more central role in Arthur’s story. The wizard becomes the future king’s mentor and he appears as more of a trickster and shapeshifter. Crucially in this version, Arthur’s father Uther orders the Round Table to be made and Boron introduced the magical sword firmly embedded in an anvil on a block of stone, fixed there by Merlin’s sorcery.

The wizard caught the imagination of several anonymous authors. French versions of the Merlin tale became hugely popular across Europe.

Merlin plays a significant, though slightly diminished, role in Sir Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur. His 1470 version was written during a stint in Newgate Prison after Malory was convicted of plotting Edward IV’s overthrow. Malory introduced Arthur as the chivalric king, his unfaithful wife Guinevere, Sir Lancelot of the Lake, Sir Gawain and the other knights of the Round Table with Merlin relegated to his modern guise, wise counsellor and minster, rather than his earlier persona as mighty seer and powerful sorcerer.

But, as noted earlier, this was not the only Merlin book that came from Geoffrey’s pen. His ‘Vita Merlini’ (‘Life of Merlin’) never attracted the acclaim of the earlier one but it is vital for understanding where the character came from.

Geoffrey’s second work about the wizard was produced probably in around 1150. It presented a different Merlin, reinvesting him with his full powers as a prophet and sorcerer and moved the geographical setting from Wales to the Kingdom of Cumbria.

The Vita appeared probably in around 1150. It presented a different Merlin, reinvesting him with his full powers as a prophet and sorcerer and with the geographical setting moved from Wales to the Kingdom of Cumbria. Geoffrey did not do this on a whim. The change came about because he was working from a different source with its origins in the north.

The first Merlin had served the King of Dyfed in South Wales and chief seer and law-giver. But the new one moved northward to support the British leadership in a landmark war with the Scots. Merlin, wearing a gold torc of authority, accompanied the paramount leader of the Britons and ruler of the north Welsh, King Peredur.

The king was a member of the Coeling dynasty that had ruled Northern England since the departure of the Romans. Peredur was a cousin of Urien, the sixth century king of Rheged, the land we now know as Cumbria and a hero to the Cumbrians. Against him was Guennolous, the ruler of Scotland.

The ensuing clash near Longtown in Cumbria was a real historical event. It turned into a grotesque bloodbath and lasted six weeks. Three hundred men were killed and buried nearby. The name Arthuret has nothing to do with King Arthur. The word comes from the Welsh word Arfderydd which can be translated as “scorched by arms”.

Peredur’s brothers were slain during a brave charge through the Scottish line. Witnessing so much carnage proved too much for Merlin. Driven to distraction by sorrow and terror he broke down and wept for the young warriors cut down in their prime. The bloodletting ended when the Britons finally drove the Scots from the field.

But Merlin was unconsolable. “He threw dust upon his hair, tore his clothes and lay prostrate on the ground, rolling to and fro,”

But Merlin was unconsolable. “He threw dust upon his hair, tore his clothes and lay prostrate on the ground, rolling to and fro,” Geoffrey wrote. The wizard would take no comfort from anyone, not even Peredur and his victorious commanders. Merlin manifested a “strange madness”.

For a whole summer he sought solitude among the Cumbrian trees, living as a wild creature, foraging for roots and berries “lurking like a wild thing,” Geoffrey added. As winter came and Merlin could no longer pick food from the branches the Britons sent out a search party and found him on top of a mountain. Told that his wife, Guendolena, was pining for him, Merlin agreed to leave the forest.

He was greeted by great crowds of cheering nobles whose noise pitched him straight back into madness. Rodarch, King of the Cumbrians, ordered that he be imprisoned for his own safety. Eventually he was allowed to return to the forest where he made a whole lot more prophesies (which the readers know are all accurate because the events have already happened).

According to Geoffrey, King Arthur’s entire career unfolds during Merlin’s leafy exile. Uther’s illegitimate son succeeds to the throne by pulling the sword Merlin fixed there from the stone. He is betrayed by his wife, is mortally wounded and is borne to the Fortunate Island.

Throughout all this Merlin remains in the forest and plays no part in Arthur’s adult career. Then one day Merlin’s conversation with Urien’s court poet Taliesin was interrupted by the news that a spring had appeared at the base of a nearby mountain. When Merlin drank from it, his madness miraculously disappeared.

This second version of Merlin is distinctly different in one key respect - the original Merlin remains in Wales while the new one migrates to Cumbria. But why? The answer is: because Geoffrey’s new material came from northern sources. The research shows that the story of the wild man in the forest originated after a real Cumbrian noble, whose mind was turned by the horrors of the battle near Arthuret in 573 AD, fled to the forest.

Sign up to read on.

This piece is from a forthcoming book. You can read the rest by signing up. Or you can get more like it by buying one of my other books here:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.