How Edward II’s love life let Robert the Bruce ravage Cumbria

The "worst king in history" was handed the crown in Carlisle after his warrior father died at Burgh-by-Sands. His devotion to corrupt favourites led to famine, death and destruction across the North

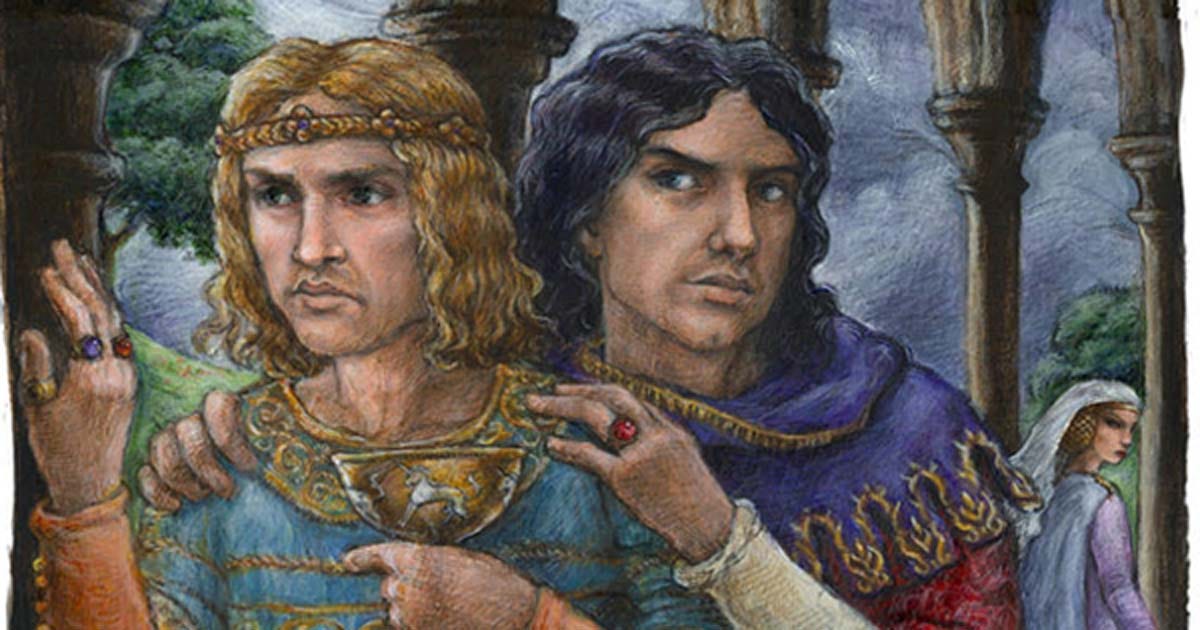

On Wednesday, 20 July 1307, a strong and handsome young prince with long, fair, wavy hair entered the Great Hall of Carlisle castle’s massive sandstone keep. Standing over six feet tall, Edward of Caernarfon looked healthy, athletic, and regal. He was ushered towards a temporary throne in a ceremony hastily convened to proclaim him King Edward II of England.

But as he sat down in solitary splendour his attempt to project effortless superiority was marred by the weak little face that peeped from behind his bushy beard.

The raising of the 23-year-old boy to supreme power took place thirteen days after the agonising death by dysentery of his father, the military colossus Edward I, one of the most influential kings of the medieval period, at nearby Burgh-by-Sands. The elder Edward was a formidable act to follow. He had vastly reduced the influence of the English barons and conquered Wales.

Edward I had fought relentlessly to do the same to Scotland, earning himself the nickname the Hammer of the Scots. In keeping with his long career as a war-hungry and successful warrior-king, the elder Edward drew his last breath surrounded by his army while encamped on marshland overlooking the Solway Firth within view of Scotland.

He was on his way to a clash with Robert the Bruce, probably the central character in the history of Scotland. Edward was furious that his frivolous son was partying with his cronies in London, rather than fighting by his side. By way of an apology for his absence, the youth had sent his father a barrel of sturgeon.

The ordinary people of the realm, who for thirty-five years had endured a reign of terror under his ferocious and unpredictable father, rejoiced. They hoped the accession of the pretty, likeable, and boisterously good-humoured prince would bring a period of peace.

But the serious men of the court, the cream of England’s nobility, who queued up, dropped to one knee, kissed the young man’s nervous hand, and swore oaths of fidelity, shuddered silently with horror. They had long dreaded the day when the youth they regarded as eccentric, idle and vicious would become master of their fates.

They were right to tremble. Whether Edward the younger realised it or not, his father had left him an unwinnable war, an empty treasury and a council of advisers full of senior lords enraged by the elder man’s incessant demands to provide soldiers. The expensively and often bizarrely dressed Edward junior rarely rose from his bed before noon. He delighted in leading his pet lion, which cost 4d a day (£10 in 2023) to feed, around the Tower of London on a chain and playing the kettledrums in his ample spare time.

