How an unknown Roman city rose from the Cumbrian mud in a single night

Devastating 2009 floods removed a mile of soil a metre deep, revealing the largest imperial conurbation in the far north-west of Britannia

The devastating floods brought good news to nobody in Cumbria except, perhaps, its hardy band of metal detectorists.

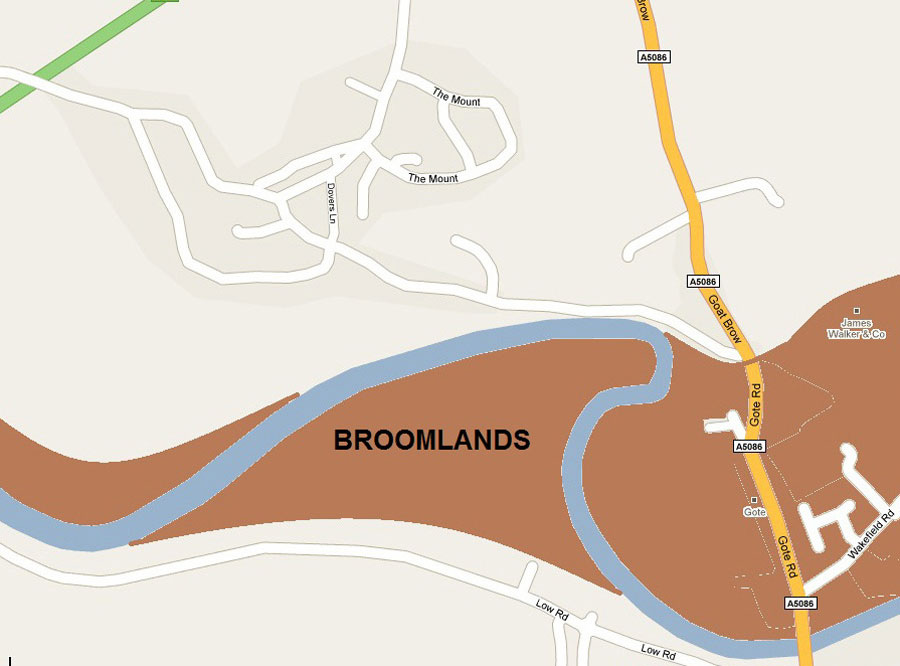

On the terrible night of 19th November 2009, three months’ rain fell in just twenty-four hours in the hills. The River Derwent burst its banks, submerging the Main Street of Cockermouth in up to eight feet of water, causing havoc and misery for the residents. In its hurry to get to the sea, the river ignored its usual looping course and cut straight across Broomlands behind the Lakes Homecentre store.

As the water surged past Papcastle, the site of the ancient Roman fort of Derventio built in 80 AD, it eroded away a layer of topsoil up to a metre deep, uncovering pieces of pottery and other artefacts that had lain buried for almost 2,000 years.

Although nobody knew it yet, the water had exposed evidence of what was probably the largest Roman town in the far north-west of England. For more than 200 years it was larger and more important than the invaders’ military command centre at Carlisle.

