If Cumbria collapsed when the Romans quit, who made this masterpiece?

Some historians argue that without access to classical learning, Cumbria plunged into a six-hundred-year Dark Age. But how come it helped make the glorious Lindisfarne Gospels?

It was the last thing a Roman soldier wanted to see coming out of the mist at dawn on a bleak northern hillside.

Hundreds of blue-painted warriors, some stark naked and screaming like animals. They were bearing down on Birdoswald fort, brandishing one-handed axes.

This was the horrifying sight facing Hadrian’s Own Dacians, the military unit occupying the riverside fortress on Hadrian’s Wall that morning in 367AD.

The attack was the start of a year-long onslaught against the Romans launched by massed armies of Celts, Saxons, Scots and Irish. It is said to have left Birdoswald, and other forts devastated.

The Romans were to remember the huge raid rather self-pityingly as the “Great Barbarian Conspiracy”. It happened in the place we now know as Cumbria, but which the miserable Imperial troops called the world’s end.

Pessimistic Romans portrayed it as the beginning of the end of empire’s rule over Britannia. They were right.

Within forty years Imperial troops departed the islands for good. The failure to defend the border was a catastrophe for Rome. It showed the Imperial system was defunct, outdated, finished. Blinded by its pompous self-regard, fooled by misplaced contempt for its opponents and riven with internal rivalries, Rome was incapable of learning that there were other ways of doing things.

According to the traditional story, the retreat of Rome from Britain instantly plunged Cumbria into the Dark Ages. Complete economic, intellectual, and cultural collapse ensued, allegedly. Due to its remoteness, mountainous terrain and stubborn refusal to fully embrace the advantages of Roman civilisation, Cumbria, it is argued, suffered a greater cultural, demographic and spiritual loss than much of the rest of Britain.

Deprived of the light of Classical learning, its people were plunged into a six-hundred-year long ordeal of ignorance, backwardness, violence and superstition, many academics say.

For the sixth-century British monk Gildas, the end of Roman Britain was sudden, dramatic and apocalyptic, adding: “The barbarians drive us to the sea”.

The author of 2022’s Lost Realms, Thomas Williams, agrees the country suffered the “trauma of collapse,” although he adds some Dark Age kingdoms started to do pretty well until the Anglo-Saxons turned up.

But one of Britain’s most influential historians, Professor Frank Stenton, began his seminal work, Anglo-Saxon England, published in 1943, with the words: “Between the end of the Roman government in Britain and the emergence of the earliest English kingdoms there stretches a long period of which history cannot be written.”

By earliest English Kingdoms he means East Anglia, Mercia, Northumbria, and Wessex which emerged in 829 and became united as England in 929.

Stenton’s claim is particularly astonishing: without the influence of Latin civilisation, he implies, nothing happened that was worth recording in Cumbria for six hundred years.

He claims that the withdrawal of the rich, oppressive, and superficially well-organised Romans meant that culture and sophistication disappeared from Cumbria until it was re-imported by another batch of “superior” foreigners, the Germanic tribes of northern Europe, half a millennium later. The Germanic hordes had cultural and commercial contacts with Rome and the argument is that by invading Britain they brought back key aspects of classical civilisation.

Stenton was one of the foremost British intellectuals of the 20th Century and a man of enormous learning. But, unfortunately, his influence has downgraded the importance of the very period when Celtic culture had its heyday in Britain and asserts that that it had no worthwhile legacy to put in a history book.

This has fed the myth that Britain is an Anglo-Saxon country with a culture derived from north Germany, and that Celtic influence was at best marginal if it existed at all. The only trouble with this view is that it is nonsense.

After the Romans quit, Britain became divided into thirty separate Celtic Dark Age kingdoms.

They included Hen Ogledd (The Old North), Elmet (West Riding of Yorkshire), Gododdin (South East Scotland and Northumberland), Rheged (Cumbria) and Strathclyde (Southern Scotland and Northern England).

The Anglo-Saxons gradually started arriving around 450 AD (there was no “invasion”). At most it is estimated the influx added a total of 250,000 people over a period of years to an existing population of up to two million, so the Anglo-Saxons were outnumbered by eight to one by Celts.

The Anglo-Saxon kings eventually seized power, but the vast majority of their subjects were Celts – not a single ethnic group but people who spoke Celtic languages. DNA evidence suggests these Celts were the indigenous inhabitants who migrated from a warm refuge in Iberia after the last ice age, 10,000 years before.