With offbeat habits such as these, England’s power brokers shuddered that this hedonistic young man lacked the skills to carry on a war against the ambitious, decisive, and charismatic Bruce who possessed a breath-taking military genius.

The ravaging of the north by Robert the Bruce, which was particularly intense between 1311 and 1322, has left a deep but rather vague folk memory behind in Cumbria. But this historical period decisively shaped the region we know today. So, it is worth going into detail to reveal the story of one English king’s outlandishness, stubbornness, and incompetence.

Most historians rate Edward II as the worst king in English history. During his lifetime, not everyone thought him a bad man. He was loyal to his friends, generous and kind to people he loved and who pleased him. He could be amiable and good natured; he threw good parties, was an engaging conversationalist and a pious Christian. But he was also vain, indecisive, foolish, and wildly emotional.

But his principal shortcoming was that he failed to protect his people. Apart from his catastrophic loss of Scotland to Robert Bruce at the battle of Bannockburn his key deficiency was that after 1314, he allowed the northern counties to be savagely pillaged and burnt by the Scots.

The story of Edward II’s reign is a perfect illustration of how the north is especially vulnerable when a delinquent who cares more for his personal interests than those of his people gains the levers of power. The Scottish raids left psychological and visible wounds. The northern English frequently express a mix of resentment and envy towards Scotland. Cumbria’s five hundred fortified houses, scores of peel towers and hundreds of farms huddled together in defensible villages across the northern landscape are a concrete reminder of that friction.

For the past four hundred years it has been popularly believed that Edward was toppled because the most powerful English barons disliked his homosexual relationship with his favourite, a relatively low-born French noble called Piers Gaveston. But Edward’s failure had more to do with his military incompetence and insensitivity to the way power worked in the English court than his carnal preferences.

The real trouble was, Edward needed to have a male favourite by his side as a trusted counsellor and proxy in order to function. This disrupted the traditional hierarchy of power in the court. The attempt to rule through a surrogate was a major issue because in medieval culture, rank and status dominated everything, down to what kind of material people wore, where they sat and what they ate.

Gradually, Edward the younger consciously recoiled from the burden of expectation his father placed on his shoulders, spending more time with undemanding chums and as little time as possible in his father’s presence. The problem wasn’t stupidity. Edward owned a small collection of books and was no intellectual, but his frequent characterisation as an illiterate dunce is unfair. Above all, his decision to install men like Gaveston, and later Hugh Despenser, as his human shields over the heads of powerful lords sealed his eventual doom. Gaveston was a famously courageous and chivalrous knight. He was charming, witty, and self-confident. But, feeling secure in Edward’s unshakeable favour, he could also be sharp-tongued, irreverent, and arrogant.

Edward’s worst mistake was to waste time pleasure-seeking in London and cavorting with his mates at his favourite palace, King’s Langley in Hertfordshire, drinking to excess, playing music, racing horses, and feeding his pet camel. He ought to have been focused instead on the doubtful security of England’s northern border.

Once Edward I was dead, the younger Edward’s lack of seriousness and neglect of duty gave Robert the Bruce a three-year break during which there were no attacks by English armies. This failure to engage was a serious blunder by Edward. The Scottish king used the respite to secure his fragile grip on power.

Robert the Bruce toured Scotland killing and repressing his enemies. The speed of this ruthless purge left Robert’s rivals no time to band together. Now unchallengeable, Robert was free to concentrate on confounding the English. By allowing the Bruce time to strengthen his base, Edward paved the way for England’s greatest military defeat at Bannockburn, a rout so complete Robert was free to launch devastating raids across Cumbria and the north for the rest of Edward’s reign.

Edward seized the chance to secure concessions that went some way towards promoting England’s overlordship over the Scots. Finally, Edward provoked war by refusing to concede that Robert the Bruce was an independent king and he set about hunting down and destroying Robert with all the cruelty and brutality he was capable of. But his quest fizzled out when, aged 68 and stricken by an intestinal infection, he was camped with his men at Burgh-by-Sands on 7th July 1307 within sight of Scotland over the Solway Firth.

The King’s messengers galloped the 315 miles to London in a mere four days in order to tell Edward this father’s death. They found the younger man on 11th July 1307 ensconced in the comfort and safety of Lambeth Palace on the south bank of the Thames. Just as his father had feared, the new monarch’s first thought was not about how to meet the growing Scottish threat to the north, but something much nearer to his heart. In his first official act as king, he recalled Galveston from exile where he had been sent just ten weeks before by Edward I as a punishment for deserting the army and attending tournaments instead.

Contemporary chroniclers expressed dismay at this strange sense of priorities. The author of the Vita Edwardi Secundi (Life of Edward II) wrote that the new king’s love for Gaveston was “beyond measure and reason… our king was …incapable of moderate favour.”

