How historical ignorance wrecks Cumbrian farm livelihoods

Bourgeois myths that sheep eat trees and cherry blossom should flourish on top of Great Gable are pushing Lake District families out of agriculture

After yet another polemical piece appeared in the media claiming sheep eat trees and that they have “denuded” the Lake District of wildlife…here’s a few thoughts.

An Oxford University academic climbed to the top of Great Gable. She noticed the lack of trees and shrubs on the rocky summit and issued an angry post on the social media site X, formerly known as Twitter.

It read: “The sheep have eaten everything.”

The author was Dr Emma Garnett, a Green Party campaigner whose professional work involves researching ways of reducing the impact of food transport on the environment. She complained there was no “blossom” on top of the mountain, declaring: “We hiked for 8h on a sunny April day - I don't think I saw a single flower or insect on the peaks.”

A large proportion of the British public will give a big cheer on hearing Emma’s remarks. Two out of three of us thinks the Government is not doing enough to protect the environment, according to pollsters YouGov. Some 57% think natural habitats are getting worse.

But the problem is Emma’s statements are wrong. They are based on a lack of awareness of Cumbria’s climate and its history. Yet such claims are contributing to a growing cross-party consensus that the Lakes must be returned to a “wild” state that never existed except in the imaginations of 19th Century Romantic poets.

This longing for the unattainable means that indigenous Cumbrian farmers are currently being penalised because the real Lake District falls short of the “wild” ideal that only ever existed in the heads of comfortable urbanites. Farming families across Cumbria are facing massive subsidy cuts combined with impossible Government demands to return the fells to their supposedly “original” uncultivated condition with the help of either Government action or market mechanisms.

Families who have farmed the Cumbrian soil for generations and who made the remarkable landscape that was awarded World Heritage Site status in 2017, are being pushed into bankruptcy and ultimately off the land. This is a remarkably poor reward since hill farmers do far more than produce wool and meat. They create and maintain world famous beauty.

Before we look at the real history of Cumbria, let’s deal with Emma’s complaints. After she went up into the mountains on April 22, she published a picture of the panorama and wrote: “Look at this view of Great and Green Gable. You cannot see a single tree or shrub.”

Emma added: “There are National Trust donation boxes asking us to help conserve the Lake District - your emblem is literally an oak leaf - why would we want to conserve these unnatural, treeless landscapes?”

The first thing to say is the summit of Great Gable is 2,949 feet high and the summit has a climate appropriate only for rare Arctic plants such as the alpine cinquefoil which does not bloom until the summer begins on June 20th. The top is also 1,194 feet above the tree line.

No trees can grow above the tree line because there isn’t the correct air pressure, heat, or water to keep them alive.

We put these points to Emma and she chose not to respond. But she might have replied that there are few trees below that line and the sheep must have eaten those. The allegation that sheep eat trees is one of the greatest falsehoods of the modern ecological debate in Britain.

Sheep are extremely efficient grass-mowers. They will graze and browse on many different types of wild plants, flowers, weeds, leaves, tree bark and shoots. But sheep do not kill mature trees. Trees are very hard to kill. A book has just appeared claiming sheep have eaten Britain’s temperate rainforests which are mainly composed of oak. They haven’t. Oaks are poisonous to sheep.

Emma complains of the landscape in another post: “It's desolate, it's depressing, it's barren”. Wrong again. The Lake District has the greatest diversity of ecological habitats of any English upland according to James Drewitt and Hannah Manley, engineering and physics researchers from Bristol University who analysed the place in 1997. Cumbrian farms are renowned for their hay meadows, varieties of wet grasslands, springs and flushes, mosaics of blanket bog, all types of grassland and dwarf shrub heath, they noted.

The real history of the Lake District tells a very different story to the one Emma thinks she sees. Pollen analyses show the region’s forests were cut down by Bronze Age people, 5,300 years ago, using axes to create pasture and fields for cereals.

