Daffodils, lonely clouds and tragic Dora Wordsworth

How William Wordsworth's narcissism stopped his favourite daughter achieving happiness until it was almost too late.

Deep in the Lake District lies a patch of woodland that is animated every spring with fluttering and dancing daffodils.

It is known as Dora’s field. But the happy display that greets visitors heading to William Wordsworth’s former homes nearby at Dove Cottage and Rydal Mount hides an awful story.

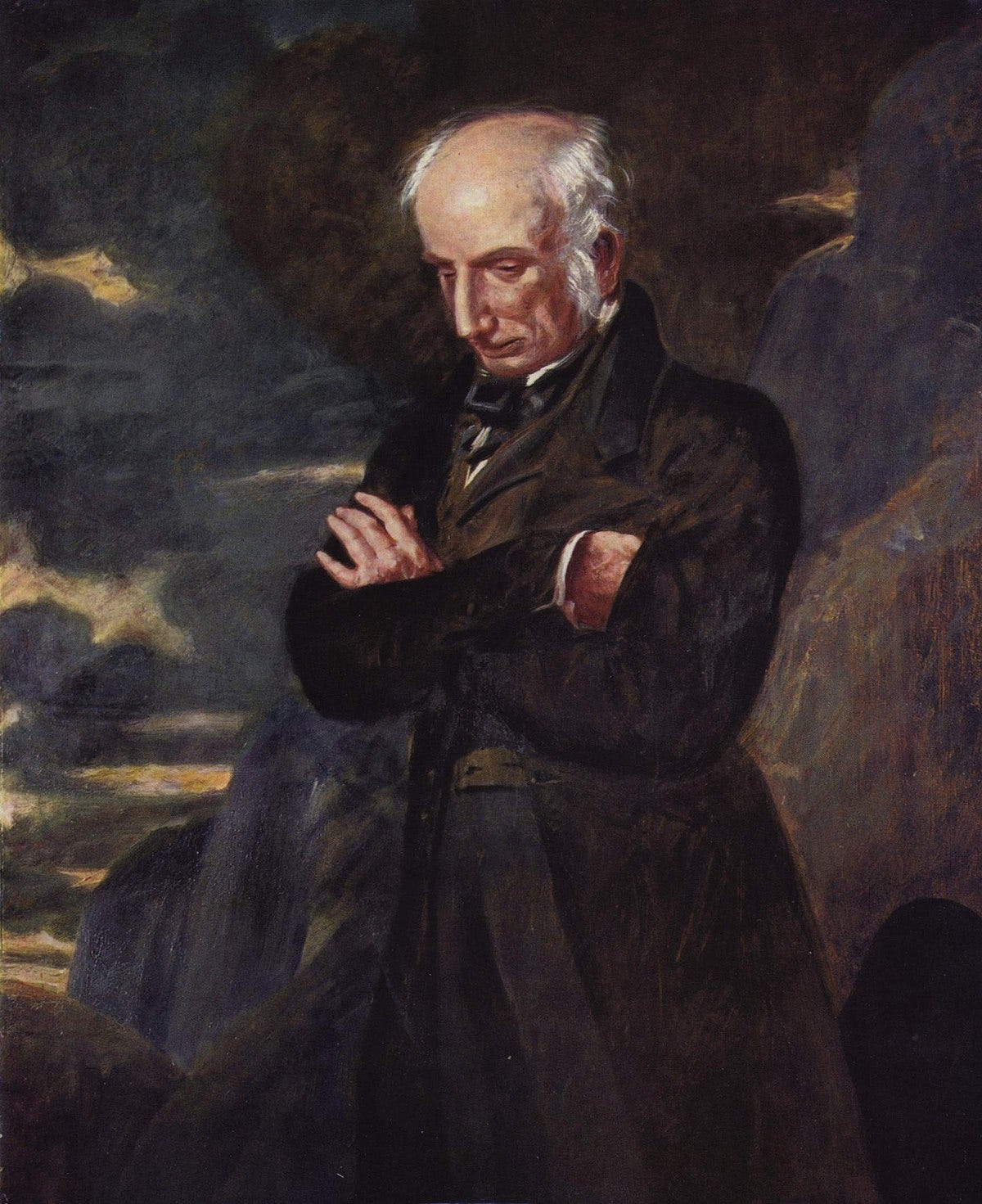

For the man who planted the flowers, arguably the greatest English poet after Shakespeare, did so in an agony of tormented mourning over her early death. Perhaps by pushing the bulbs into the damp earth he unconsciously acknowledged a sense of guilt - that his narcissistic need to bind his favourite child to himself had kept her from the man she loved until it was tragically late.

