How a beauty made and destroyed Cumbria’s greatest painter

Dalton-in-Furness’ George Romney transformed British fashion and culture with the aid of the 18th Century’s version of Marilyn Monroe.

She wears loose white drapery exposing her throat and chest. Her glossy hair is piled high and, as if whipped by the wind, loose strands trail over her bare shoulders. With her strikingly symmetrical oval face, pale skin and pink cheeks, she points an enchanting big-eyed look directly at the viewer. Her full mouth is open in a pronounced pout. Perhaps there is even a faint trace of perspiration on her décolletage because the artist kept his studio deliberately hot for such sittings.

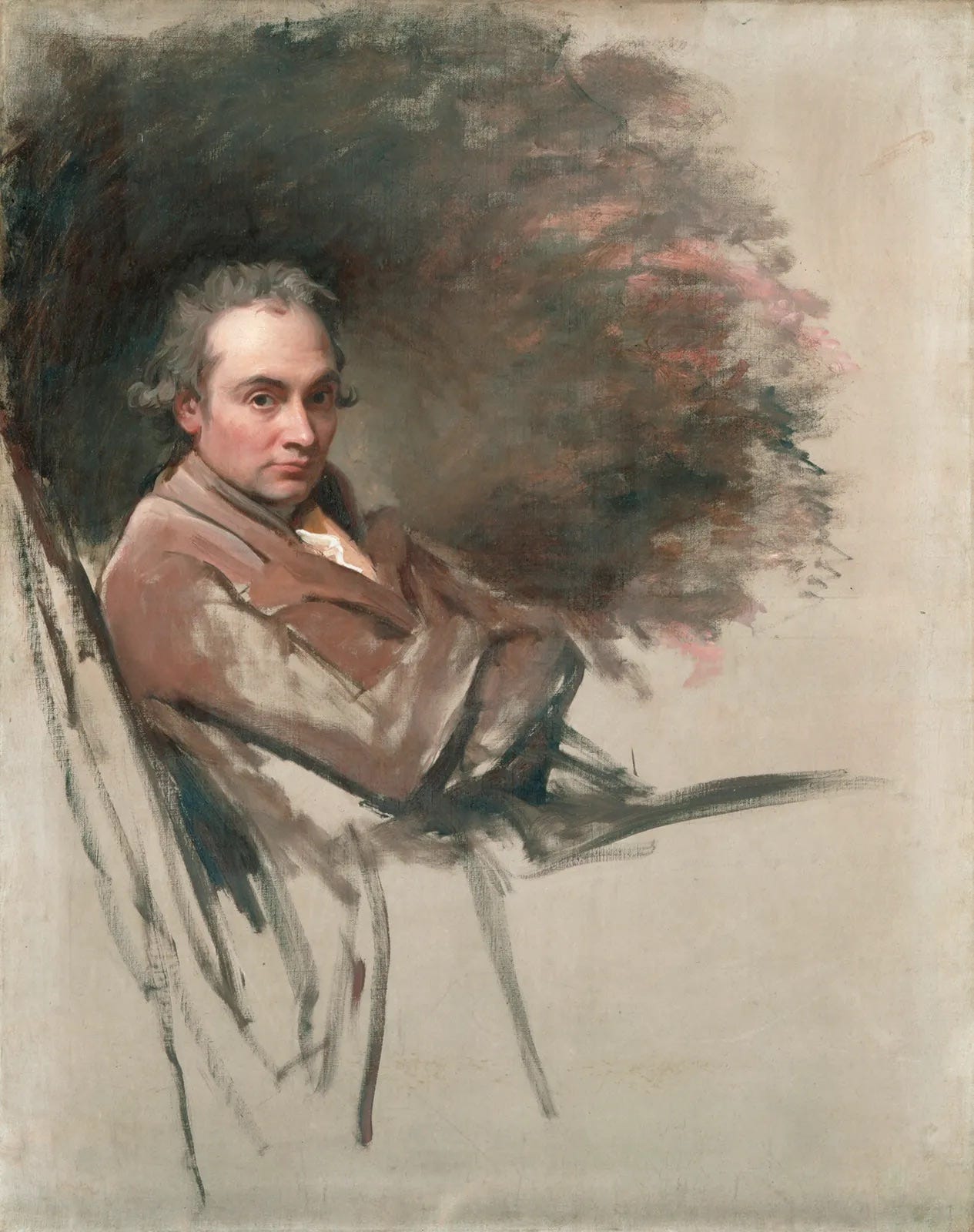

This extraordinarily fresh, immediate and accomplished oil sketch depicts the exuberant, sensual and vibrant seventeen-year-old Emma Hart. She is posing as the mythological sorceress Circe who had the power to enslave men and turn them into beasts. Painted in April 1792 by Cumbria’s greatest artist, George Romney, it marked the beginning of an ascent to a level of fame for both painter and model that seems breath-taking even today.

The beautiful image was in fact the product of a rather grubby money-making scheme. Emma at the time was the mistress of a hard-up MP, Charles Greville, who hoped he could sell pictures of the lovely woman to the landed gentry for a handsome price.

The story of the close connection between Romney, the son of a carpenter and cabinet maker from Dalton-in-Furness and the daughter of a Cheshire blacksmith who was baptised Amy Lyon, was controversial. It fostered a scandal that they were secret lovers and created a myth of the artist as a lonely, frustrated and infatuated Romantic genius. In fact Greville never complained or showed any sign that he suspected Romney of indiscretions.

But George was supposed to have struggled with depression induced by the eventual loss of a love who went on to become Lady Hamilton, the star of the European Grand Tour, pin-up of intellectuals and aristocrats, friend to monarchs and mistress to the ultimate patriotic hero, Admiral Horatio Nelson.

There was a kernel of truth to the stories, however. George was, like many artists, a profoundly melancholy personality, shy, easily wounded by criticism and unfairly portrayed in his lifetime as an unsociable curmudgeon. There is little doubt he loved Emma and suffered misery and mental turmoil later in life when he could not see her.

But he was also a brilliant, spontaneous draughtsman with superb technical ability whose mind teemed with ideas. He probably suffered from a bipolar condition in which victims periodically experience ecstatic highs and desperate lows in their mood lasting several weeks at a time.

