Hanged in chains: Henry VIII takes revenge on Cumbria

Protesters suspended in body-shaped iron cages after 40,000 northerners joined “loyal rebellion” that almost toppled the king

It was a night when the grieving women of Cumberland came face to face with the horrible consequences of Henry VIII's wrath.

Stealthily, and at dreadful risk to their own lives, a crowd of widows, mothers and neighbours crept silently into the Market Place to recover the bodies of five local men executed for rebelling against the King.

The weeping mourners hauled down the strange body-shaped iron cages in which the Earl of Cumberland's men had left the dead to rot two months before

'The west parts, from Plumbland to Muncaster, is all a flutter'.

With the help of a blacksmith they hammered them open. Under cover darkness, groups of women removed the five stinking, putrefying, skeletal corpses of their loved ones from the chains that bound them.

They laid the bodies gently down in shrouds smelling of sweet herbs. Then they carried the dead, all poor farm hands and town artisans (the bailiff of Embleton was the highest man among the deceased) swiftly up the hill.

There they secretly buried the cadavers beside the beautiful gothic church endowed by Henry “Hotspur” Percy. One or two of the relatives were later to die from the "corruption" picked up from the bodies they had cut down.

It was the end of the most serious armed rebellion Henry VIII ever faced - and Cockermouth was at its epicentre in Cumberland.

"Strike off his head!" and "Stick (kill) him!"

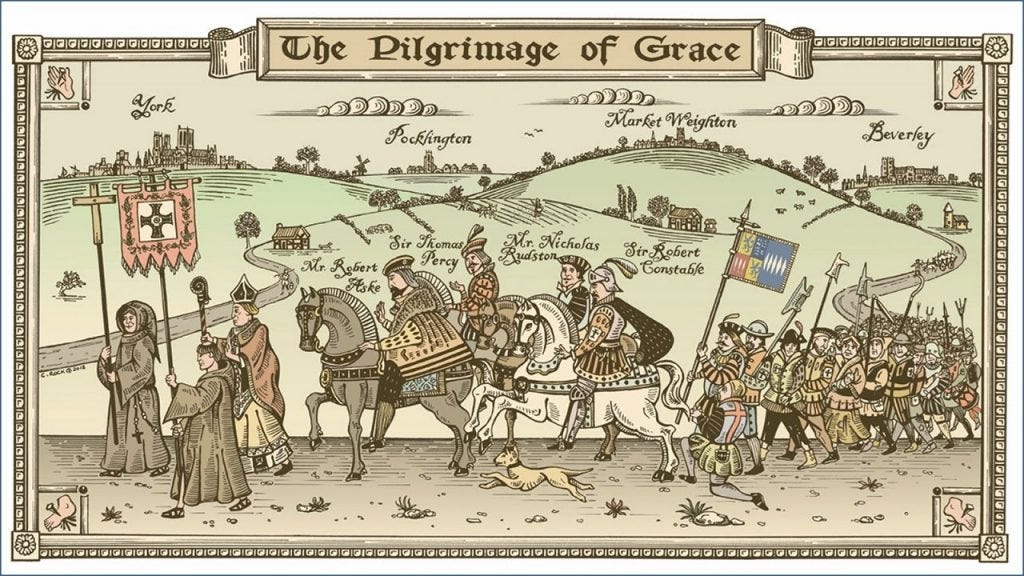

It was a massive, spontaneous protest that drew enormous support among the lower classes, artisans and many gentry across the north of England. It was known as the "Pilgrimage of Grace for the Commonwealth."

The uprising started in October 1536. This outpouring of anger came close to bringing the Tudor regime down. At its peak the revolt saw a rebel army of 40,000 men rampage across the north. The king had no answer. He could only muster a force of 12,000 mercenaries to defend his side of the argument. A charismatic and high-minded London lawyer called Robert Aske led the Pilgrims.

They were protesting against Henry's decision to break with the Roman Catholic Church. Henry, desperate for an heir, was furious after the Pope refused to annul his marriage to Catharine of Aragon so that he could marry Anne Boleyn. So he made himself head of a Church of England.

Touchingly, the dissidents truly believed they were merely mounting a "loyal rebellion." They were convinced that the King was unaware of his regime’s oppressive policies that they blamed on Henry's chief minister, Thomas Cromwell.

English people were very religious 500 years ago. They believed quite literally in the existence of heavenly bliss and the tortures of Hell. Life in Tudor times was insecure and death was never very far away. So the hope of everlasting bliss was a vital consolation for a tough life. For this reason, people feared eternal damnation more than death itself.