Numberless biographies present the Wordsworth family’s residence at Dove Cottage between 1799 and 1808 as a peaceful, creative idyll. It is true that William wrote most of his best-loved poetry there. His sister Dorothy also kept her famous Grasmere Journals during those years — four small notebooks that detail her relationship with William and their adventures in the Lake District with friend and fellow poet Samuel Coleridge. Wordsworth quarried her vivid observations as material for his poems.

But the tiny former public house they lived in was cold, damp and uncomfortable. Family members paid a heavy price in stress, illness and, ultimately, mental breakdown as the poet demanded their constant devotion to his needs. William and his unassuming wife Mary had five children, John, Dora, Thomas, Catherine (who may have suffered Down's Syndrome) and Willie. Catherine died at three years old and Thomas died aged six only six months later.

The eldest, John, was into hunting and fishing. He was not intellectual but Wordsworth demanded he follow in his father’s footsteps and so John suffered the torment of tutors.

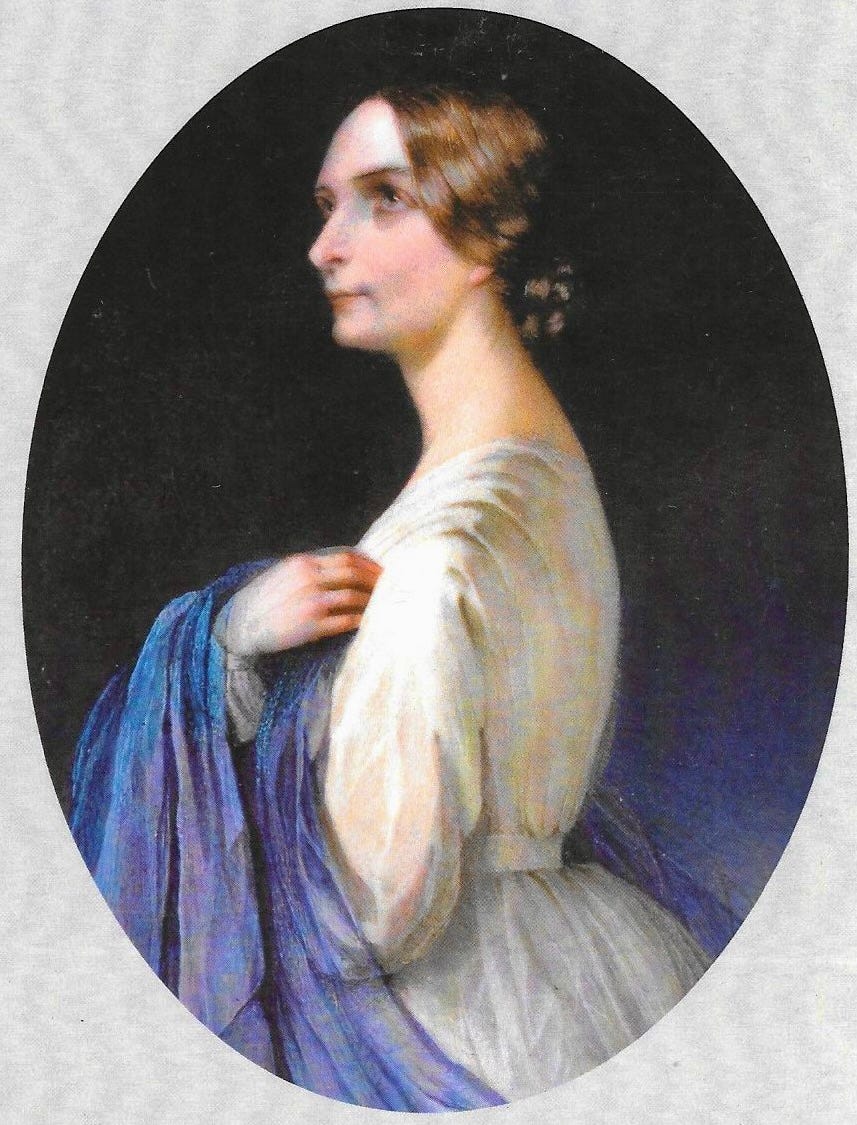

Dora, born 1804, was the only surviving daughter. She was named after Dorothy and she showed the same intellectual prowess as her aunt. Wordsworth became obsessed with Dora. He worried constantly that he might lose her as well. His anxiety is revealed in a dream-like 1822 sonnet. It begins: “I saw the figure of a lovely maid…for she was one I loved exceedingly”. But then he imagines her “heavenly features” dissolving into a mist and “melting into air.”

William doted on Dora, and relied heavily on her as she grew older, especially in later life when his eyesight began to fail in the 1820s. She often assisted him with proofreading and other tasks relating to his works. Wordsworth was extremely jealous of anyone who threatened what seemed, from his point of view, the perfect familial and working relationship.

But as William’s emotional bond with Dora grew in intensity, Dorothy became very jealous. Dora was “very pretty, very kittenish, very quick, very clever,” Dorothy wrote when Dora was young. “Most people think Dorothy far cleverer than John - but that's a mistake. She is proud and not unwilling to display what she can do,” Dorothy added that Dora had to be imprisoned regularly as a child in order to punish her. Dove cottage was a cauldron of emotion.

Dora's wit and forwardness undermined her brother's confidence at the local village school so they decided she had to be removed to a boarding school in Appleby.

The deaths of Dora's two siblings happened while she was there. But when she was brought back she was not given any comfort or explanation of what had happened to them. An irritated Wordsworth wrote how, as he departed from visit to Appleby school, Dora had clung to his trousers, weeping. The Wordsworth remedy was to visit Dora less.