In England today, 64 per cent of people could trace their ancestry back to the Celts. The Celts were the original Britons while the Anglo-Saxons were Germans.

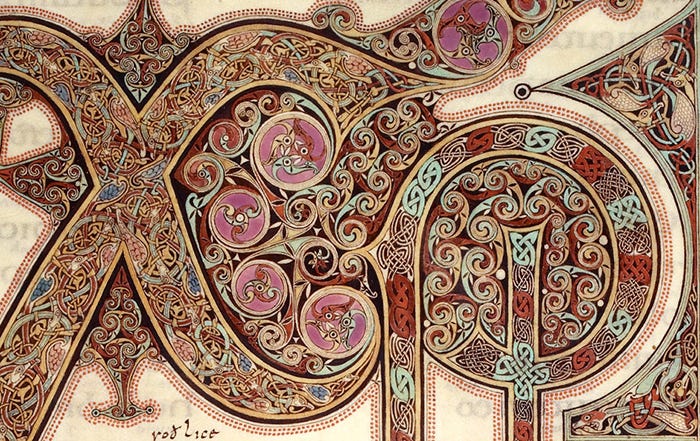

But if Stenton implies the Celts were nullities for six centuries, how come they helped produce the most spectacular cultural artefact of the early Middle Ages: the Lindisfarne Gospels?

This fabulous, illustrated manuscript was finished around 700 AD. It brilliantly combines influences from several sources. The design is dominated by the complex and swirling vegetal imagery of Celtic art with its scrolls, knots, intricate twisting patterns, dragons, and crosses drawing on traditions dating back to 1,200 BC. The pages also feature German animal ornament and Mediterranean influences, particularly in the magnificent pages that look like oriental carpets.

The existence of this treasure clearly indicates that, despite Stenton’s contention that nothing historically noteworthy happened, there was a powerful tradition of Christian artistic endeavour, learning and philosophic reflection in early Medieval Cumbria and the north.

Some people argue that the Lindisfarne Gospels is an Anglo-Saxon artwork because it came out of a Northumbrian monastery on Holy Island. But the squabbling and fratricidal Northumbrian royal family had been mired in Norse paganism - worshipping deities such as Woden, Thunor, Tiw and Frig - until 616 AD. They had adopted Christianity (off and on) only eighty years before the Gospels were produced.

So, the Anglo-Saxons borrowed Celtic culture in order to benefit from its reflected prestige. Yet, despite this, some modern academics, trained to see Greece and Rome as the fount of civilisation, still try to write the Celts out of history and insist on the primacy of classical culture.

This view still permeates official thinking. For example, one of the Government’s propaganda magazines was called “Britain.” It was produced by the advertising agency MotherLondon, the same one that was responsible for the bombastic “Great” advertising campaign designed to promote Britain’s tourism and trade.

The paper declared: “Technology, architecture, language, government, town planning – even a sense of national identity. The depth of the Roman influence on the British Isles was such that it survives to this day, seemingly unmatched by that of any of the invading forces that followed them.”

But what evidence is there for this?

Cumbria’s towns and villages were overwhelmingly created by Celts, Norse, Anglo-Saxons and Normans, not Romans. Roman grid plans are vanishingly rare in our towns – not even the former Roman City of London has one – and they are especially rare in the north. The Celtic language spoken in the place we now know as Cumbria was called “Cumbric.” It contained no Latin words to speak of. The Cumbrian dialect which replaced it in the 12thcentury is a melange of Celtic, Norse and Scots.

Yes, the roots of the official version of the English language we speak today do derive from the West German dialect of northern Europe as spoken in the Early Middle Ages. But this is not the whole story. The Germanic tongue the Anglo-Saxons brought with them was strewn with a complex system of word endings. Nouns for instance had three genders (masculine, neuter, feminine), two numbers (singular, plural), and five cases (nominative, accusative, genitive, dative, instrumental).

All these were stripped away by the indigenous Celts of Britannia. They were illiterate people who had no concept of academic grammar. They were the main speakers of the Germanic language simply because they were the overwhelming majority of the people. Without any hesitation, they made the Germanic tomgue conform to the pattern of Celtic which conveys meaning in an entirely different way - by word order.

