How Vikings defeated by Alfred the Great colonised Cumbria instead

Blood-soaked Great Heathen Army destroyed Carlisle and murdered Celtic Christians, occupying farms across Eden Valley where place names reveal Danish presence

Carlisle was destroyed in 875 AD. All its inhabitants were killed. The slaughter was so fearsome that nobody wanted to live there for two hundred years afterwards. At least, that’s what is supposed to have happened according to one of the most authoritative medieval chroniclers.

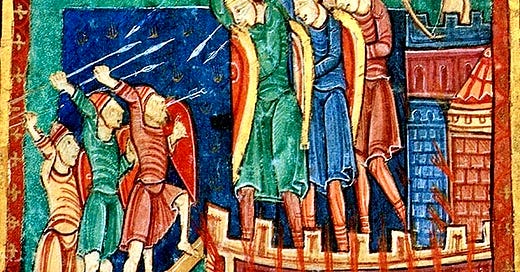

The perpetrators of this horror were said to be the Great Heathen Army of Danish warriors that rampaged across Britain in the late ninth century. One thing is certainly true – a large number of Danish warriors did land in East Anglia in 865 AD. But whether they descended on Cumbria and wreaked havoc has always been a bit mysterious. So, this chapter is a sort of detective story.

It is aimed at finding out what really happened in the north-west in the wake of the Danish invasion during the era of Alfred the Great, and what, if any, legacy it left. The invading Danes were led by a wrathful Viking commander, Halfdan Ragnarsson. He arrived with a highly mobile force of up to 5,000 Scandinavian warriors from bases in the Low Countries.

Their aim was to take revenge against the Anglo-Saxons for the death of Halfdan’s father, Ragnar Lodbrok. Halfdan’s fearsome brothers and half-brothers came along. They were the colourfully named Björn Ironside, Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye, Ubba, Hvitserk and the legendary Ivar the Boneless.

They were all highly experienced warriors. Ivar was held in particularly high regard as a fighter across Scandinavia. He was the glue that kept the otherwise argumentative Great Army unified. Coming together like this was unusual. Scandinavian war bands rarely met except to resolve land disputes, make money, or kill each other.

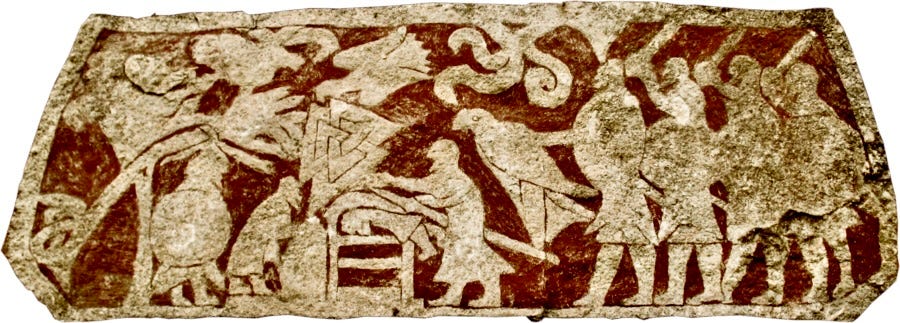

Ivar was an advanced technician of death. He specialised in executing his enemies by the “blood eagle” method - severing a victim’s ribs from his spine and pulling out their lungs through the slits to create a pair of “wings.”

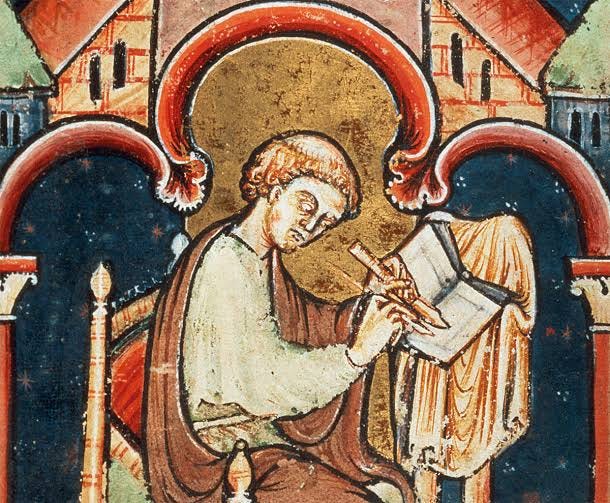

The raid on Carlisle was recorded in the early 12th Century by a monk known as John of Worcester. He mentioned it in an entry about a military campaign in 1092 AD by the Norman King William II who conquered Cumbria and made it part of England for the first time. We know this king as Rufus the Red. He was William the Conqueror’s son.

John wrote: “the king went into Northumbria and restored the city, which is called in the British tongue Cairleu, and in Latin Lugubalia (Carlisle).” The monk added that Rufus “built a castle there; for this city, like some others in that quarter, had been laid in ruins by the heathen Danes two hundred years before, and had been uninhabited up to this time.” Many subsequent historians have been unsure whether to believe in John’s account. This hesitation was no doubt because John compiled his chronicle two centuries after the alleged Danish outrage and there are no accounts by contemporary witnesses to compare it with.

The destruction of Carlisle does get a mention in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. Mike McCarthy’s excellent 2017 history, Carlisle: A Frontier and a Border City also quotes John too, although Mike hedges his bets by declaring: “Whether it was ever attacked by the Danes is an open question” and he adds “we can be sure it was never deserted.”