Sent to another boarding school in Ambleside, within easy walking distance of Dove Cottage, she was still not allowed to come home at weekends. Dora probably contracted tuberculosis at this school and her weight plummeted at one point with anorexia nervosa.

Yet Dora grew into a beautiful and intelligent woman. She became acquainted with a man called Edward Quillinan. He was a neighbour of the Wordsworths, a translator of Portuguese poetry who lived with his wife Jemima at Loughrigg Holme. This was next door to Rydal Mount where the Wordsworth family had moved in 1813 as tenants of Lady Anne le Flemming of Rydal Hall.

In 1825 Lady Flemming announced her intention to evict the Wordsworths and hand the tenancy to a relative. Wordsworth, desperate not to be expelled from picturesque Rydal, retaliated. As a defence strategy he bought the little plot of land from the Backhouse family in 1826. Then he threatened to build on it. He even paid George Webster, a famous Kendal architect, to draw up a design that would spoil Lady Anne’s view if she went ahead with her plan to chuck him out of Rydal Mount.

In the end this contingency plan was not needed as Lady Flemming withdrew the threat. The Wordsworth family retained the field and it was eventually pledged to Dora as a future inheritance.

In time, William evolved from being a French Revolution supporting hippy to an authoritarian Victorian patriarch. The intensely selfish character of Wordsworth’s genius was famous – indeed notorious – in literary circles. In conversation with other writers such as William Hazlitt he frequently gave the impression that he thought himself superior to Shakespeare and Milton.

The younger generation of poets marvelled at his self-centredness. The left wing John Keats trailed up to Cumberland to meet his idol only to find Wordsworth was, to his horror, absent organising a Tory election campaign. The younger man coined the highly ambivalent term “egotistical sublime” to describe Wordsworth’s poetry.

Narcissists like Wordsworth need others to be who they want them to be, rather than who they actually are, and this included his children. After Quillinan’s wife Jemima died of burns when her nightdress caught fire Dora’s fondness for the deeply depressed Quillinan grew. In response, Wordsworth did everything he could to isolate his child from her would-be spouse.

Dora became a surrogate mother to Edward’s children. They wrote letters to each other. He was her “very silly Mr Quilly.” As Dora's crush on Quillinan blossomed into love and the widower became entranced with her, Wordsworth's anger exploded at the seeming defiance of his daughter. He regarded Dora as his full-time amanuensis, vital for laboriously copying out and checking his manuscripts - work Dorothy was by now too frail to cope with.