Kings and Popes, and to a great extent ordinary people, believed that extreme punishments for rebels were justified for those who challenged this Divine Order. Henry was no shrinking violet when it came to judicial murder. He had 72,000 people put to death during his reign.

So his general, the Duke of Norfolk, knew something special was required when the King demanded "dreadful execution" be done on the inhabitants of every town, village, and hamlet, that took part in the rebellion.

The King demanded a "fearful spectacle" to deter any future revolt. In particular, the King specified that the leading rebels be hung in chains.

By having the five Cockermouth men executed by this method, Henry was playing a mind game on the families. Common people took seriously the Bible's commandment that one should bury the deceased immediately.

Without a proper burial, the victim's soul would remain in turmoil. As we shall see, hanging in chains specifically ruled out a Christian burial. In the minds of the bereaved, the King was taking revenge by obliterating his enemies' chance of everlasting life.

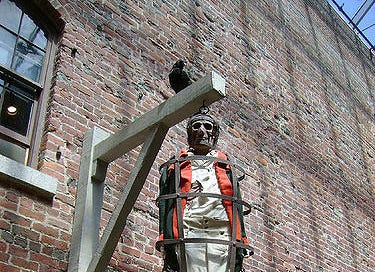

Being hung in chains (pedants use the word “hanged”) meant 30 minutes on the end of a rope, then your corpse being forced into a body-shaped iron cage, being wrapped in chains then suspended on a swivel in public. Bodies were sometimes coated in tar so they took longer to rot.

Then the bones would be scattered randomly on unconsecrated ground. It was an expensive punishment. One prisoner hung in chains cost the Tudor state £67, about £38,000 in today's money.

The savage retribution Henry imposed on the Cockermouth culprits illustrates his paranoia. Courtiers said the Pilgrimage of Grace started Henry VIII's slide from being a intelligent, charismatic, fatherly and joyful young prince into the dour, irritable, mistrustful, cruel and enraged tyrant of his later years.

For him, 1536 had already been a terrible year. It was his "annus horribilis." He had received the jousting injury to his leg that would eventually kill him. The Pope excommunicated him, potentially licensing France and Spain to invade England. His wife Anne Boleyn first miscarried the boy child the King wanted and was then "discovered" to have committed adultery with a number of men (an allegation Henry apparently believed).

Anne was executed and her daughter Elizabeth joined Mary in being declared bastards, leaving Henry with no legitimate heir. This was compounded by the death at 17 of Henry's illegitimate but much-loved son Henry Fitzroy, depriving the king even of the option of legitimising his favourite offspring. In July 1536, Henry responded to these calamities by ordering his first minister Cromwell, to start dissolving the monasteries. This is what triggered the massive armed rebellion.

The King's front man for these policies in Cumbria was Sheriff Henry Clifford, the Earl of Cumberland, the "hardest landowner in the north." Enemies called him "an avaricious man who put profit before the principles of good lordship."

Ordinary Cumbrians were particularly angry about the increases in "gressums" - cash paid to the Lord at the start of a tenancy - which hit the poorest running "penny farms" and those relying on newly enclosed commons.

In January 1537 Henry loyalist Sir Thomas Curwen of Workington wrote that 'The west parts, from Plumbland to Muncaster, is all a flutter'. He added that on the 13th of that month a servant of Sir Thomas Leigh, one of Henry VIIIs key agents, was seized by thousands of protesters as he arrived in Muncaster and carried to Egremont and then to Cockermouth. A great crowd filled the Market Place, crying: "Strike off his head!" and "Stick (kill) him!"

Clifford, not the brightest of the Royal loyalists, explained in a letter to Cromwell, clearly if clumsily, that Cumbrians hated him so much they were killing anyone suspected of supporting him: "The commons in every quarter throughout this country are so wilfully minded against you, in case any man should have chanced to have been taken therewith, he would have died without help; as yet they continue in the same fury against you, so that in case any man speak of you, he is despised of all the country."

This letter gave Cromwell every reason to encourage an already vengeful Henry to crack down savagely.

———-

This is an extract from our book, Huge & Mighty Forms, which investigates why Cumbria, the least populated county in England, has produced so many remarkable people.

You can buy a copy at the New Bookshop on Main Street, Cockermouth, the Moon & Sixpence coffee house on Lakeside, Keswick, or Bookends, Main Street, Keswick. It is also available from Bookends, Castle Street, Carlisle and Sam Read, Grasmere.

Alternatively, you can buy it instantly here now: www.fletcherchristianbooks.com

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Hidden Cumbrian Histories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.