That did not stop him becoming a key figure in British art. He has a claim to be considered the equal of Sir Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough as a portrait painter. He was also a deeply loyal, kind and generous man. His relationship with Emma was an unrequited passion on his side, based on her unavailability and his restraint.

On hers, there was a determination never to be pulled back into the world of high-class prostitution and a desire to be loved and protected. She thought achieving fame would be a guarantee of security. That was to prove an illusion.

Romney was, more than any other man, responsible for Emma’s rise from humble birth and sexual exploitation to fame and an exalted position in society, was He was, said his biographer, Sir Herbert Maxwell, “to his finger ends a true artist”.

The Cumbrian artist was a master practitioner in an era when paintings - and the cheap engraved copies of them - became the most potent form of mass media in a world before photography, television, movies and colour supplements.

He was as powerful an image maker as the greatest Hollywood directors, advertising agency moguls, magazine editors and haute couture designers are today.

The question that all this raises is: how on earth did Romney, an apparently badly-educated, low-class provincial, end up producing world-famous paintings that today sell for millions? George was born at Beckside in Dalton-in-Furness, Cumbria, in 1734, the third son of eleven children belonging to John Romney and Anne Simpson.

The boy was raised in a cottage named High Cocken in Barrow-in-Furness. He went to school in the tiny nearby village of Dendron. He appears to have been an indifferent student. His father took him out at the age of eleven and apprenticed him to the family business instead. Early biographers speculated that the family surname was originally “Romany” and that his ancestors must have come from the local gypsy population. George’s father was admired for his hard work and he earned the nickname “Honest John” because of his reputation for fair dealing. This was his downfall because he was a bad bookkeeper, negligent in collecting debts and he died a poor man.

John was occasionally employed as an architect and a designer of ornamental woodwork. His son took to decorating his fiddle with fancy carving. The boy copied engravings he saw in an illustrated monthly magazine his father took. He quickly developed a facility for drawing and acquired a copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s Treatise on Painting. Williams the local watchmaker encouraged his art, but perhaps also set a bad example by leaving his wife and setting up home with another woman.