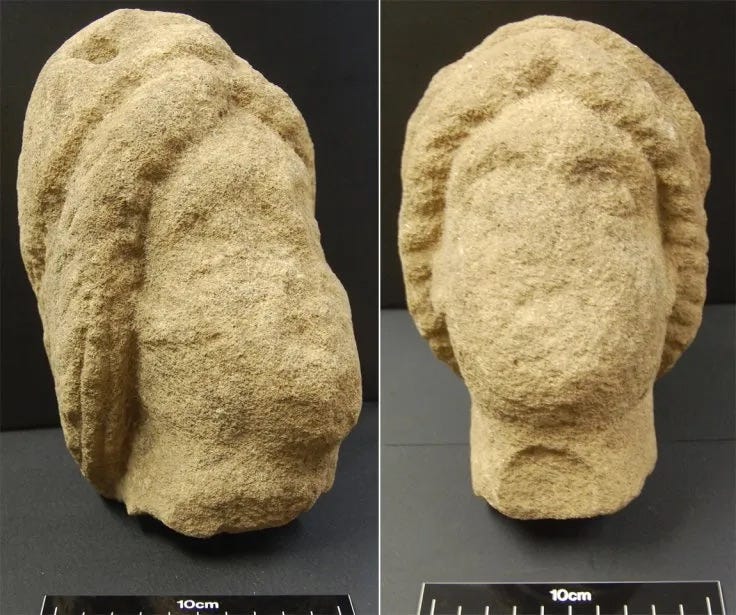

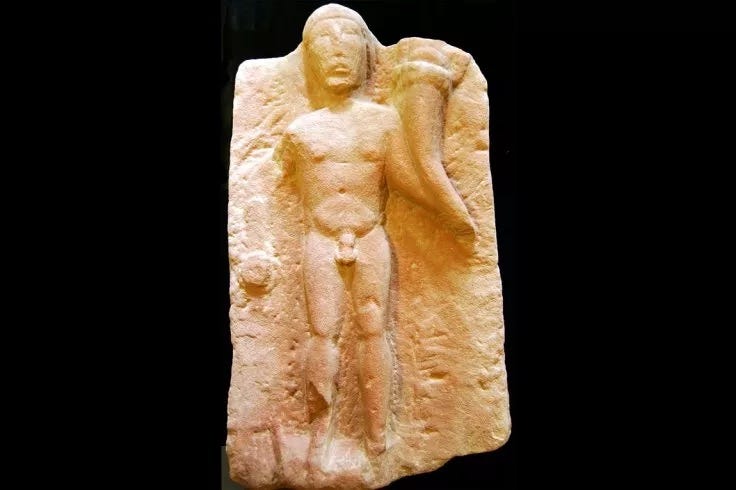

As better weather arrived in the New Year a scattering of treasure hunters started pottering around the fields beside Low Road. Suddenly they began reporting unusually rich finds of coins, pieces of statuary and household items on the south bank of the Derwent where archaeologists had not previously suspected any Roman activity.

Experts knew a civilian town or “vicus” had grown up on the north bank next to the fort. But the new finds showed this town had spread to the other side of the river and the whole thing was vastly larger and much more important than they had thought.

They needed to explore this area urgently. Fortunately, an EU-funded archaeological and cultural organisation called Grampus Heritage and Training Ltd was working on some landscape improvements nearby.

Grampus extended its area of operations to cover Papcastle. They launched a geophysical survey, a sort of x-ray system that uses electromagnetic sensors, to create pictures of whatever lies several feet below ground.

Grampus ran its equipment over Broomlands and then crossed the river to do the same on Sibby Brows field below Papcastle. The images that emerged stunned researchers. The ghostly pictures of the southern side revealed a web of densely packed buildings.

With excitement mounting, the team hired a specialist-contracting consultancy called North Pennines Archaeology to do a four- week evaluation to see whether it would be worth launching a full-scale excavation.

In driving rain the consultants, aided by a crowd of enthusiastic volunteers and excavating machines, dug eight large muddy trenches. It was hard going because over the centuries the river had constantly changed course, scrambling the outline of the archaeological remains and dumping hundreds of tons of sand and gravel on top of them.

They also confirmed the route of a suspected Roman Road. But the most surprising discovery was a whole series of postholes, gullies and hearths. It meant there had once been a much bigger civilian town than experts had thought, on a par with Roman Carlisle, with densely packed timber houses and industrial workshops.

They found a large circular feature about 150 feet in diameter which they thought might be an amphitheatre or horse training ground, the foundations of a bridge abutment, and of a bridge pier linking the two sides of the vicus.

After three weeks of hard graft the archaeologists assembled evidence of a spectacular and extremely rare feature - wooden planks from a Roman millrace and the massive blocks of the first few courses of a mill building. The remarkable find dates from sometime after 200 AD, about 160 years after the Emperor Claudius conquered Britain. It was a hugely important discovery.

Because it illustrates the serious industry the Romans created to keep the army of occupation fed and healthy. This is only the second time in Britain that a Roman mill with the actual water channel that drove its grinding wheel has been found. It is also the most complete example to be unearthed on UK soil.

Up to now archaeologists have tended to find Roman stones used for grinding the grain, but no evidence of actual mills. The digging team also found some fragments of pottery, a few coins, part of a millstone, an incomplete inscription and part of a wall.

Diggers came across a chilling discovery, a skeleton deliberately hidden under the floor of the bathhouse. The bones were wedged into one of the cavities that circulated hot air from a furnace through tubes or passageways called ducts. Only three quarters of the male skeleton remained. It was aged between 24 and 44 years of age. A triangular hole in his skull suggested foul play.

