How Cumbrian lake inspired mourning Tennyson to tell King Arthur’s tragic story

The depressed, hard up poet pawned his Cambridge prize for a ticket to a Lake District holiday with friends...and wrote a masterpiece

If you climb a hill near Cockermouth and look east you can see the shining levels of Basssenthwaite Lake shimmering six miles away.

Peer a little further down its far shore and you may just be able to spot a remarkable stately home called Mirehouse.

Built in the year of the Great Fire of London, 1666, the place has inspired so many famous writers that broadcaster Melvyn Bragg dubbed it the “Manor from Heaven.” Mirehouse with its splendid library, manuscripts, antiques and portraits is one of the most staggeringly well-positioned houses in the Lake District.

Tucked under the cone-shaped mountain called Dodd it is blessed with gardens surrounded by walls built of mellow brick that keep the flowers several degrees warmer than the surrounding air. The house has woods with rare Scotch Pines, larch and oak.

You can walk across its fine parkland to the romantically isolated 1,000-year-old Celtic church named after St Bega, reputedly a 7th century Irish princess who fled her native land to avoid an unwelcome marriage. More likely, the name refers even further back to a pre-Roman Celtic goddess called Brigantia. The tiny church nestles beneath an eye-popping backdrop - the vast silver lake and the green immensity of Sale Fell on the opposite shore.

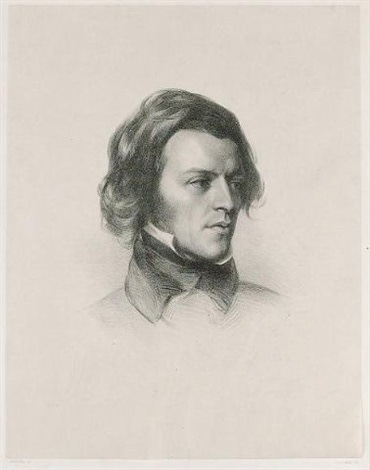

In the spring of 1835 an emotionally exhausted and hard-up 24-year-old poet, Alfred Tennyson, pawned his most treasured possession, the prestigious Chancellor’s Gold Medal for English Verse that he had won at Cambridge University. He used the £15 the pawnbroker gave him to pay his fare to Keswick.

He was heading for a holiday at the lakeside house owned by the family of his close university pal James Spedding. Tennyson badly needed to see Spedding. He had been discouraged by the reviews of his second volume of poems that came out two years before that were so wounding he would not publish anything else for 10 years.

But he had also begun his lifelong struggle with debilitating depression following the death of his brilliant friend Arthur Hallam who was cut down by stroke at the age of only 22 while hiking in the Alps. Hallam and Tennyson had formed a deep and close relationship that may have been homosexual.

Spedding’s calm, modest and self-effacing temperament made him a trusted counsellor for Tennyson who was an idealistic, neurotic pessimist. Spedding read many of Tennyson’s poems in manuscript and even wrote positive reviews anonymously in literary journals to help his friend’s sales along.

At Mirehouse, Tennyson met Spedding’s other guest, Edward FitzGerald, who twenty-five years later became world famous for his enormously influential translation of the poem, “Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.” The three young men enjoyed a three-week holiday in this magical spot.

These brilliant and serious men believed they were living in a time of moral, religious and political crisis and schism. The extension of the voting franchise in the Great Reform Act of 1832 had hardly quelled the middle class fear that Revolution was in the air. Science was undermining conventional Christian interpretations of the earth’s history.

Charles Lyell’s recently published “Principles of Geology” had dismissed the orthodox view that the world was 6,000 years old and proposed a timescale of millions of years including several great floods. Lyell argued it was not even scientifically necessary that a God should exist. Tennyson and FitzGerald then departed for a boating adventure where the poet pulled out a notebook.

Fitzgerald wrote: “Resting on our oars one calm day on Windermere, whither we had gone for a week from our dear Spedding’s Mirehouse at the end of May 1835…and looking into the lake quite unruffled and clear he quoted from the lines he had lately read us from the manuscript of “Morte d’Arthur” about the lonely Lady of the Lake and Excalibur:

“’Nine days she wrought it, sitting all alone

Upon the hidden bases of the Hills.’

“Not bad that, Fitz, is it?” said Tennyson.”

It was a pivotal moment for literature. At the time of this greatest personal and, in his mind, national moral and religious crisis, Tennyson had turned to the potent story of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table for inspiration. Tennyson had in fact swiped what was originally a Welsh myth and made it English - and thereby fashioned a tool that would be used to educate and motivate the servants of the British Empire.

He called the poem “The Morte d’Arthur” and it was to become the last of twelve linked poems eventually published as the “Idylls of the King,” that retold the full but then little-known story Arthur, Guinevere, Lancelot, Merlin, and the Knights. Yet the apparently surreal Medievalist landscape of Morte d’Arthur is not an abstract fantasy. It is inspired by and built out of Mirehouse, St Bega’s and Bassenthwaite.

—-

This is a short extract from a fascinating chapter in Secrets of the Crooked River a book about Cumbria, the North Lakes and the town of Cockermouth.

It is on sale at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth.

You can also pick up a copy at Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Also on sale now is our latest book, Secrets if the Lost Kingdom, a book that reveals Cumbria existed for 500 years, effectively, as an independent country.

Buy both books online here: www.fletcherchristianbooks.com