Another cabinetmaker, Wright of Lancaster, admired the sketches George drew of his workmen, and suggested to John that he would do better apprenticed to an artist. It was very late to change professions: George was already twenty-one. Yet George found himself indentured to an itinerant portrait-painter named Christopher Steele who happened to be living in Kendal.

Steele was described by his enemies as having “the manners of a third-rate fop”. He had received some instruction in Paris from a successful Dutch master, Charles-André van Loo.

The Kendal townsfolk mockingly called the pretentious Steele “The Count”. Yet this flighty, improvident con artist gave Romney a solid technical grounding in the basics of painting from grinding colours to painting skin tones. This ensured Romney’s canvases have survived the ravages of time better than most of his rivals.

His works look much fresher today than umpteen faded portraits by Sir Joshua Reynolds who tried to give his work an instant old master look by mixing wax with oil paint to produce premature cracks and by counterfeiting translucent Leonardo-esque shadows with runny bitumen. Reynolds now had the technique he needed to conquer the richest art market in the world…18th Century London.

From the most improbable of provincial beginnings, Romney rose to become the most fashionable artist of his day. In partnership with his delightful sitter, he inspired a revolution in female fashion away from a nightmare of whalebone, stays and three-foot tall, powdered hair-dos towards simple and comfortable gowns inspired by Greek statues.

Emma chose sexy, revealing loose-fitting shifts with waistlines set just below the bosom. Her hairstyle, soon to be copied by nearly all ladies of fashion of the day, was also inspired by ancient sculptures, and even French women tossed out their massive wigs to achieve Lady Hamilton’s new look. Romney helped to popularise Hellenic ideas in the wake of excavations at Herculaneum and Pompeii which revealed day-to-day life in the classical world.

The sittings continued until 1785 when Greville found it necessary to dispense with the luxury of a mistress. The way he went about dumping her was cynical and repulsive. He introduced Emma to his uncle, fifty-five-year-old Sir William Hamilton, the British Ambassador to Naples, who was home on leave.

The older man was dazzled. “She is finer”, Sir William said “than anything to be found in antique art.” The following year Emma departed for Naples with Hamilton and her mother. She was frightened to leave Greville and only went on the basis that she was to get the best instruction on singing.

In many ways Emma Hart might be described as the Marilyn Monroe of the late 18th Century. She was just as vulnerable a personality as the film star. She became a fashion icon as a result of her collaboration with Romney, a sex symbol and, for a time, she embodied British national and cultural identity, not least as an unconventional diplomat. She moved at the very top of aristocratic society as the wife of Sir William Hamilton, British ambassador to the Kingdom of Naples.

There, she became popularly celebrated as an “ambassadress”, she was a success at court and she befriended the queen of Naples, the sister of Marie Antoinette. In Naples she used the knowledge of the classical myths she learned from Romney to create silent playlets she called “attitudes”.

Using her acting talent, her ability to convey profound emotion by a gesture and a few shawls she transfixed countless young men passing through Italian drawing rooms and gained international fame as a performer. At this time, Emma met and had a passionate, unapologetic affair with Nelson, which was the greatest scandal of the age.

By November that year, however, she was the acknowledged mistress of Sir William. Her absence from London deprived Romney of his chief source of inspiration and he fell into despair. “This cursed portrait painting!” He complained to Hayley. “How I am shackled with it!” He resolved to give it up, live frugally and concentrate on his grandiose paintings based on scenes in Shakespeare’s plays. His previous admirers were appalled.

When Lord Chancellor Edward Thurlow heard Romney was at work on The Tempest, he thundered: “What is Romney at work for it? He cannot paint in that style. By God! He’ll make a balderdash business of it.” By 1791, signs emerged that Romney’s physical and intellectual powers were in decline.

He was only fifty-seven and his ability to produce fine portraits was unaffected for many years after this. But he plunged more frequently into hopeless depressive moods and began to obsess about extravagant schemes. It appeared Romney’s artistic life was over.

This is an extract taken from my book called The Lost Kingdom. You can buy the book at The New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, at the Moon & Sixpence cafe at Lakeside, Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle, and Sam Read in Grasmere.