Strontium tooth analysis suggested the victim was a local who died between 170 and 250 AD. They also found an exceptionally well-preserved candelabrum almost six feet tall but were puzzled not to find an obvious water supply, or any loos.

The excavation was overwhelmed by bad weather and the mud was so deep the diggers felt like First World War soldiers. By the time this first formal dig ended it had generated great excitement in the village with up to forty volunteers pitching in.

Overall, the excavation revealed the Romans had occupied the site for more than 200 years, from the 1st to the 3rd century.

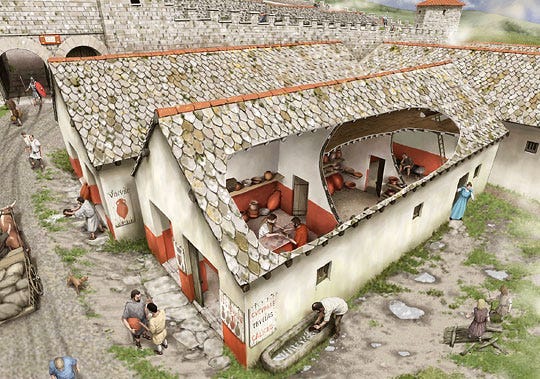

Derventio had begun modestly as a camp built out of wood with simple drainage ditches and pits. As the military importance of the site grew the Roman military put up two big buildings. One was a mansio - a sort of Roman Premier Inn. This was an official stopping place on a Roman road maintained by the central government for the use of officials whilst travelling. In later years the mansio and bathhouse buildings were lavishly upgraded.

After their startling discoveries on the south bank, archaeologists decided to check the north side. There, unlike the ephemeral wooden structures typical of the almost shanty-town quality of the south bank settlement, they found large stone built military-style building around fifty yards square and very clear traces of a metal-working factory.

Armed with their findings, archaeologists threw in a bid for National Lottery funds to carry on a further three-year dig and were successful.

The next major excavation ran from August to October 2012. With the support of eighteen volunteers the team immediately found a substantial main building and a small bathhouse featuring the distinctive curving wall of a laconicum (warm dry room). Apart from the outstanding and rare remains of a corn mill and the skeleton in the bathhouse there was a curved building they believe might have been a horse-training centre.

Overall, Derventio fell into clear historical phases. The fort reached its high point with the construction of several substantial roadside buildings and enclosures, beginning in the 2nd century and continuing well into the 3rd century.

Excavators noticed a dramatic drop off in building quality after the Emperor Hadrian died in 138AD, about 16 years after his famous wall was built, suggesting the Empire’s commitment to holding the north of England weakened earlier than historians previously believed. The archaeologists concluded that Derventio started to decline seriously in the 200s until by 350AD the area was largely abandoned.

......

This is an extract from our book Secrets of the Crooked River, which is a kind of historical biography of the Northern Lakes and Cumbria, centred around the lovely town of Cockermouth.

You can pick up a copy, and of our latest book Secrets of the Lost Kingdom, from the New Bookshop on Main Street, Cockermouth. It is also available at the Moon and Sixpence, Lakeside, Keswick. You can get it at Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, along with Sam Read in Grasmere.

Or you can buy it instantly here: www.fletcherchristianbooks.com

Hello. My Name is Peter Skillen, and I would like to set the record straight on your well-written piece.

This site was discovered two days after the flood when I went into the field behind the Lakes Home Centre to investigate a van that was in the river. The first item I came across was a Roman altar, which was lying face down in the mud. As I walked towards the van, I discovered pottery sherds, Amphora handles and Samian ware. I then began to see the foundations of many buildings that were situated close to the river.

After I checked out the van to see if there were any occupants, I did a more careful search of the area and found many more items. I then went home to get my camera and Metre rule, which I used for scale. I took many photographs of the site, then reported my findings to Lancaster University. They sent out an archaeologist who confirmed that the site was indeed Roman and said there would be further investigations.

I have never been credited with finding this site and feel that it would not have been discovered had it not been for me finding it, as most of the site was covered over a few days later when soil from the towns cricket pitch was dumped and spread over the foundations and much of the pottery sherds.

I was a metal detectorist, but on this occasion was not metal detecting; I was simply checking to see if the van was occupied.

I still have the photographs if they are of any interest to anyone and they also prove that I did find this site.