The first Cumbrians began harvesting food and cutting down trees in this area 10,000 years ago immediately after the last ice age. Farming began 6,000 years ago. The fifty stone circles in Cumbria were built by prehistoric farmers as religious sites and places for trading polished Langdale stone axes. Many of the spectacular scree slopes and caverns admired by walkers are in fact gigantic spoil heaps and access tunnels left over from ancient quarries. There has never been a time when it was an uncultivated and unexploited wilderness untouched by human beings. Aside from being an important agricultural area, the Lake District and Cumbria is thickly festooned with abandoned industrial sites that produced coal, iron, copper, lead, stone, cloth, ships, bobbins and gunpowder.

Emma published a picture of a cherry tree to illustrate the flowering she expected to see on top of Great Gable: “Here's a photo from the car driving home from the Lake District: trees, shrubs, blossom!” She added that she saw more flowers beside motorways than in the National Parks: “This is such a crying and unnecessary shame.”

Actually, the Royal Horticultural Society points out that cherry trees are killed by frost. The temperature drops to minus 21 C in winter on the summit of Great Gable, the same as Helsinki in January where the Baltic Sea coast freezes for seven months. For every 1,000 feet (305 metres) in altitude you climb, the temperature drops 2 degrees Celsius. The higher you go, the more spring is delayed.

The Lake District mountains are a much harsher environment than a sunny day in April might suggest, which is why there were 2,154 emergency callouts to mountain rescue in the Lake District between January 2019 and July 2023.

A huge proportion of those people suffered hypothermia while there were 25 deaths in 2020. The ecology of the Lake District reflects the extreme conditions.

As the RHS said: “Cold weather may contribute to premature initiation of flowering.”

Emma’s protests further extend a worrying trend in which people who care about the environment feel morally justified in publishing whatever acerbic criticisms they feel like making - irrespective of whether they have any basis in truth.