Yet there is some evidence that that the city continued to be occupied after the raid. It came in the excavation of an elite Viking-age cemetery under Carlisle Cathedral in 1988. Among the grave goods was found a single tell-tale fragment of Torksey pottery. Torksey in Lincolnshire as we shall see later, was the site of a Danish army overwintering camp.

Thanks to recent archaeology and dialect studies there is growing evidence that the raid or, certainly, a major incursion by Danish forces into the place we now know as Cumbria, did take place.

Among the towns and villages colonised by the Danish Great Heathen Army were: Appleby, Brough Sowerby, Rookby, Colby, Kirkby Thore, Temple Sowerby, Ellonby, Sowerby Row, Wiggonby, Newby West, Kirkby Stephen and Oughterby. (For more info, see below)

During this period, a number of Danish words entered the local language while a string of rural settlements, particularly up the Eden Valley leading to the Carlisle plain bear names with Danish components. In fact, the indications are that something strange and much more significant took place than a single bloodthirsty attack on the city.

But to understand what happened we need to grasp the enormous scale of the fourteen years of conflict.

The Great Heathen Army was launched against Britain to take revenge for the killing of Ragnar by Aella, the king of Northumbria. Hundreds of sleek, shallow-bottomed ships capable of sailing across oceans and up rivers landed in East Anglia in 865 AD. It was the largest Danish force ever to cross into Britain. Viking armies had overwintered in Britain before. But this time was different: it quickly became clear they were strong enough to embark on political conquest.

The Army began attacking the four Anglo-Saxon kingdoms that controlled the territory that would eventually become England. By the mid 870s, three of them, East Anglia, Northumbria, and Mercia had fallen to the Danish campaign of plundering, raping and town burning.

Only the southern kingdom of Wessex escaped this fate because Alfred, who was crowned King of Wessex in 871. The Danes were surprised to discover that Alfred had massively strengthened Wessex’s defences. They were forced to concentrate their attacks on less well-protected lands to the east, west and north. The other factor they had not anticipated was the development of Danegeld. The Anglo-Saxon King had raised vast amounts of cash and kept it ready to pay the attackers to go away. Collective Danish resolve was weakened by this because individual war bands were easily tempted to go for the money.

This lack of unity was the Danes’ greatest weakness. At home during the Viking age, Danish tribes had fought each other incessantly over scarce land, food supplies, regional rivalries, and family feuds. Halfdan always known that keeping such a fractious force together would be tricky once the initial goals had been achieved in Britain.

So, despite its early successes, the Great Army was weakened by many flaws at its core. The alliance of Danish tribes was an uneasy union of war bands from small independent Scandinavian kingdoms and communities whose leaders had differing aims. They were poorly prepared, loosely coordinated and they chose targets to attack somewhat on impulse.

Rebuffed by Wessex, they moved on to their real target, Northumbria, arriving in York without warning in late 866, on All Saints Day. After chaotic and brutal street fighting, Aella was captured and, it is believed, suffered the ritual “blood eagle” death. The Danes installed a puppet as king of Northumbria, a man named Ecgberht, and they began collecting taxes on his behalf. Those Northumbrians who declined to pay were killed.

Then the Danes invaded Mercia, captured Nottingham, and made peace. In 870, Ivar the Boneless disappeared from the records, presumed dead. An 11th Century manuscript called the “Fragmentary Annals of Ireland” claims Ivar was felled by a “sudden and horrible disease.” His loss was a terrible blow to the morale, stability, and command structure of the Great Heathen Army.

With Ivar gone, Halfdan became the main Danish commander. He immediately invaded Wessex but Alfred’s well-organised resistance soon forced him to withdraw. In all, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the Danes fought Wessex nine times, including at the battle of Ashdown in 871, but could not beat it. So Halfdan accepted a truce from Alfred.

A remarkable archeological excavation has given us a snapshot of the Great Heathen Army just before it attacked Carlisle.

The force spent the winter of 872-3 camped on an island surrounded by marshes just to the east of the River Trent near Torksey. A remarkable archeological excavation has given us a snapshot of the Great Heathen Army just before it attacked Carlisle. It showed that the Torksey camp comprised up to 5,000 warriors, hundreds of prisoners in chains, craftworkers, merchants, metalworkers, and coin minters with 300 or more flat-bottomed longships, each capable of carrying thirty men. The army had amassed an enormous amount of wealth in the form of gold and silver, both from loot and tribute.

In 873, having been in the country for eight years, the Heathen Army made a fateful decision. It split, no doubt after a blistering row about strategy. Half of the marauding force travelled north under the stewardship of Halfdan. He appears to have accepted money from Alfred to abandon his attempts to conquer Wessex. The other half, under Guthrum, moved south to renew the war against Wessex. Eventually, as Halfdan suspected, Wessex’s king Alfred defeated his army at the Battle of Edington, leading to peace and Guthrum’s agreement to be baptised and to split the kingdom between them.

For his part, Halfdan headed through Northumbria en route to attacking the Kingdom of Strathclyde which stretched from Loch Lomond to the Celtic kingdom of Rheged south of the Solway. This realm was also known as Cumbria and its inhabitants the Cumbrians.

So why did the Danes attack Carlisle? Well, with its Roman fortifications it was an immensely strong military centre controlling access to the north-west of England - and thus it was a severe threat to Danish power in Northumbria.

Register to read the rest of this article. This is an extract from a chapter in a new book called The Trophy at the End of the World. You can buy it instantly here:

: https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/the-trophy-at-the-end-of-the-world

Or you can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick or Carlisle and Sam Read in Grasmere.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.