Today, just under one third of our vocabulary is made up of Latin words, but they were brought in by the Normans along with a similar number of French words.

MotherLondon is wrong again about our government. The Romans had virtually no influence on it. Our Parliamentary tradition was established in 1215 with the signing of the Magna Carta: Britain’s governing system is not and has never been organised on the lines of a Roman-style dictatorship.

As for Rome’s famous technology, the truth is the empire was a copycat regime. Romans were not very innovative. The so-called Roman wheel was actually invented in Mesopotamia in 2,000 BC; stone-built roads were first developed in Ur, Iraq, in 6,500 BC; surveying was first recorded in Egypt in 3,000 BC; armour was invented by the Greeks in 1,400 BC as was the catapult in 400 BC.

Apart from some stone foundations, the most remarkable thing about the Roman culture is how little, not how much, trace it left behind in the north of England that is still influential in life today.

During the centuries of supposed tumult and disorder in Britain after the Romans went, the population of the place we now know as Cumbria did not decline – it continued to grow. Agriculture did not suffer either. It benefitted from Roman forts no longer confiscating a portion of the crop. Quite soon after their departure, as the sixth century cleric Gildas made clear in his polemical history “The Ruin of Britain,” the Romans came to be seen by the Britons they had colonised as having been an alien force imposed on the Island, not a source of “national identity.”

Traditional teaching has it that Christianity died out after the Romans left and a monk from Rome called Augustine brought it back to Britain in AD 597. But Christianity was present in Cumbria at least 200 years before that, during Roman times in the third century. It was introduced by tradesmen, immigrants and legionaries. There is increasing evidence that the religion continued to thrive as a force for learning, culture, and social organisation in the western parts of England thanks to the missionary efforts of St Ninian, St Kentigern (Mungo) and St Patrick. Oxford Professor of Archaeology Barry Cunliffe noted in his book Britain Begins there are hundreds of Celtic inscriptions in the west written in the ogham alphabet showing extensive contact between settlers and traders from western Britain and Ireland at this time, as they sailed back and forth across the Irish Sea. They “give us a sense that Christian leaders… played a very active role,” he wrote.

Solid evidence for Celtic Christianity’s flourishing was provided by a fourth century Roman altar at Maryport. It was re-cut with a Chi-rho symbol that superimposes the first two Greek characters spelling ‘Christ’. The symbol is one of the earliest known emblems of Christianity and it is likely to have been added after the Romans left. A drawing was made of the inscription in the 19th Century but, mysteriously, the stone itself has disappeared. There are other traces of Roman-era Christian gravestones in the town.

With the Romans gone, the area became known as the “Old North” whose praises were sung by the Welsh bards. At this time in history, the Britons and Welsh were seen as one people. They both spoke Cumbric, a language that is closely related to Old Welsh. All these facts contradict the traditional view that Cumbria descended into profound cultural darkness. There is no doubt the products of Roman international trade disappeared, the quality of pottery fell, items made of iron became scarce and imported luxuries, for the few who could afford them, became almost unobtainable.

But the ordinary Celts of Cumbria had benefitted very little from the Roman presence anyway, so they did not have all that much to lose. Very few luxury Roman goods found their way into the indigenous people’s roundhouses during the occupation, archaeology has shown. But material goods are not the totality of culture.

Unlike people in the south of Britannia, northern Celts never significantly embraced “Romanitas” or Roman-ness, nor were they invited to. But as the empire died, the Cumbrians were already plugged into the civilised and literate international system represented by the Celtic Christian Church. They converted to Christianity at least 215 years before the pagan Anglo-Saxons of Northumbria adopted the faith.

This is something that provoked the seventh century Jarrow-based historian Bede to bitter rage. In his book, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, Bede accused the Celts of a “crime” in failing to spread Christianity among the Anglo-Saxons.

As we will see, it was this vigorous Celtic tradition, not the Roman or Anglo-Saxon ones, that provided the driving cultural force behind the Lindisfarne Gospels. Yet, even today, the Gospels are treated with a curious lack of interest and pride by the public-school educated cultural establishment…

This is an extract based on a chapter from a new book, The Trophy at the End of the World. You can buy it instantly here:

: https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/the-trophy-at-the-end-of-the-world

Or you can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick or Carlisle and Sam Read in Grasmere.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.