With his tyrannical parent out of the way, the new king headed north. He arrived at Burgh-by-Sands on 19 July to view his father’s body. After his joyless proclamation as king in Carlisle castle the following day, Edward travelled thirty miles to Dumfries. There he received the homages of those Scottish lords who were still loyal to England. He ventured timidly into Galloway and took comfort from the fact the Bruce was offering no obvious resistance. He was not inclined to pursue the fugitive up hill and down dale. Edward told himself that continuing the war was unaffordable anyway.

So, in clear dereliction of his duty and in defiance of all common sense, the new king returned to Westminster at the end of August. He attended his coronation and completed the delicate negotiations required for his marriage to the eleven-year-old Isabella, daughter of Philip IV, King of France.

Even before Edward crossed the border heading south, he was joined by the flamboyant Gaveston. He promptly raised his significant other to the peerage as the earl of Cornwall. Edward’s courtiers were scandalised. They could not believe that a title originally reserved for one of the king’s young half-brothers had been bestowed on the low-born foreigner. Jealous nobles rebelled in protest at the elevation of the smirking and supercilious Gaveston.

The Vita Secundi makes it clear that aristocratic unrest erupted from the outset of Edward II’s reign. “The seditious quarrel between the lord king and the barons spread far and wide through England, and the whole land was much desolated by such a tumult … it was held for certain that the quarrel once begun could not be settled without great destruction,” the biographer wrote.

Knowing Edward II was embroiled in a political crisis, the Bruce came out of hiding. The Scots king marched his forces into Galloway, laying waste to land, houses, villages, towns, and great estates. Hundreds of pro-English refugees poured over the border into Cumbria and the forest of Inglewood between Carlisle and Penrith. Those who bravely remained behind were forced to pay hefty fines on pain of death. Robert assigned his most feared knight, the indomitable James “The Black” Douglas, and a small contingent of men to continue extending Scottish royal authority into England by force.

By the beginning of 1309 it was clear to Edward that the Bruce intended to keep butchering, decapitating, and devastating his way southward. He reluctantly acknowledged the Scotsman would not relent until he achieved full recognition of his status as the independent king of Scotland. But the English barons, still furious at Edward’s behaviour, refused to organise or pay for a military response. Edward was therefore forced humiliatingly to sue for a temporary truce with his Scottish adversary until the autumn, although he still refused to acknowledge Robert I as king of Scots.

When the ceasefire period expired, baronial resentment over Gaveston was still seething. So, in November, Edward instructed the commanders of his garrisons at Berwick and Carlisle to hold talks with the Scots to bargain for further separate truces lasting until the middle of January. Robert obliged.

Edward’s Scottish allies warned this act of appeasement was a mistake. If he did not smash the growing power of the Scots soon, they warned, the crucial castles England held north of the border would be lost “by default and laxity.” The dangerous accusation that he had “lost Scotland” forced Edward’s hand.

Through his own ineptness, he had left himself with no choice but to march north with inadequate forces. Inevitably, the move was a fiasco. The English king spent almost a year there but failed even to engage Robert Bruce in battle once, let alone defeat him. Edward finally bowed to the inevitable, returned to London at the end of July 1311 and summoned Parliament where he expected to be berated by the great and powerful for his incompetence.

Of course, once Edward was safely tied up in London dealing with the political mess that he had created through his own stupidity, Robert reappeared and began his notorious campaign of raids terrorising the north of England, burning, pillaging, and taking prisoners for ransom. Whitehall records show the Scottish army seized a huge amount of property, livestock, and treasure. Typically, the price of arable land burned by the Scots halved in value from 6d to 3d an acre.

The people were so impoverished by the raids that Edward was forced to exempt Cumberland from all six rounds of Government taxes levied between 1313 and 1327. England’s barons were exasperated by Edward’s military incompetence. In February 1310 they called for a twenty-one strong committee of nobles and senior churchmen known as the Lords Ordainers. This body set about punishing the king for his failings.

The committee issued forty-one Ordinances drastically curbing the king’s powers. The Ordainers gave themselves a veto over all future royal appointments including the important local sheriffs and they removed Edward’s power to declare war.

The regulation that caused Edward the most pain was the twentieth which read: “Piers Gaveston, as a public enemy of the king and of the kingdom, shall be utterly cast out and exiled … forever and without return.” Edward tried shouting insults to change their minds. When that failed, he switched to flattery. Neither approach worked.

The barons warned Edward that if he refused to accept Gaveston’s banishment he would be “deprived of his throne and his kingdom.” Edward's subjects split into two groups: those for and those against their ineffectual king. Only four years since his accession, therefore, Edward had driven his kingdom to the verge of civil war. The growing devastation of the North would threaten his very survival as king.

This is an extract from a chapter in a new book called The Trophy at the End of the World. You can buy it instantly here:

: https://www.fletcherchristianbooks.com/product/the-trophy-at-the-end-of-the-world

Or you can pick up a copy from the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, Bookends in Keswick or Carlisle and Sam Read in Grasmere.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.