How the Cumbrian co-op farm pioneer blew his fortune

Early vegetarian William Lawson launched an experimental farm in 1862, sharing profits with his labourers. Scornful neighbours predicted failure - but they were only partly right.

In an era when wealthy Victorian farmers treated restive and unruly agricultural workers with as much tenderness as they would a horse-drawn harrow, William Lawson’s offer was frankly astonishing.

He was a highly unusual member of the Cumbrian gentry. The 26-year-old vegetarian and opponent of blood sports offered to give one-tenth of the annual profits from Blennerhasset Farm near Wigton that he had inherited from his baronet father on February 2, 1862, to his labourers.

But when he invited his workers to vote on whether to accept this free gift and run the farm together as a co-operative, only one put their token on the “co-operation” bottle and ten wary Cumbrians opted for the “every man for himself” container.

Their decision was not quite as mystifying at it seems. Victorian agricultural workers were used to masters trying any ruse they could to buy their labour as cheaply as possible, and “co-operative” sounded like another.

The average farm workers’ wage then was eleven shillings a year, worth £3,848 in 2023, barely a fifth of the rate today. Successive Enclosure Acts had confiscated six million acres of fields previously held in common by poor rural people over the previous century. So English farmworkers were the only peasants in Europe without their own land. Discontent was constantly erupting among the insecure labouring class.

But the gap between rich and poor was the very issue the issue William, the descendant of a family of inveterate liberals, was trying to reduce. Full of philanthropic ardour, in 1866 he went ahead anyway, offering “co-operation to all comers regardless of their opinion.”

From the outset, critics confidently predicted Blennerhasset Model Farm would be an unprofitable folly. From one point of view, they were right. Thanks to multiple disasters the farm made a profit in only two out of the ten years the experiment lasted.

Lawson blamed his own inexperience in buying new-fangled steam ploughs that constantly broke down, acquiring a huge amount of bird-dropping guano fertiliser “worth far less than I paid or it”, choosing unprofitable crops, potato blight and a major fire caused by the manager of the farm’s innovative town gas plant trying to repair a leak using a lighted candle. But complete folly, it was not, as we shall see.

A typical Victorian, Lawson was driven by all the conflicting impulses of the era: idealism, opportunism, muddle and determination. At least 2..5 % of the farm’s revenue funded contributions to the “Public Good” such as a bath house (burned down in the gas fire), a free school, evening classes and innovations such as an artificial manure works, a laboratory, a dispensary and co-operative shops in Blennerhasset, Ireby, Carlisle and Newcastle.

There were successes. 1870 was the year of the “Great Bonus” when the farm made £181 profit, yielding £11 for each worker (worth £700 in 2023.) The biggest failure was “Cyclops”, John Fowler’s twelve horsepower Steam Plough Number 2, the first of its kind in Cumbria. Despite shouts of “she’ll nivver get up Thompson’s Brow” she chuffed her way unaided from Aspatria railway station arriving triumphantly at the Lawsons’ ancestral Brayton Hall only to get hopelessly bogged down in the mud.

The steam engine was supposed to send the plough towards an anchor planted at the other side of the field. Unfortunately, the anchor moved instead, resulting in no ploughing.

In Christmas 1866, William, a committed non meat eater, staged the first of five annual Vegetarian Festivals. A thousand guests were treated to a “fruit, grain and vegetable meal” consisting of raw turnip, boiled cabbage, boiled wheat, boiled barley, shelled peas, oatmeal gruel, boiled horse beans and boiled potatoes.

He also presented a salad made from chopped carrot, turnip, cabbage, parsley and celery, served with a congealed sauce made from boiled linseed. There was no salt and pepper or other condiments, and everything was cold except the potatoes. And because Lawson had insisted the food should have a truly British flavour, the menu excluded rice, raisins, currants, sugar and other readily available imports.

To compensate for the rigours of this poorly prepared and unpalatable repast each guest on rising from the table received an apple and a biscuit.

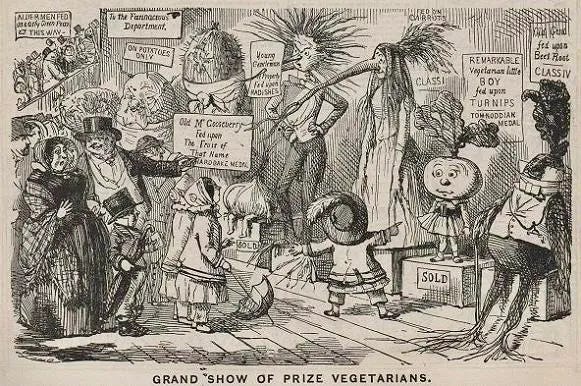

The turnip-crunching celebration captured the imagination of the international media with the raw Yuletide fare being ridiculed in Punch.

Under the headline “A Queer Christmas Day”, the satirical paper’s January 12 edition mocked: “Hunger is said to be the best of sauces; but even that condiment appears to have been as absent from Mr Lawson’s board as salt, vinegar, mustard, and pepper.”

It went on: “Phrenology is enumerated among the entertainments provided for the vegetarians of Blennerhasset. What had it to say to their heads? Perhaps that the development of vegetarians coincided with that of teetotallers, and that both were also equal in quality of brain.”

Today, many people write off the Lawson family’s involvement with co-operative ventures as a farcical waste of money. But the truth is rather different. In 1870, inspired by the year of the Great Bonus at Blennerhasset, Sir Wilfred advised a small group of farmers including William Norman and John Twentyman to form a workers’ cooperative to buy animal feed, seeds, agricultural equipment and manure directly from the manufacturers in order to get lower prices.

This resulted in England's first member-owned farmers’ collective, the Aspatria Agricultural Cooperative Society. In 1976, the society dropped the word co-operative from its title and in 1990 changed its name to Aspatria Farmers Ltd. Today 980 farmers are fully signed up members each paying a £100 annual fee to belong. Its aims remain the same. “This business is run for the benefit of members, and always will be,” the organisation declares on its website. The Blennerhasset Co-operators live on…

—-

I hope you enjoyed this free extract. You might be asking why, if I can read this for nothing, should I sign up for a paid subscriptionJ The answer is: paid subscription readers get exclusive material drawn from my forthcoming books. I offer things that cannot be seen elsewhere and articles that contain the most up-to-date research about the history of our favourite place!

This is a short extract from a new book called Secrets of the Lost Kingdom. It is officially published on September 1 but you can pre-order now. You can buy the book at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, at the Moon & Sixpence cafe in Cockermouth and Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, and Sam Read in Grasmere.

You can also order by post instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/secrets-of-the-lost-kingdom