How Coleridge’s tragic daughter sacrificed herself to save her father’s reputation

Samuel Taylor’s brainy Cumbrian daughter gave up her chance of literary immortality to clear her father of plagiarism

In September 1940, when Britain seemed to be facing obliteration in an imminent Nazi invasion, the great novelist Virginia Woolf wrote about a brilliant Cumbrian woman who lived her life only to a fragment of its potential.

Like the children of other great men, the delicate, large-eyed and startlingly beautiful Sara Coleridge was a “chequered, dappled figure”, Woolf wrote. Sara had lived most of her forty-eight years of life in Keswick “in the light of the sunset” of her father Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s intimidating, controversial and complex reputation.

Sara Coleridge would not have ranked herself among the literary stars of Victorian England. She rarely published in her own name and she was shy about publicising her writing even though it showed great intelligence and versatility. Like STC, her greatest skill was talking. She mastered six languages by the age of twenty-two and published two books that gave ample evidence of her genius.

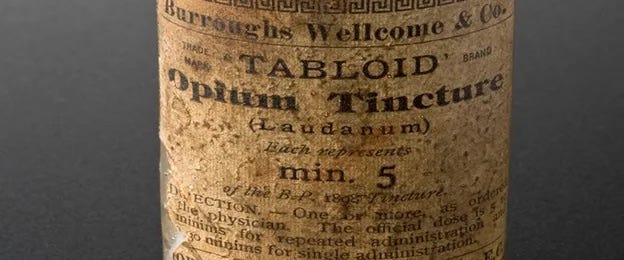

But circumstances conspired to stifle her talent. The early death of her beloved husband, Henry, and the unrelenting demands of parenthood, gynaecological illnesses and addiction to the ubiquitous household painkiller opium, “the aspirin of the nineteenth century”, all served to sap her intellectual energies.

This meant that, like her father’s strange Gothic ballad “Christabel,” Sara Coleridge became for Woolf an “unfinished masterpiece.” Yet her achievements were considerable.

She was an accomplished translator, she wrote highly popular children’s verse including a lovely poem called the “The Months” (the one that starts: ‘January brings the snow, Makes our feet and fingers glow.’) that still appears in children’s anthologies, and the magical prose poem “Phantasmion” that foreshadowed the fantastic world-building of Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

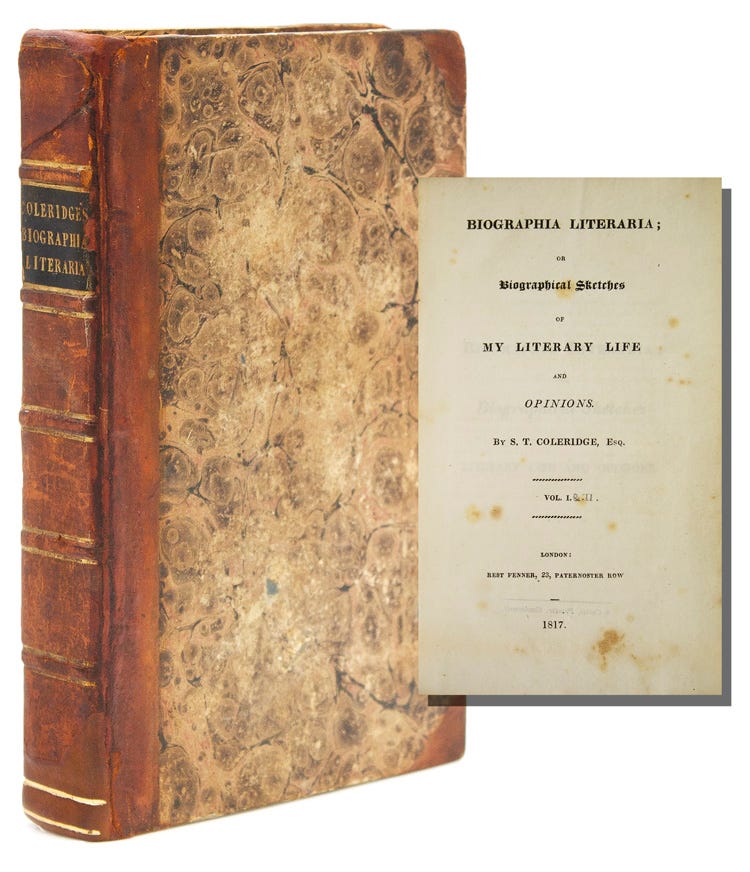

Although she secretly wished she could write for the public with a bold and authoritative voice, she set herself to the thankless but necessary task of editing her father’s scattered and disorganised works, partly to defend his masterwork, the Biographia Literararia, against dangerous charges of plagiarism.

As the biographer Alan Vardy put it: “Sara’s sophisticated scholarly editing” set the benchmark “that has been the hallmark of Coleridge studies ever since.”

Yet like other clever bourgeois women she was trapped in the confines of Victorian society, barred from gaining an education at one of the universities and from making a mark in the professions.

Frustration drove Sara at her most desperate moments to something like hysteria. She received one of the finest early educations possible from her uncle, the Poet Laureate Robert Southey. But former revolutionaries frequently turn into the worst reactionaries and he became a fierce misogynist who believed unmarried women were fitted only to be needlewomen or governesses.

Then, after a short lifetime of struggle, Sara realised she was dying. She was diagnosed with breast cancer but was callously refused medical treatment. This was torture to a perfectionist who could not bear to leave small things incomplete, let alone her whole life.

She lamented not having finished putting her father’s fragmentary works in order and she bitterly regretted not having written her own. These cruel circumstances left her feeling barren and useless.

Her devotion to her illustrious father’s legacy was not self-effacement. She got to know the parent she had hardly met in real life far better than many people. By training her piercing intelligence and literary genius onto giving his brilliant but disorganised work a sense of order she succeeded at the highest intellectual level.

Typically, Samuel Taylor Coleridge was absent on December 23, 1802 when his first and only daughter was born. He had already begun his lifelong, unrequited obsession with a woman who was not his wife: Sara Hutchinson. She lived at Sockburn in North Yorkshire, 80 miles away from his nominal home at Greta Hall in Keswick.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.