He dismissed the relationship, decreeing that Dora should devote her life to looking after him. William's decades-long tyranny and closeting of Dora had already had a grave impact. She never fully grew up. Coleridge's son Hartley Coleridge called her “a child woman.”

Edward was considerably older than Dora and not financially secure. Wordsworth was adamant that there was to be no question of a relationship, so for years they tried to conceal their courtship was in letters and clandestine meetings.

Eventually, Wordsworth tried to crush Dora's relationship with Quillinan altogether. He had no money and he didn't have a job, Wordsworth objected. (In fact, Quillinan was just like William and Dorothy had been a few years before). Dora was by then thirty-seven, ancient in terms of the Victorian marriage market.

She was instinctively loyal to her parents. So it was a tug of war. Even Dorothy, writing in one of her lucid moments, said the couple should be allowed to marry “before all the life and light is gone.”

The couple wished to marry but Dora feared her father. “I feel as if I could never be a blessing to your home unless I took with me my parent’s blessing sealed with a kiss”, wrote Dora in a letter to Edward.

A mutual friend to all parties, Isabella Fenwick, who had been close to William, acted as mediator between the distraught poet and his upset daughter. With Wordsworth’s very grudging consent, Edward and Dora became engaged at the end of 1838. The poet declared Dora was "acting as she has chosen to do with my strongest disapprobation" and refused to attend the wedding if it was held in the Lake District.

Disgusted by William's obduracy and snobbishness, Isabella and William’s younger brother Christopher Wordsworth settled money on Dora. They arranged for her to marry Quillinan on neutral ground, Isabella’s house in Bath. Even then, they feared the poet would try to disrupt proceedings.

“I do sincerely trust that nothing will interfere with (the marriage) taking place on that day. Mr Wordsworth behaves beautifully,” said Isabella in a letter to Henry Taylor on 6 May 1841.

It has been wrongly reported that Wordsworth relented and attended Dora’s wedding. He did not. Although he was in Bath on 11 May, he couldn’t bear to witness his daughter’s marriage and so remained at the lodging house.

Dora, increasingly emaciated and weakened by anorexia and TB, held out hope that her father would change his mind and come to support her. But he failed to appear at the porch of St James’ church. Deeply distressed by his absence, Dora stumbled unsteadily down the aisle to be given away instead by her brother Willy. She looked ashen-faced and swayed during the service as if about to faint.

It appears Wordsworth deigned to appear later at the wedding breakfast. But he compounded the offence by refusing to hand over what was always supposed to be the bride’s dowry - Dora's Field, the plot of land near Rydal Mount.

Dora and Edward immediately escaped to Portugal and in the sun she enjoyed enough health to write a slightly fictional but vivid book “A Journal of a Few Months Residence in Portugal.”

Extending his stay in Bath, Wordsworth was commissioned by Cambridge University to write an ode celebrating the installation of Prince Albert as chancellor. But he was unable to complete it because he was suddenly summoned back to Cumbria to receive bad news.

Edward informed them that Dora was gravely ill with tuberculosis. The Wordsworths spent the final few weeks of Dora’s life by her side. On 9 July 1847 Dora Quillinan, née Wordsworth, writer and muse, died at the age of 42.

In that field near to the family home at Rydal Mount – now owned by The National Trust – Wordsworth, his wife and his gardener planted hundreds of daffodil bulbs in her memory.

Today, Wordsworth’s daffodils have become a poetic cliche. The famous poem “I wandered Lonely as a Cloud” which William composed in 1804 is ridiculed as slightly whimsical piece of trivia. But it was anything but for Wordsworth. The daffodils which “flash upon that inward eye” symbolise the power of memory to recreate intense emotion in the mind while the poet is at home lying on his couch recollecting experience in tranquility.

He was devastated by his memory of Dora and all he had lost. From the moment of her death, Wordsworth lost the power to compose poetry. He died three years later.

He is buried at St Oswald’s Church, Grasmere, next to his daughter.

There is more about Dora, Dorothy, Mary and William in my book Huge & Mighty Forms which you can buy here.

If you are in Cumbria now, my books are available at the New Bookshop, Main Street, Cockermouth, the Moon & Sixpence cafe at Lakeside, Keswick, Bookends in Keswick and Carlisle and Sam Read in Grasmere.