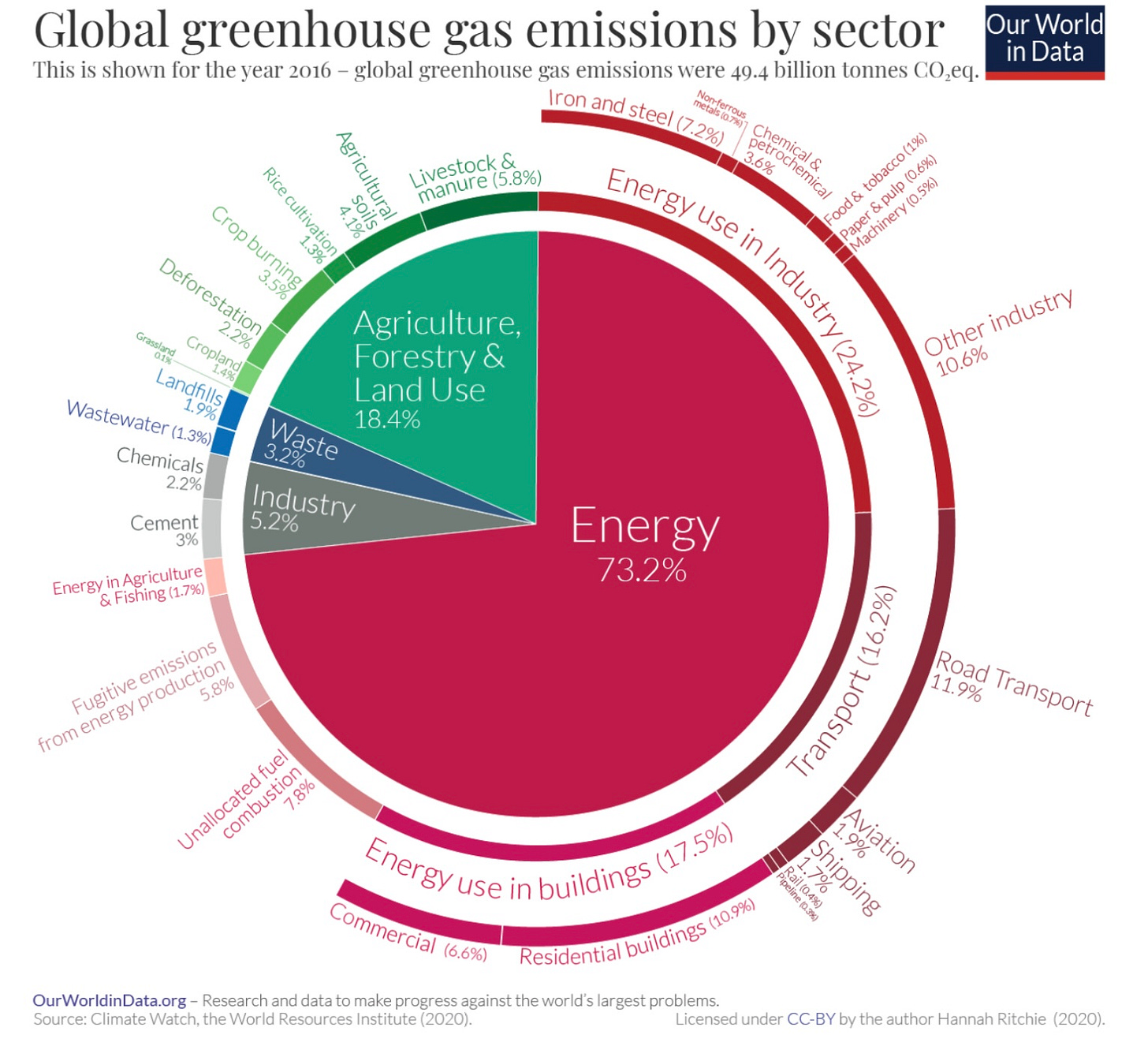

There is a great myth among vegan campaigners especially that agriculture is the major creator of greenhouse gases. In fact this is completely untrue as this graphic below shows. Energy use by industry and families is vastly more damaging and far less justifiable than food production.

Minsters have exploited this climate of growing hostility to farmers.

During the 2016 referendum, Premier Boris Johnson told farmers’ meetings, such as one at Gisburn Auction in Lancashire, that “subsidies will stay, 100% guaranteed.”

Under the old EU subsidy scheme, worth £3 billion a year, about 90% went to farmers in Basic Farm Payments. This paid farmers £100 per acre to look after the land. After Boris’s reassurance, 58 percent of farmers voted for Brexit.

Unfortunately, Boris’s guarantee was worthless. In 2020, the Johnson government announced a complete phaseout of Basic Farm Payments by 2027. Boris told Commons that, instead, the money would be diverted to returning the Lake District to an uncultivated state: “What we are going to do is use the new freedoms we have after leaving the CAP to support farmers to beautify the landscape”.

That sounded reasonable. But instead, Cumbria’s farmers have been plunged into a bewildering thicket of green incentives called Environmental Land Management schemes. In theory, they are eligible to get money according to how many out of 280 different “actions” they take to preserve the environment. But to get it they have to compete for cash to, for example, plant new woodland or create a nature reserve. Only one in eight farmers have thought it worthwhile to apply.

The Lake District National Park Authority is working with farmers on ELM schemes to create more nature friendly ways of farming, flood management measures, rights of way for public access, ancient woodlands, native breeds of livestock, plants, soils including peat, to cultural heritage and the historic environment. Lovely though that sounds, the actual outcome is that Cumbrian farmers suffered an average 22% cut in subsidy in 2023 and in 2024 payments will be 36% lower.

With farmers already paying sky-high prices for fertiliser, fuel, energy and feed, it is not surprising that farming families are quitting the land in unprecedented numbers. The number of farm holdings fell by 30,000 in 2005 to 104,200 in 2015, according to the Campaign to Protect Rural England. In other words, eight farmers quit every day.

This is an extract from a forthcoming book. You can read more like it in my latest, The Trophy at the End of the World. You can buy it instantly here:

https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/the-trophy-at-the-end-of-the-world

Or you can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick or Carlisle and Sam Read in Grasmere.